The Chickamauga Rule

By COL Richard D. Hooker Jr.

U.S. Army retired

The colonel looked around the hangar impassively. "Men, have you ever heard about the Chickamauga Rule?" The commanders and staff looked at each other, puzzled. InU.S. Army retired

the fall of 1995, we were all tired, having worked overtime for weeks preparing to deploy. Our Italy-based paratroop battalion was closed on the departure airfield, and soon we would

journey to an other foreign land for another challenging mission. We were nervous. The whole world was watching this time. We would be the first American unit in, and the media were

all over us. In fact, they were flying in on the same planes as we were. What on earth was the colonel talking about?

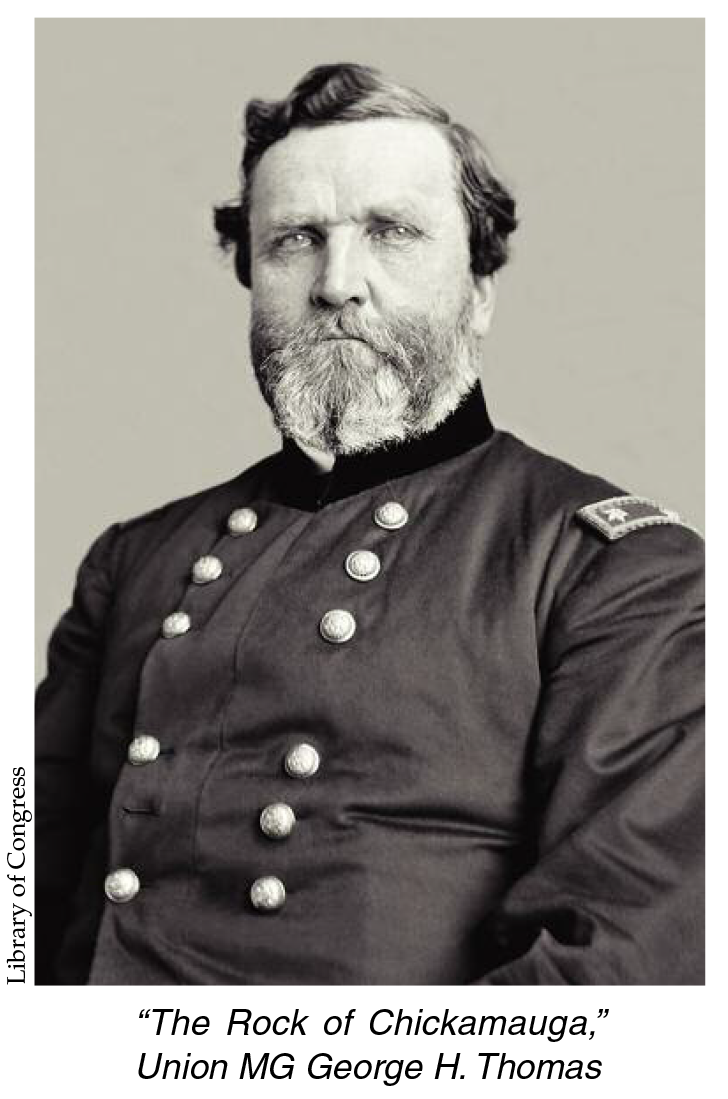

He began to speak in a low, even voice. He told us about how, long ago in the Civil War, at the momentous Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia, Union MG George H. Thomas was

placed in charge of the rear guard. As the Union defense began to collapse, Thomas fought stubbornly through the long day, buying time for the rest of the Army to withdraw.

He took a fearful pounding but held his ground, earning immortal fame as "the Rock of Chickamauga." Many of us knew the story. The colonel leaned forward intently. "Here's

the part you don't know," he intoned. As night fell, Thomas decided to disengage and fall back on Chattanooga, but someone would have to cover his retreat. Later, I

looked it up. The bitter task fell to three Yankee regiments: the 22nd Michigan and the 21st and 89th Ohio. By a strange twist of fate, all three were "orphans." The 22nd had only

recently arrived from Nashville and was new to the Army. The 21st belonged to the division of MG James S. Negley, who had loaned it to another general before fleeing the field.

The 89th, which belonged to an entirely different corps, had been placed under BG James B. Steedman's 1st Division of the Union Reserve Corps. In modern parlance, all

were attachments and not organic to Thomas' corps.

We could see where this was going. The old man continued his tale.Library of Congress In pitch darkness, the three orphan regiments were ordered to hold the ridge "at all hazards."

The Yankees could have thrown down their weapons and fled, but instead they held their ground. The survivors were captured and marched off to prison camp, where they were to languish

for months on end. But Thomas got away, to great glory. The colonel paused in his story. We waited expectantly. "A few days after we land, we're going to come under command of another

division headquarters, flying in to take charge. They're not like us. They're from another tribe, and this time, we'll be the attachments. So just remember: The Chickamauga Rule is in effect."

