1860-1868 Chapter IV WAR BEGUN

CHAPTER IV.

WAR BEGUN

It was now apparent to both North and South that war was inevitable. Yet neither side believed the other in full earnest or dreamed of a long struggle. Sanguine northerners looked to see the rebellion stamped out in thirty days. The more cautious allowed three months.

The President, however, soon saw that more troops, enlisted for a longer term, would be necessary. At the outset the South certainly possessed decided advantages: greater earnestness, more men of leisure aching for war and accustomed to saddle and firearms, a militia better organized, owing to fear of slave insurrections, and now for a long time in special training, and withal a certain soldierly fire and dash native to the people. The South also had superior arms.

Enlistments there were prompt and abundant. The troops were ably commanded, 262 of the 951 regular army officers whom secession found in service, including many very high in rank, joining their States in the new cause, besides a large number of West Point graduates from civil life.

Accordingly on May 3d Mr. Lincoln issued a new call for troops, 42,000 volunteers to serve three years or during the war, 23,000 regulars, and 18,000 seamen. It was of first importance to secure Maryland for the Union. On the night of May 13th, under cover of a thunderstorm, General Butler suddenly entered rebellious Baltimore with less than 1,000 men, and entrenched upon Federal Hill. Overawed by this bold move, the secessionists made no resistance. A political reaction soon set in throughout the State, which became firmly Unionist. Baltimore was once more open to the passage of troops, who kept steadily hurrying to the front.

Meanwhile the Confederate forces were getting uncomfortably close to Washington. From the White House a secession flag could be seen flying at Alexandria, which was occupied by a small pro-secession garrison.

Captain Nathaniel Lyon.

There was fear lest that party would occupy Arlington Heights, across from Washington, and thence pour shot and shell into the city. At two o'clock on the morning of May 24th, eight regiments crossed the Potomac and took possession of these hills as far south as Alexandria, and fortified them.

The latter place was entered by Colonel Ellsworth with his famous New York Zouaves. No resistance was made, as the Confederates had retired, but Ellsworth was brutally assassinated while hauling down the secession flag.

Upon the secession of Virginia the Confederate capital was removed to Richmond. The main armies of both sides were now encamped on Old Dominion soil, and at no great distance apart; but the commanders were busy drilling their raw troops, so that for a time only trifling engagements occurred. General Butler, with a considerable body of men, was occupying Fortress Monroe, at the mouth of the James River. June 10th, an expedition sent by him against the Confederates at Big Bethel, some twelve miles distant, was repulsed after a spirited attack, with a total loss of sixty-eight. A week later an Ohio regiment took the cars to make a reconnoissance toward Vienna, a village not far south of Washington.

They were surprised by Confederates, who placed two guns on the track and fired on the train as it came around a curve. The Ohioans sprang to the ground, and after some fighting drove their opponents back.

All this time both North and South were struggling for possession of the neutral States. Governor Jackson, of Missouri, was straining every nerve to force his State into secession. Early in May two or three regiments of militia were got together and drilled in a camp near St. Louis. Cannon were sent by President Davis, boxed up and marked "marble." Captain Lyon, of the regular army, who held the St. Louis arsenal with a few companies, reconnoitred the secessionist camp in female dress. The next day, May 10th, assisted by local militia, he suddenly surrounded it and took 1,200 prisoners. A month later he embarked some soldiers on three swift steamers, sailed up the Missouri to Jefferson City, the state capital, and raised the Union flag once more over the State House. Governor Jackson fled. During the next month all the armed disunionists were driven into the southwestern part of the State.

General John C. Fremont.

The last of July a state convention organized a provisional government and declared for the Union. But the secessionists, under General Price, continued the struggle. The Union forces, after a brave fight against great odds at Wilson's Creek, August 10th, in which Lyon was killed, had to retreat north. General Fremont had shortly before been put at the head of the Western Department, which included Missouri, Kentucky, Illinois, and Kansas. His difficulties were great. He was unable to clear the State of secessionists, who besieged Lexington and took it on September 20th. Generals Hunter and Halleck, Fremont's successors, were equally unsuccessful, and the State was harassed by a petty warfare all the year.

