1814-1840 Chapter IV THE GREAT NULLIFICATION

CHAPTER IV.

THE GREAT NULLIFICATION

The tariff rates of 1816 on cottons and woollens were to be twenty-five per cent. for three years, after that twenty. Instead of this the cotton tariff was in 1824 replaced at twenty-five per cent., the same as that upon woollens costing thirty-three and a third cents or less per square yard; woollens over this price bearing thirty per cent. Wool, which by the tariff of 1816 was free, now bore, some grades fifteen, some twenty, some thirty per cent. Iron duties were put up in 1818 and again in 1824, from which date for ten years they ranged between forty and one hundred per cent. The whole tendency of tariff rates was strongly upward. The duty upon all dutiables averaged between 1816 and 1824 only twenty-four and a half per cent; from 1824 to 1828 the average was thirty-two and a half per cent. Importation remained copious, notwithstanding, which made the cry for protection louder than ever.

From Quincy Adams's presidency the tariff question becomes on the one hand political, dividing Whigs from Democrats about exactly, which had never been the case before, and on the other, sectional, the West, the Centre, and now also the East, pitted against the solid South, except Louisiana. The year 1824 heard Webster's last speech for free trade and saw Calhoun's and Jackson's last vote for protection. However, so strong was the protectionist sentiment in the XXth Congress, though democratic, that free-traders could hope to defeat the new tariff bill of 1828 only by rendering it odious to New England. They therefore conspired to make prohibitive its rates for Smyrna wool, and nearly so those on iron, hemp, and cordage for ship-building; also on molasses, the raw material for rum, whereon no drawback was longer to be allowed if it was exported.

John Quincy Adams.

From a picture by Gilbert Stuart.

The Whigs had arranged, to be now passed, a series of minimum rates on woollens, by which all costing over fifty cents a square yard were to pay as if costing $2.50, and all over this as if costing $4.00. The rate was to be forty per cent. the first year, forty-five the second, and fifty thereafter.

This illustrates the famous "minimum principle," which has played such a figure in all our tariff history since 1816, its effect being always to make the tariff much higher than it seems. Thus in the case before us, most of the woollens then imported cost about ninety cents. If based on this price, the tariff would be thirty-six per cent., but if based on $2.50 as the price, it would mount up to one hundred and ten per cent. To prevent this and to render the bill still more unpalatable to the Whigs, the Democrats introduced a dollar "minimum," so that the tariff on the bulk of our imported woollens, costing, as just stated, about ninety cents, would come in at forty-four and four-tenths per cent.

But as this was after all more vigorous protection than woollens had before received, amounting, through minima, in some cases to over one hundred per cent., sixteen out of the thirty-nine New England members, led by Webster, accepted this universally odious tariff bill--the Tariff of Abominations, it was called--as the preferable evil, and, aided by a few Democrats in each house, made it a law. The average duty on dutiables was now about forty-three and a third per cent.

No one can question that this high tariff worked injustice to the South. It forced from her an undue share of the national taxes, as well as extensive tribute to northern manufacturers. But in resenting the evil she exaggerated it, mistakenly referring all the relative decrease in her prosperity to tariff legislation, when a great part of it was due simply to slavery. The South complained that selfishness and political ambition, not patriotism or reason, determined the dominant policy, and there was of course some truth in this.

Moreover, as New England now favored it, this policy bade fair to become permanent, and since the tariff bills did not announce protection as their purpose, the constitutionality of them could not be gotten before the courts.

Nearly all the southern Legislatures consequently denounced the tariff as unjust and as hostile to our fundamental law. Most of them were, however, prudent enough to suggest no illegal remedies. Not so with fiery South Carolina, where a large party, inspired by Calhoun, proposed a bold nullification of the tariff act, virtually amounting to secession. At a dinner in this interest at Washington, April 13, 1830, Calhoun offered the toast: "The Union; next to our liberty the most dear; only to be preserved by respecting the rights of the States."

