1868-1888 Chapter I POLITICAL HISTORY (2)

PERIOD V.

THE CEMENTED UNION

CHAPTER I.

POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE LAST TWO DECADES

The presidential election of 1868 was decided at Appomattox. General Grant was borne to the White House on a floodtide of popularity, carrying twenty-six out of the thirty-four voting States. Schuyler Colfax, of Indiana, became Vice-President. The Democrats had nominated Horatio Seymour, of New York, and F. P. Blair, of Missouri. Reconstruction was the great issue. The democratic platform demanded universal amnesty and the immediate restoration of all the commonwealths lately in secession, and insisted that the regulation of the franchise should be left with States.

The management of the South was the most serious problem before the new administration. The whites were striving by fair means and foul to get political power back into their own hands. The reconstructed state governments, dependent upon black majorities, were too weak for successful resistance. The Ku-Klux and similar organizations were practically a masked army. The President was appealed to for military aid, and he responded. Small detachments of United States troops hurried hither and thither. Wherever they appeared resistance ceased; but when fresh outbreaks elsewhere called the soldiers away, the fight against the hated state government was immediately renewed. The negroes soon learned to stay at home on election day, and the whites, once in the saddle, were too skilful riders to be thrown.

Congress, meanwhile, still strongly republican, was taking active measures to protect the blacks. In 1870 it passed an act imposing fines and damages for a conspiracy to deprive negroes of the suffrage. The Force Act of 1871 was a much harsher measure. It empowered the President to employ the army, navy, and militia to suppress combinations which deprived the negro of the rights guaranteed him by the Fourteenth Amendment. For such combinations to appear in arms was made rebellion against the United States, and the President might suspend habeas corpus in the rebellious district. By President Grant, in the fall of 1871, this was actually done in parts of the Carolinas. State registrations and elections were to be supervised by United States marshals, who could command the help of the United States military or naval forces.

The Force Act outran popular feeling. It came dangerously near the practical suspension of state government in the South, and many at the North, including some Republicans, thought the latter result a greater evil than even the temporary abeyance of negro suffrage. The "Liberal Republicans" bolted.

In 1872 they nominated Horace Greeley for the Presidency, and adopted a platform declaring local self-government a better safeguard for the rights of all citizens than centralized power. The platform also protested against the supremacy of the military over the civil power and the suspension of habeas corpus, and favored universal amnesty to men at the South. Charles Sumner, Stanley Matthews, Carl Schurz, David A. Wells, and many other prominent Republicans engaged in the opposition.

Thinking their opportunity had come, the Democrats indorsed the Liberals' platform and nominees. The Republicans re-nominated Grant by acclamation, and joined with him on the ticket Henry Wilson, of Massachusetts.

As the campaign went on, the Greeley movement developed remarkable strength and remarkable weakness. Speaking for years through the New York Tribune, Mr. Greeley had won, in a remarkable degree, the respect and even the affection of the country.

His offer to give bail for Jefferson Davis in his imprisonment, and his stanch advocacy of mercy to all who had engaged in secession, so soon as they had grounded arms, made him hosts of friends even in the South, He took the stump himself, making the tour of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, and crowds of Republicans came to see and hear their former champion.

But the Democrats could not heartily unite in the support of such a lifelong and bitter opponent of their party. Some supported a third ticket, while many others did not vote at all. Mr. Greeley, too, an ardent protectionist, was not popular with the influential free-trade element among the Liberals themselves. The election resulted in a sweeping victory for the republican ticket. The Democrats carried but six States, and those were all in the South. Within a month after the election, Mr. Greeley died, broken down by overexertion, family bereavement, and disappointed ambition.