In Kentucky, Governor Magoffin was inclined to secession. The Legislature leaned the other way, but preferred neutrality to active participation on either side. September 6th, Brigadier-General U. S. Grant occupied Paducah, an important strategical point at the junction of the Ohio and Tennessee rivers. Next day the Confederate General Polk, advancing from below, took possession of Columbus on the Mississippi. With both hostile armies thus encamped on her soil, Kentucky could no longer be neutral.

Her decision was quickly taken. The Legislature demanded of President Davis to withdraw Polk's forces, at the same time calling upon General Anderson, the hero of Sumter, who had been placed in charge of the Department of the Cumberland, to take active measures for the defence of this his native State.

The mountain portion of Virginia belonged to the West rather than to the South. It contained only 18,000 slaves, against nearly 500,000 in Eastern Virginia. Union sentiment was therefore strong, and when the old State seceded from the Union, Western Virginia proceeded to secede from the State. General Lee sent troops to hold it for the Confederacy. Thereupon General McClellan, commanding the Department of the Ohio, threw several regiments across the river into Virginia, and defeated the foe in minor engagements at Philippi, Rich Mountain, and Carrick's Ford. By the middle of July he was able to report, "Secession is killed in this country." Later in the year the Confederates renewed their attempts, but were finally driven out. West Virginia organized a separate government, and was subsequently admitted to the Union as a State by itself.

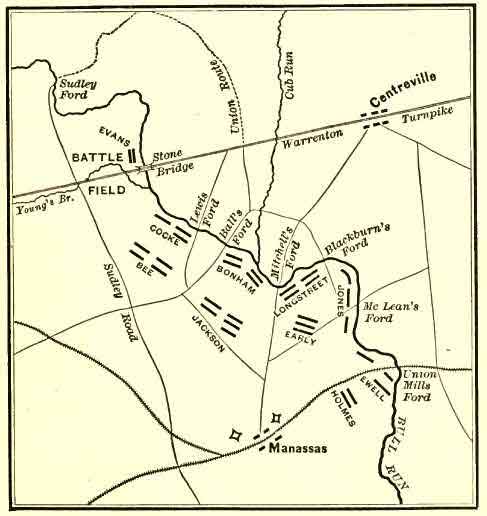

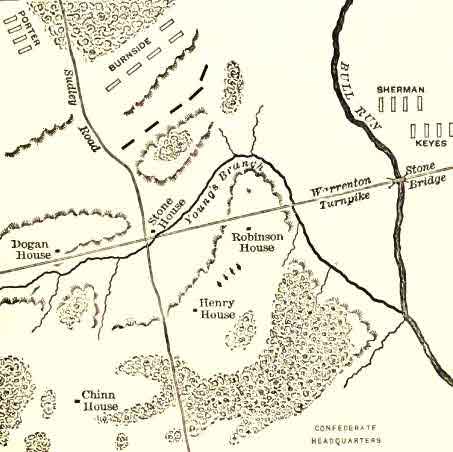

Bull Run--the Field of Strategy.

While these struggles were going on in the border commonwealths, the Union soldiers lay inactive along the Potomac. Constant drill had changed the mob into some semblance of an organized army, but the careful Scott feared to risk a general engagement. The hostile forces stretched in three pairs of groups across Virginia from northwest to southeast. In the southeastern part of the State, at Fortress Monroe, Butler faced the Confederate Magruder. At Manassas, opposite Washington, and about thirty miles southwest, lay a Confederate army under General Beauregard. General Patterson, a veteran of the War of 1812, commanded considerable forces in Southern Pennsylvania. About the middle of June he advanced against Harper's Ferry, which had been abandoned by the Unionists the latter part of April and was now occupied by General Joseph E. Johnston. Johnston evacuated the place upon Patterson's approach, and retreated up the Shenandoah Valley, in a southwesterly direction, to Winchester. Patterson followed part way, and the two armies now lay watching each other.

Anxious to see the rebellion put down by one blow, the North was becoming impatient. "On to Richmond!" was the ceaseless cry. Yielding to this, Scott ordered an advance. July 16th, General McDowell, leaving one division to protect Washington, led forth an army 28,000 strong to attack the enemy at Manassas.

