1814-1840 Chapter VII LIFE IN THE FOURTH DECADE

CHAPTER VII.

LIFE AND MANNERS IN THE FOURTH DECADE

By the census of 1830 the United States had a population of 12,866,020, the increase having been for the preceding ten years about sufficient to double the inhabitants in thirty years. There were twenty-four States, Indiana having been taken into the Union in 1816, Mississippi in 1817, Illinois in 1818, Alabama in 1819, Maine in 1820, and Missouri, the last, in 1821. Florida, Michigan, and Arkansas were the Territories. The area, now that Florida had been annexed, was 725,406 square miles.

Comparatively little of the soil of Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin had as yet been occupied, though settlements were making on most of the larger streams. The southwest had at this time filled up more rapidly than the northwest.

In 1830 the centre of population for the Union was farther south than it has ever been at any other time. Except in Louisiana and Missouri, not over thirty thousand inhabitants were to be found west of the Mississippi. The vast outer ranges of the Louisiana purchase remained a mysterious wilderness. Indianapolis in 1827 contained twenty-five brick houses, sixty frame, and about eighty log houses; also a court-house, a jail, and three churches. Chicago was laid out in 1830. Thither in, 1834 went one mail per week, from Niles, Mich., on horseback. In 1833 it was incorporated as a town, having 175 houses and 550 inhabitants. That year it began publishing a newspaper and organized two churches. In 1837 it was a city, with 4,170 inhabitants. The Territory of Iowa had in 1836, 10,500 inhabitants; in 1840, 43,000. At this time Wisconsin had 31,000. So early as 1835 Ohio had nearly or quite 1,000,000 inhabitants. Sixty-five of its towns had together 125 newspapers.

111

John Tyler

From a photograph by Brady.

Between 1830 and 1840 Ohio's population rose from 900,000 to 1,500,000; Michigan's, from 30,000 to 212,000; and the whole country's, from 13,000,000 to 17,000,000. Before 1840, eight steamers connected Chicago with Buffalo.

By 1840 nearly all the land of the United States this side the Mississippi had been taken up by settlers. The last districts to be occupied were Northern Maine, the Adirondack region of New York, a strip in Western Virginia from the Potomac southward through Kentucky nearly to the Tennessee line, the Pine Barrens of Georgia, and the extremities of Michigan and Wisconsin. Beyond the Father of Waters his shores were mostly occupied, as well as those of his main tributaries, a good way from their mouths. The Missouri Valley had population as far as Kansas City. Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa Territory had many settlements at some distance from the streams. The aggregate population of the country was 17,069,453, the average density twenty-one and a tenth to the square mile.

VOL. III.--8

The mass of westward immigration was as yet native, since the great rush from Europe only began about 1847. This was fortunate, as fixing forever the American stamp upon the institutions of western States. To compensate each new commonwealth for the non-taxation of the United States land it contained, it received one township in each thirty-six as its own for educational purposes, a provision to which is due the magnificent school system of Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, and their younger sisters.

Farther east, too, there had, of course, been growth, but it was slower. In 1827 Hartford had but 6,900 inhabitants; New Haven, 7,100; Newark, N. J., ,500, and New Brunswick about the same. The State of New York paid out, between 1815 and 1825, nearly $90,000 for the destruction of wolves, showing that its rural population had attained little density. The entire country had vastly improved in all the elements of civilization. A national literature had sprung up, crowding out the reprints of foreign works which had previously ruled the market.

Bryant, Cooper, Dana, Drake, Halleck, and Irving were now re-enforced by writers like Bancroft, Emerson, Hawthorne, Holmes, Longfellow, Poe, Prescott, and Whittier. Educational institutions were multiplied and their methods bettered, The number of newspapers had become enormous. Several religious journals were established previous to 1830, among them the New York Observer, which dates from 1820, and the Christian Register, from 1821. Steam printing had been introduced in 1823. The year 1825 saw the first Sunday paper; it was the New York Sunday Courier. Greeley began his New York Tribune only in 1841.