Troubles in the South continued during Grant's second term. The turmoil reached its height in Louisiana in 1874. Ever since 1872 the whites in that State had been chafing under republican rule. The election of Governor Kellogg was disputed, and he was accused of having plunged the State into ruinous debt. In August, 1874, a disturbance occurred which ended in the deliberate shooting of six republican officials. President Grant prepared to send military aid to the Kellogg government. Thereupon Penn, the defeated candidate for Lieutenant-governor in 1872, issued an address to the people, claiming to be the lawful executive of Louisiana, and calling upon the state militia to arm and drive "the usurpers from power." Barricades were thrown up in the streets of New Orleans, and on September 14th a severe fight took place between the insurgents and the state forces, in which a dozen were killed on each side. On the next day the state-house was surrendered to the militia, ten thousand of whom had responded to Penn's call. Governor Kellogg took refuge in the custom-house.

Penn was formally inducted into office. United States troops were hurried to the scene. Agreeably to their professions of loyalty toward the Federal Government, the insurgents surrendered the state property to the United States authorities without resistance, but under protest. The Kellogg government was re-instated.

Troops at the polls secured quiet in the November elections. The returning board decided that the Republicans had elected their governor and fifty-four members of the legislature. Fifty-two members were democratic, while the election of five members remained in doubt, and was left to the decision of the legislature. The Democrats vehemently protested against the decision of the returning board, claiming an all-round victory. Fearing trouble at the assembling of the legislature in January, 1875, President Grant placed General Sheridan in command at New Orleans. The legislature met on January 4th. Our reports of what followed are conflicting.

The admitted facts are that the democratic members, lawfully or unlawfully, placed a speaker in the chair. Some disorder ensuing, United States soldiers were called in and, at the request of the democratic speaker, restored quiet. The Republicans meanwhile had left the house. The Democrats then elected members to fill the five seats left vacant by the returning board. Later in the day, United States troops, under orders from Governor Kellogg, to whom the republican legislators had appealed, ejected the five new members. The Republicans re-entered the house, and the Democrats thereupon withdrew. Subsequently a congressional committee made unsuccessful attempts to settle the dispute. The democratic members finally returned, and a sullen acquiescence in the Kellogg government gradually prevailed.

By 1876 every southern State was solidly democratic except Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, and in these republican governments were upheld only by the bayonet.

The presidential election of 1876 was a contest of general tendencies rather than of definite principles. The opposing parties were more nearly matched than they had been since 1860. The Democrats nominated Samuel J. Tilden, of New York, and Thomas A. Hendricks, of Indiana. Rutherford B. Hayes, of Ohio, and William A. Wheeler, of New York, became the republican standard-bearers. The election passed off quietly, troops being stationed at the polls in turbulent quarters. Mr. Tilden carried New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut. With a solid South, he had won the day. But the returning boards of Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina, throwing out the votes of several democratic districts on the ground of fraud or intimidation, decided that those States had gone republican, giving Hayes a majority of one in the electoral college. The Democrats raised the cry of fraud. Suppressed excitement pervaded the country. Threats were even muttered that Hayes would never be inaugurated. President Grant quietly strengthened the military force in and about Washington. The country looked to Congress for a peaceful solution of the problem, and not in vain.

The Constitution provides that "the President of the Senate shall, in presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the [electoral] certificates, and the votes shall then be counted." Certain Republicans held that the power to count the votes lay with the President of the Senate, the House and Senate being mere spectators. The Democrats naturally objected to this construction, since Mr. Ferry, the republican president of the Senate, could then count the votes of the disputed States for Hayes.

The Democrats insisted that Congress should continue the practice followed since 1865, which was that no vote objected to should be counted except by the concurrence of both houses. The House was strongly democratic; by throwing out the vote of one State it could elect Tilden.

Samuel J. Tilden.

After a pastel by Sarony in the house at Gramercy Park.

The deadlock could be broken only by a compromise. A joint committee reported the famous Electoral Commission Bill, which passed House and Senate by large majorities; 186 Democrats voting for the bill and 18 against it, while the republican vote stood 52 for and 75 against. The bill created a commission of five senators, five representatives, and five justices of the United States Supreme Court, the fifth justice being chosen by the four appointed in the bill. Previous to this choice the commission contained seven Democrats and seven Republicans. It was expected that the fifth justice would be Hon. David Davis, of Illinois, a neutral with democratic leanings; but his unexpected election as democratic senator from his State caused Justice Bradley to be selected to the post of decisive umpire. The votes of all disputed States were to be submitted to the commission for decision.