General Irvin McDowell.

VOL. III.--23

He advanced slowly and with great caution. The enemy were found posted in a line eight miles long upon the south bank of Bull Run, a small river three miles east of Manassas, running in a southeasterly direction. Several days were spent in reconnoitering. Meanwhile, Johnston, whom Patterson was expected to hold at Winchester, had stolen away to join Beauregard, their combined forces numbering about 30,000. McDowell was ignorant of Johnston's movement, supposing him still at Winchester.

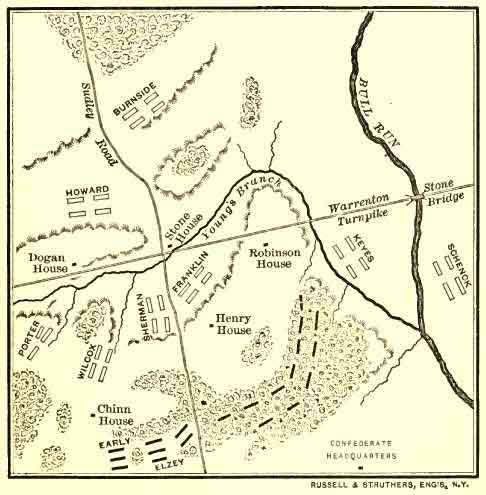

On the morning of the 21st McDowell advanced to the attack. Beauregard held all the lower fords, besides a stone bridge on the Warrenton turnpike which crosses the river at right angles. Two divisions, under Hunter and Heintzelman, were set in motion before sunrise to make a flanking detour and cross Bull Run at Sudley's Ford, some distance farther up. To distract attention from this movement, Tyler's division began an attack at the stone bridge. This was held by a regiment and a half, with four guns, under General Evans.

WAR BEGUN 355

He replied vigorously at first, but perceiving after a while that Tyler was only feigning, and learning of the flank movement above, he left four companies at the bridge and drew up the rest of his forces on a ridge north of Warrenton turnpike to await Hunter and Heintzelman's approach down the Sudley road.

General Samuel P. Heintzelman.

The fight began about ten o'clock. Both sides were soon re-enforced. After two hours' stubborn fighting the Confederates were driven back across the pike, beyond Young's Branch of Bull Run, and took up a second position on a hill each side of the Henry House. The whole Union force had now crossed Bull Run.

Griffin's and Ricketts' powerful batteries were posted in favorable positions, whence they poured a deadly fire upon the Confederates. The whole Union line advanced to the turnpike. About two o'clock the Confederates were forced to abandon their second position and fall back still farther.

Early in the morning Beauregard and Johnston had given orders for an attack upon the Union forces across the river, not knowing that McDowell had assumed the offensive. These orders were now countermanded, and all available troops hurried up the Sudley road toward the Warrenton pike front. Till after noon the prospect for the Confederates looked gloomy. They had been steadily driven back. Some of their regiments had lost heavily, while all were more or less demoralized. Johnston and Beauregard gave their personal direction to re-forming the line upon a second ridge to the south of the Warrenton pike, under cover of a semicircular piece of woods. Twelve regiments, with twenty-two guns and two companies of cavalry, concentrated in this favorable position and awaited the Union advance.

Bull Run-Battle of the Forenoon.

McDowell had fourteen regiments available for the attack. He decided to hurl them against the Confederate centre and left. About half-past two Griffin's and Ricketts' batteries took up an advanced position on Henry Hill.

The Confederate guns opened fire, and a short artillery duel took place. A Confederate regiment now advances to capture the exposed batteries. They are mistaken for Union re-enforcements and allowed to come within close range. The muskets are levelled. A terrible volley is poured into the batteries. The gunners are stricken down. The frantic horses dash madly down the hill. After a little confusion the Union troops boldly advance and retake the batteries. The battle surges back and forth. The guns are three times captured and lost again. The fight becomes general along the Confederate centre and left. The Union generals are getting alarmed. So far they have been confident of victory. Now regiment after regiment is going to pieces in this terrific melee, and still the "rebels" hold their ground. About half-past four o'clock General Early arrives by rail with three thousand more of Johnston's army, and, assisted by a battery and five companies of cavalry, bursts upon the extreme right flank and rear of McDowell's line.