Fresh news had begun to be prized, as shown by the competition between the two great New York sheets, the Journal of Commerce and the Morning Enquirer, each of which, in 1827, established for this purpose swift schooner lines and pony expresses. The Journal oj Commerce in 1833 put on a horse express between Philadelphia and New York, with relays of horses, enabling it to publish congressional news a day earlier than any of its New York contemporaries.

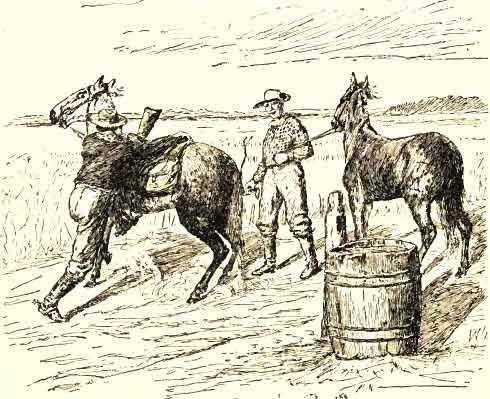

A Pony Express.

Other papers soon imitated this example, whereupon the Journal extended its relays to Washington. Mails came to be more numerous and prompt. More letters were written, and, from 1839, letters were sent in envelopes. Postage-stamps were not used till 1847.

Most of the principal cities in the country, including Rochester and Cincinnati, published dailies before 1830. Baltimore and Louisville had each a public school in 1829. This year witnessed in Boston the beginning work of the first blind asylum in the country. In Hartford instruction had already been given to the deaf and dumb since 1817.

By the fourth decade of the century the American character had assumed a good deal of definiteness and greatly interested foreign travellers. There was, by those who knew what foreign manners were, much foolish aping of the same. English visitors noted Brother Jonathan's drawl in talking, his phlegmatic temperament, keen eye, and blistering inquisitiveness. Jonathan was a rover and a trader, everywhere at home, everywhere bent upon the main chance. He ate too rapidly, chewed and smoked tobacco, and spat indecently. He drank too much. During the first quarter of the century nearly everyone used liquor, and drunkenness was shamefully common.

Every public entertainment, even if religious, set out provision of free punch. At hotels, brandy was placed upon the table, free as water to all. The smaller sects often held preaching services in bar-rooms for lack of better accommodations. On such occasions the preacher was not infrequently observed, without affront to anyone, to refresh himself from behind the bar just before announcing his text.

In 1824 commenced in Boston a temperance movement which accomplished in this matter the most happy reform. It swept New England, passing thence to all the other parts of the Union. By the end of 1829 over a thousand temperance societies were in existence. The distilling and importation of spirits fell off immensely. It became fashionable not to drink, and little by little drinking came to be stigmatized as immoral.

By the time of which we now speak, the old habit of expressing solicitude for the fate of the Union had passed away. Whig like Democrat--so different from old Federalist-swore by "the people."

Every American believed in America. Travelling abroad, the man from this country was wont to assume, and if opposed to contend, ill-manneredly sometimes, that its institutions were far the best in the world. No one wished a change. The unparalleled prosperity of all contributed to this satisfaction. Cities and towns came up in a day. Public improvements were to be seen making in every direction. There was no idle aristocracy on the one hand, no beggars on the other. Self-respect was universal. The people held the power. If men attained great wealth, as not a few did, they usually did not waste it but invested it. Business enterprise was intense and common. Character entered into credit as an element along with financial resources. People did not crowd into cities, but loved and built up the country rather. Laws and penalties were become more mild. In 1837 a man was flogged at the whipping-post in Providence, R. I., for horse-stealing, perhaps the last case of the kind in the country.

Prisons were now made clean and healthy, and the idea of reforming the criminal instead of taking vengeance upon him was spreading. Reformatories for children had been opened in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. There were institutions for homeless children, for the sick poor, for the insane, and for other unfortunate classes.