We went to bed, considerably sobered. The next day, we boarded the planes and flew away to begin our mission. The weather was harsh, the conditions were brutal, and the area of

operations was littered with land mines. We could handle all that, but much to our chagrin, the colonel had been right about the Chickamauga Rule. In our first week, the S-4 was hauled before the divisiondivision headquarters, flying in to take charge. They're not like us. They're from another tribe, and this time, we'll be the attachments. So just remember: The Chickamauga Rule is in effect."

We went to bed, considerably sobered. The next day, we boarded the planes and flew away to begin our mission. The weather was harsh, the conditions were brutal, and the area of

chief of staff for commandeering leftover U.N. rations. (Our resupply aircraft had been diverted to fly in more of the division staff, and our troops were out of chow.) Our new

bosses had occupied all the choice real estate, so we set up our headquarters in a bombed-out warehouse, shivering at 14 degrees below freezing. Our soldiers, manning the

perimeter of an old Soviet air base, lived in miserable conditions with no hot showers or hot food. Day by day, our missions expanded: run the division mess hall, run the ammunition

supply point, run the airfield departure and arrival control group, run checkpoints on the zone of separation, and man the Russian sector, as the Russians had been delayed. Despite our

best efforts, we seemed unable to please our irascible division commander. We prided ourselves on our toughness and our ability to improvise and get the job done, but we were at the breaking point, and

tempers began to flare. The colonel did his best to manage relations with our higher headquarters, and his best was pretty good. He was ably assisted by our sergeant major, a wise and fearless

man who could charm or punch as the situation required. Nevertheless, we continued to get the short end of the stick. Then, as so often happens in the Army, help showed up

when least expected. We often saw the division command sergeant major trudging about on foot in the snow, rifle in hand, at all hours of the day and night, checking up on soldiers. He seemed to have no

love for headquarters, nor did he buy in to the long-standing rivalry between the Germany-based tankers and the south-of-the-Alps airborne. He just liked soldiers, whatever their size and

shape. One night, while checking our positions, I ran into him. Over a canteen cup of coffee, I explained that the headquarters commandant had banned our troopers from the only buildings

with hot showers. Could he help? He winked at me. "Tell you what. Every night, the commanding general has a commander's update. It lasts about two hours. There are four showers

next to his hooch. If you gu ys are as good as I think you are, you ought to be able to run a platoon in there every night while he's out. Try not to get caught, but if you do, I'll cover for

you." We did, and morale soared. When this great soldier became the Sergeant Major of the Army, none of us was surprised. A few days later, an angry company commander came to

see me. He had been task ed to transport two allied officers by ground to their headquarters. "It's a 12-hour movement," he expostulated, "in the dead of winter, through the

snow, there's six million mines in this country, and we have no mine maps of the area. Why can't we wait a day or two for the weather to clear and fly them? This doesn't pass the

common sense test. He was dead right. The colonel and the S-3 were out patrolling the Russian sector, and as the second in command, this was now my problem.

I took the angry captain to see the division operations officer, who replied blandly," You airborne guys are always complaining. Follow your orders." We next tried the chief

of staff, who also roughed us up. Continuing up the chain, I approached the one-star assistant division commander. He was a small man, wizened and merry, with a mangled

hand and a missing foot on account of his service in Vietnam. "What can I do for you?" he beamed. I blurted out our problem. He paused thoughtfully. After a moment, he

said, "You're absolutely right." Holding up what was left of his right hand, he said, "I've already got that T-shirt. I'll take care of it." He did, and morale soared.

For weeks we soldiered on, and few days were fun or easy. That's life on real-world operations. We never really overcame our status as orphans, but when things got really

tough, we had friends in high places. In later years, our colonel would rise to the top of the Army, and many of us would go on to command battalions and brigades of our

own. Along the way, we learned many lessons. One we never forgot was to take special care of our orphans. The Chickamauga Rule taught us that.

This article was broguht to you courtisy of the Association of the United States Army. Visit their website for full publications here: http://www.ausa.org/publications/Pages/default.aspx

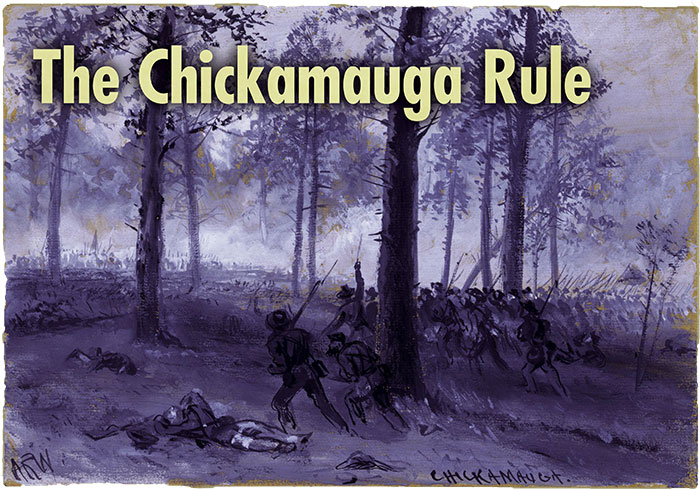

Illustration:

Civil War illustrator Alfred R. Waud sketched

Confederate troops advancing through the

forest toward Union troops at the Battle of

Chickamauga, Ga.