Bull Run--Battle of the Afternoon.

This manoeuvre decided the day. The Union ranks waver, break, flee. The centre and left soon follow, though in better order. Union and Confederate generals alike were astonished at the sudden change. McDowell found it impossible to stem the tide once set in, and gave orders to fall back across Bull Run to Centreville, where his reserves were stationed.

As the retreat went on it turned to a downright rout. The Confederates made only a feeble pursuit, but fear of pursuit spread alarm through the flying ranks, demoralized by long marching and hard fighting. Baggage and ammunition-wagons, ambulances, private vehicles which had been standing in the rear, joined the sweeping tide, adding to the confusion and in some places causing temporary blockade. Frightened teamsters cut traces and galloped recklessly away. Panic and stampede resulted, soon reaching the soldiers. Flinging away muskets and knapsacks, they sought safety in flight. The army entered Centreville a disorganized mass. Fugitives could not be stayed even there, but streamed through and on toward Washington. McDowell gave the order to continue the retreat. The reserve brigades, with the one regiment of regulars, covered the rear in good order. All that night the crazy hustle to the rear was kept up, and on Monday the hungry and exhausted stragglers poured into Washington under a drizzling rain, the people receiving them with heavy hearts but generous hands.

General Joseph E. Johnston.

The Union loss was 481 killed, 1,011 wounded, 1,460 prisoners. Twenty-five guns were lost, thirteen of them on the retreat. The Confederate loss was 387 killed, 1,580 wounded.

The numbers actively engaged were about 18,000 on each side. General Sherman pronounced Bull Run "one of the best planned battles of the war, but one of the worst fought." The latter fact was but natural. The troops on both sides were poorly drilled, and most of them had never been under fire before. Precision of movement, concert of action on any large scale, were impossible. Neither side needed to be ashamed of this initial trial.

The North was at first much cast down. The faint-hearted considered the Union hopelessly lost, but pluck and patriotism carried the day. On the morrow after the battle Congress voted that an army of 500,000 should be raised, and appropriated $500,000,000 to carry on the war. General McClellan, whose brilliant campaign in West Virginia had won him easy fame, was put in command of the Army of the Potomac. The young general was a West Point graduate and had served with distinction in the Mexican War. An accomplished military student, a skilful engineer, and a superb organizer, he threw himself with energy into the task of fortifying Washington and building up a splendid army.

WAR BEGUN 363

General George B. McClellan.

Many of the three-months volunteers re-enlisted. Thousands of new recruits came flocking to camp, and before long companies, regiments, and brigades amounting to 150,000 men were drilling daily on the banks of the Potomac, while formidable works crowned the entire crest of Arlington Heights. In October the aged General Scott resigned, and McClellan, at the summit of his popularity with army and people, became commander-in-chief.

For several weeks after Bull Run it was feared that Beauregard and his men would descend upon Washington, then in a defenceless condition; but they were in no state to attack. They too felt the need of preparation for the coming struggle, whose magnitude both sides now began to realize.

A disheartening affair occurred in October. On the night of the 20th two Massachusetts regiments crossed the Potomac at Ball's Bluff, a few miles above Washington, to surprise a hostile camp which according to rumor had been established there. A large force concealed in the woods attacked and forced them to retreat. They were re-enforced by 1,900 men under Colonel Baker. The enemy were also re-enforced. Baker was killed and the Union soldiers driven over the bluff into the river. The boats were totally inadequate in number, and the men had to make their way across as best they could, exposed to the Confederate fire. The total Union loss was 1,000.

WAR BEGUN

On the whole, then, the South had reason to be gratified with the aggregate result of the first year of war. Bull Run gave the Confederates a sense of invincibility, and the ready recognition by the foreign powers of their rights as belligerents, offered hope that England would soon acknowledge their independence itself. And they thought that the North had been doing its best when it had only been getting ready.

END OF VOLUME III.