1814-1840 Chapter II FLORIDA AND THE MONROE DOCTRINE

CHAPTER II.

FLORIDA AND THE MONROE DOCTRINE

It was a delicate question after the Louisiana purchase how much territory it embraced east of the Mississippi. Louisiana had under France, till 1762, reached the Perdido, Florida's western boundary at present, and was "retroceded" by Spain to France in 1800 "with the same extent that it had when France possessed it." The United States of course succeeded to whatever France thus recovered. Spain claimed still to own West Florida, the name given by Great Britain on receiving it from France in 1763 to the part of Louisiana between the Perdido and the Mississippi. Spain had never acquired the district from France, but obtained it by conquest from Great Britain during our Revolution.

This claim by Spain, based only on the "retro" in the treaty of 1800, our Government viewed as fanciful, regarding West Florida undoubtedly ours through the Louisiana purchase. Spain was intractable, first of herself, later still more so through Napoleon's dictation. Hence our offer, in Jefferson's time, to avoid war, of a lump sum for the two Floridas was spurned by her. In 1810 and 1811, to save it from anarchy--also to save it from Great Britain or France, now in the whitest heat of their contest for Spain--we occupied West Florida, as certainly entitled to it against those powers, yet with no view of precluding further negotiations with Spain. When in 1812 Louisiana became a State, its eastern boundary ran as now, including a goodly portion of the region in debate.

The necessity of acquiring East Florida, too, was more and more apparent. That country was without rule, full of filibusterers, privateers, hostile refugee Creeks and runaway negroes, of whose services the English had availed themselves freely during the war of 1812, when Spaniards and English made Florida a perpetual base for hostile raids into our territory.

A fort then built by the English on the Appalachicola and left intact at the peace with some arms and ammunition, had been occupied by the negroes, who, from this retreat, menaced the peace beyond the line. Spain could not preserve law and order here. This was perhaps a sufficient excuse for the act of General Gaines in crossing into Florida and bombarding the negro fort, July 27, 1816. Amelia Island, on the Florida coast, a nest of lawless men from every nation, was in 1817 also seized by the United States with the same propriety. Knowledge that Spain resented these acts encouraged the Floridians. Collisions continually occurred all along the line, finally growing into general hostility. Such was the origin of the First Seminole War.

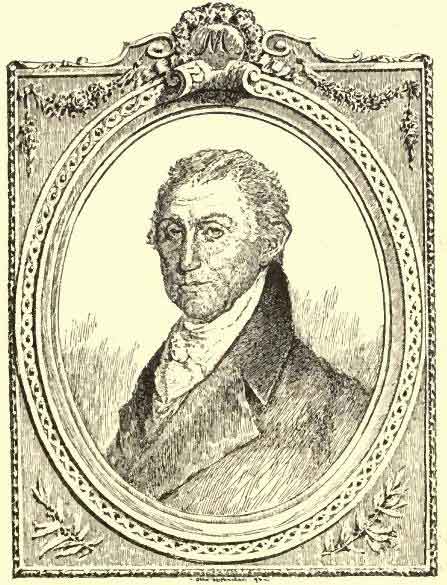

James Monroe.

From a painting by Gilbert Stuart--now the property of T. Jefferson Coolidge.

December, 1817, Jackson was placed in command in Georgia. To clear out the filibusterers, the chief source of the Indians' discontent ever since before the Creek War, the hero of New Orleans, mistakenly supposing himself to be fortified by his Government's concurrence, boldly took forcible possession of all East Florida. Ambrister and Arbuthnot, two officious English subjects found there, he put to death.

This procedure was quite characteristic of Old Hickory. He acted upon the theory that by the law of nations any citizen of one land making war upon another land, the two being at peace, becomes an outlaw. International law has no such doctrine, and most likely the maxim occurred to Jackson rather as an excuse after the act than in the way of forethought. Nor was it ever proved that the two victims were guilty as Jackson alleged. With him this probably made little difference. Having undertaken to quiet the Floridian outbreaks he was determined to accomplish his end, whatever the consequences of some of his means.

With the country the New Orleans victor, who had now dared to hang a British subject, was ten times a hero, but the deed confused and troubled Monroe's cabinet not a little. Calhoun wished General Jackson censured, while all his cabinet colleagues disapproved his high-handed acts and stood ready to disavow them with reparation. On this occasion Jackson owed much to one whom he subsequently hated and denounced, viz., Quincy Adams, by whose bold and acute defence of his doubtful doings, managed with a fineness of argument and diplomacy which no then American but Adams could command, he was formally vindicated before both his own Government and the Governments of England and Spain.

The posts seized had of course to be given up, yet our bold invasion had rendered Spain willing at last to sell Florida, while Great Britain, wishing our countenance in her opposition to the anti-progressive, misnamed Holy Alliance of continental monarchs, concurred. Spain after all got the better of the bargain, as we surrendered all claim to Texas, which the Louisiana purchase had really made ours.

The Florida imbroglio nursed to its first public utterance a sentiment which has ever since been spontaneously taken as a principle of American public policy, almost as if it were a part of our law itself. Spain's American dependencies had been sensible enough to avail themselves of that land's distraction in Napoleon's time, to set up as states on their own account. She naturally wanted them back. Ferdinand VII. withheld till 1820 his signature of the treaty ceding Florida, in order to prevent--which, after all, it did not--our recognition of these revolted provinces as independent nations. Backed by the powerful Austrian minister, Metternich, and by the Holy Alliance, France, having aided Ferdinand to suppress at home the liberal rebellion of 1820-23, began to moot plans for subduing the new Spanish-American States. Great Britain opposed this, out of motives partly commercial, partly philanthropic, partly relating to international law, yet was unwilling so early to recognize the independence of those nations as the United States had done.

VOL. IIl.--4

50 WHIGS AND DEMOCRATS

Assured at least of England's moral support, President Monroe in his message of December, 1823, declared that we should consider any attempt on the part of the allied monarchs "to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety," and any interposition by them to oppress the young republics or to control their destiny, "as a manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States." This, in kernel, is the first part of Monroe's doctrine.

The second part added: "The American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers." The meaning of this was that the mere hap of first occupancy on the continent by the citizens of any country would not any longer be recognized by us as giving that country a title to the spot occupied.

These important doctrines--for though akin in principle they are really two--were no sudden creation of individual thought, but the result rather of slow processes in the public mind. Germs of the first are traceable to Washington; express statements of both, yet not essentially detracting from Monroe's originality, to Jefferson. Both were put in form by Quincy Adams, Monroe's Secretary of State. Especially Monroe's, we believe, is the second, a resolution to which Russia's advance down the Pacific coast, and more still the recent vexations from the proximity of Spain in Florida, had pushed him.