By this time the Methodists and Baptists had become extremely strong in numbers. In 1833 the Massachusetts constitution was altered, abolishing obligatory contributions for the support of the ministry of the standing order. Connecticut had made the same change fifteen years before, in its constitution of 1818. In many localities the newer denominations, hitherto sects, were more influential than the old one, and in this abolition of ecclesiastical taxes they had with them Jews, atheists, deists, agnostics, and heathen.

About 1825 began a period of peculiar religious enthusiasm. Missions to the heathen were instituted. Revivals were numerous and often shook whole neighborhoods for weeks and months. About this date Millerism began to make converts. William Miller, from whom it took its name, preached far and wide that the world would be destroyed in 1843, securing multitudes of disciples, who clung to his general belief even after his prophecy as to the specific date for the final catastrophe was seen to have failed. Mormonism was also founded, in 1830, and the Book of Mormon published by Joseph Smith. A church of this order, organized this year at Manchester, N. Y., removed the next to Kirtland, O., and thence to Independence, Mo. Driven from here by mob violence, they built the town of Nauvoo, Ill. Meeting in this place too with what they regarded persecution, several of their members being prosecuted for polygamy, they were obliged to migrate to Salt Lake City, where, however, they were not fully settled until 1848.

As part of the same general stir we may perhaps register the anti-masonic movement. One William Morgan, a Mason residing in Western New York, was reported about to expose in a publication the secrets of that order. The Masons were desirous of preventing this and made several forcible efforts to that end. Morgan was soon missing, and the exciting assumption was almost universally made that the Masons had taken him off. There was much evidence of this; but conviction was found impossible because, as was alleged, judges, juries, and witnesses were nearly all Masons. An intense and widespread feeling was developed that Masonry held itself superior to the laws, was therefore a foe to the Government and must be destroyed. The Anti-Masons became a mighty political party. Masons were driven from office. In 1832 anti-masonic nominations were made for President and Vice-President, which had much to do with the small vote of Clay in that year. It was this party that brought to the front politically William H. Seward, Millard Fillmore, and Thurlow Weed.

Thurlow Weed.

From an unpublished Photograph by Disderi, Paris, in 1861.

In the possession of Thurlow Weed Barnes.

In 1833 Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania passed laws suppressing lotteries, but the gambling mania seemed to transform itself into a craze for banks. In many parts this was such that actual riots took place when subscriptions to the stock of banks were opened, the earliest comers subscribing the whole with the purpose of selling to others at an advance. To make a bank was thought the great panacea for every ill that could befall. In this we see that the American people, bright as they were, could be duped.

Less wonder, then, at the success of the Moon Hoax, perpetrated in 1835. It was generally known that Sir John Herschel had gone to the Cape of Good Hope to erect an observatory. One day the New York Sun came out with what purported to be part of a supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science, giving an account of Herschel's remarkable discoveries. The moon, so the bogus relation ran, had been found to be inhabited by human beings with wings. Herschel had seen flocks of them flying about. Their houses were triangular in form.

The telescope had also revealed beavers in the moon, exhibiting most remarkable intelligence. Pictures of some of these and of moon scenery accompanied the article. The fraud was so clever as to deceive learned and unlearned alike. The sham story was continued through several issues of the Sun, and gave the paper an enormous sale. As it arrived in the different places, crowds scrambled for it, nor would those who failed to secure copies disperse until some one more fortunate had read to them all that the paper said upon the subject. Several colleges sent professorial deputations to the Sun office to see the article, and particularly the appendices, which, it was alleged, had been kept back. Richard Adams Locke was the author of this ingenious deception, which was not exploded until the arrival of authentic intelligence from Edinburgh.