John C. Calhoun was now, except, perhaps, Clay, the ablest and most influential politician in all the South. Born in South Carolina in 1782, of Irish-Presbyterian parentage, though poor and in youth ill-educated like Clay and Jackson, his energy carried him through Yale College, and through a course of legal study at Litchfield, Conn., where stood the only law school then in America. November, 1811, found him a member of Congress, on fire for war with Britain. Monroe's Secretary of War for seven years from 1817, he was in 1825 elected Vice-President, and reelected in 1828. He had meantime turned an ardent free-trader, and seeing the North's predominance in the Union steadily increasing, had built up a nullification theory based upon that of the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions and the Hartford Convention, and upon the history of the formation of our Constitution. He had worked out to his own satisfaction the untenable view that each State had the right, not in the way of revolution but under the Constitution itself--as a contract between parties that had no superior referee--to veto national laws upon its own judgment of their unconstitutionality.

John C. Calhoun

From a picture by King at the Corcoran Art Gallery.

On this doctrine South Carolina presently proceeded to act. November 24, 1832, the convention of that State passed its nullification ordinance, declaring the tariff acts of 1828 and 1832 "null, void, and no law," defying Congress to execute them there, and agreeing, upon the first use of force for this purpose, to form a separate government.

This was the quintessence of folly even had good theory been behind it. The tone of the proceeding was too hasty and peremptory. The decided turn of public opinion and of congressional action in favor of large reduction in duties was ignored. But the theory appealed to was clearly wrong, and along with its advocates was sure to be reprobated by the nation. A precious opportunity effectively to redress the evil complained of was wantonly thrown away. Worst of all, from a tactical point of view, South Carolina had miscalculated the spirit of President Jackson. At the dinner referred to, his toast had been the memorable words:

"Our Federal Union; it must be preserved." Men now saw that Old Hickory was in earnest. General Scott, with troops and warships, was ordered to Charleston.

The nullifiers receded, a course made easier by Clay's "compromise tariff" of 1833, gradually reducing duties for the next ten years, and enlarging the free list. From all duties of over twenty per cent. by the act of 1832, one-tenth of the excess was to be stricken off on September 30, 1835, and another tenth every other year till 1841. Then one-half the excess remaining was to fall, and in 1842 the rest, so that the end of the last named year should find no duty over twenty per cent.

This episode, threatening as it was for a time, drew in its train results the most happy, revealing with unprecedented vividness to most, both the original nature of the Constitution as not a compact, and also the might which national sentiment had attained since the War of 1812. The doctrine of state rights was seen to have gradually lost, over the greater part of the country, all its old vitality. Nearly every State Legislature condemned the South Carolina pretensions, Democrats as hearty in this as Whigs.

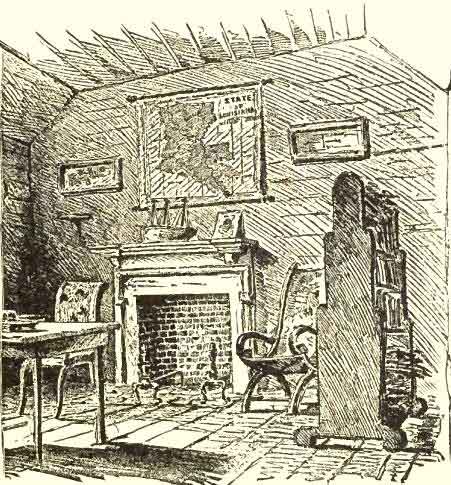

Calhoun's Library and Office.

Jackson's proclamation against them--impressive and unanswerable --ran thus: "The Constitution of the United States forms a government, not a league; and whether it be formed by compact between the States, or in any other manner, its character is the same . . . . . I consider the power to annul a law of the United States incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed. . . . Our Constitution does not contain the absurdity of giving power to make laws, and another power to resist them. To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say that the United States are not a nation."

The congressional debates which the nullification question evoked, among the ablest in our parliamentary history, held the like high national tenor. Calhoun's idea, though advocated by him with consummate skill, was shown to be wholly chimerical. The doughty South Carolinian, from this moment a waning force in American politics, was supported by Hayne almost alone, the arguments of both melting into air before Webster's masterful handling of constitutional history and law.

THE GREAT NULLIFICATION 77

Not questioning the right of revolution, admitting the general government to be one of "strictly limited," even of "enumerated, specified, and particularized powers," the Massachusetts orator made it convincingly apparent that the Calhoun programme could lead to nothing but anarchy. It was seen that general and state governments emanate from the people with equal immediacy, and that the language of the clause, "the Constitution and the laws of the United States made in pursuance thereof" are "the supreme law of the land, anything in the constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding," means precisely what it says. To this language little attention had apparently been paid till this time.