Party spirit sometimes ran terribly high. A New York City election in 1834 was the occasion of a riot between men of the two parties, disturbances continuing several days. Political meetings were broken up, and the militia had to be called out to enforce order. Citizens armed themselves, fearing attacks upon banks and business houses. When it was found that the Whigs were triumphant in the city, deafening salutes were fired. Philadelphia Whigs celebrated this victory with a grand barbecue, attended, it was estimated, by fifty thousand people. The death of Harrison was malignantly ascribed to overeating in Washington, after his long experience with insufficient diet in the West. Whigs exulted over Jackson's cabinet difficulties. Jackson's "Kitchen Cabinet," the power behind the throne, gave umbrage to his official advisers. Duff Green, editor of the United States Telegraph, the President's "organ," was one member; Isaac Hill, of New Hampshire, and Amos Kendall, first of Massachusetts, then of Kentucky, were others, these three the most influential. All had long worked, written, and cheered for Old Hickory.

In return he gave them good places at Washington, and now they enjoyed dropping in at the White House to take a smoke with the grizzly hero and help him curse the opposition as foes of "the people."

Major Eaton, Old Hickory's first Secretary of War, had married a beautiful widow, maiden name Peggy O'Neil, of common birth, and much gossipped about. The female members of other cabinet families refused to associate with her, the Vice-President's wife leading. Jackson took up Mrs. Eaton's cause with all knightly zeal. He berated her traducers and persecutors in long and fierce personal letters. His niece and housekeeper, Mrs. Donelson, one of the anti-Eatonites, he turned out of the White House, with her husband, his private secretary. The breach was serious anyway, and might have been far more so but for the healing offices of Van Buren, who used all his courtliness and power of place to help the President bring about the social recognition of Mrs. Eaton.

LIFE AND MANNERS

He called upon her, made parties in her honor, and secured her entree to the families of the greatest foreign ministers. Mrs. Eaton triumphed, but the scandal would not down.

When Jackson wrote his foreign message upon the French spoliation claims, his cabinet were aghast and begged him to soften its tone. Upon his refusal, it is said, they stole to the printing-office and did it themselves. But the proofs came back for Jackson's perusal. The lad who brought them was the late Mr. J. S. Ham, of Providence, R. I. He used to say that he had never known what profane swearing was till he listened to General Jackson's comments as those proofs were read.

Jackson and Quincy Adams were personal as well as political foes. When the President visited Boston, Harvard College bestowed on him the degree of Doctor of Laws. Adams, one of the overseers, opposed this with all his might. As "an affectionate child of our Alma Mater, he would not be present to witness her disgrace in conferring her highest literary honors upon a barbarian."

VOL. III.--9

Subsequently he would refer, with a sneer, to "Dr. Andrew Jackson." The President's illness at Boston Adams declared "four-fifths trickery" and the rest mere fatigue. He was like John Randolph, said Adams, who for forty years was always dying. "He is now alternately giving out his chronic diarrhoea and making Warren bleed him for a pleurisy, and posting to Cambridge for a doctorate of laws, mounting the monument of Bunker's Hill to hear a fulsome address and receive two cannon-balls from Edward Everett."

To be sure, manifestations of a contrary spirit between the political parties were not wanting. The entire nation mourned for Madison after his death in 1836, as it had on the decease of Jefferson and John Adams both on the same day, July 4, 1826.

A note or two upon costume may not uninterestingly close this chapter.

Enormous bonnets were fashionable about 1830. Ladies also wore Leghorn hats, with very broad brims rolled up behind, tricked out profusely with ribbons and artificial flowers. Dress-waists were short and high. Skirts were short, too, hardly reaching the ankles. Sleeves were of the leg-of-mutton fashion, very full above the elbows but tightening toward the wrist. Gentlemen still dressed for the street not so differently from the revolutionary style. Walking-coats were of broadcloth, blue, brown, or green, to suit the taste, with gilt buttons. Bottle-green was a very stylish color for evening coats. Blue and the gilt buttons for street wear were, however, beginning to be discarded, Daniel Webster being one of the last to walk abroad in them. The buff waistcoat, white cambric cravat, and ruffled shirt still held their own. Collars for full dress were worn high, covering half the cheek, a fashion which persisted in parts of the country till 1850 or later.