It was drawing perilously near to inauguration day. The commission met on the last day of January. The cases of Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina were in succession submitted to it by Congress. Eminent counsel appeared for each side. There were double sets of returns from everyone of the States named. In the three southern States the governor recognized by the United States had signed the republican certificates. The democratic certificates from Florida were signed by the state attorney-general and the new democratic governor; those from Louisiana by the democratic gubernatorial candidate, who claimed to be the lawful governor; those from South Carolina by no state official, the Tilden electors simply claiming to have been chosen by the popular vote and rejected by the returning board. In Oregon the democratic governor declared one of the Hayes electors ineligible because an office-holder, and gave a certificate to Cronin, the highest Tilden elector, instead. The other two Hayes electors refused to recognize Cronin, and, associating with them the rejected republican elector, presented a certificate signed by the secretary of state. Cronin, appointing two new electors to act with him, cast his vote for Tilden, his associates voting for Hayes. This certificate was signed by the governor and attested by the secretary of state.

After deciding not to go behind any returns which were prima facie lawful, the commission, by a strict party vote of eight to seven, gave a decision for the Hayes electors in every case. March 2d it adjourned, and three days later Hayes was inaugurated without disturbance.

The whole country heaved a sigh of relief. All agreed that provision must be made against such peril in the future; but it was not till late in 1886 that Congress could agree upon the necessary measure. The Electoral Count Bill was then passed, and signed by the President on February 3, 1887. It aims to throw upon each State, so far as possible, the responsibility of determining how its own presidential vote has been cast. It provides that the President of the Senate shall open the electoral certificates in the presence of both houses, and hand them to the tellers, two from each house, who are to read them aloud and record the votes.

If there has been no dispute as to the list of electors from a State, such list, where certified in due form, is to be accepted as a matter of course. In case of dispute, the procedure is as follows: If but one set of returns appears and this is authenticated by a state electoral tribunal constituted to settle the dispute, such returns shall be conclusive. If there are two or more sets of returns, the set approved by the state tribunal shall be accepted. If there are two rival tribunals, the vote of the State shall be thrown out, unless both houses, acting separately, agree upon the lawfulness of one tribunal or the other. If there has been no decision by a tribunal, those votes shall be counted which both houses, acting separately, decide to be lawful. If the houses disagree, the votes certified to by the governor shall be accepted.

President Hayes's first important action was the withdrawal of troops from South Carolina and Louisiana, where the rival governments existed side by side. The republican governments at once fell to the ground. As the Democrats had already got control in Florida, the "solid South" was now an accomplished fact. Financial questions were those which chiefly occupied the public mind during Hayes's administration. They are referred to in Chapter VII., below.

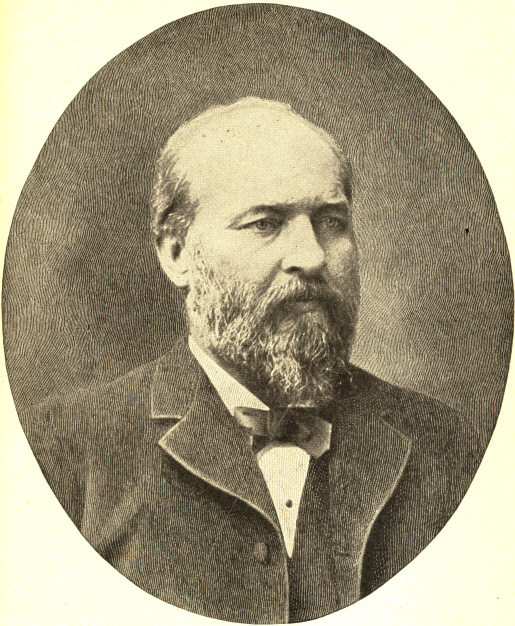

Returning from a remarkable tour around the world, General Grant became in 1880 a candidate for a third-term nomination. The deadlock in the republican convention between him and Mr. Blaine was broken by the nomination of James A. Garfield, of Ohio. Chester A. Arthur, of New York, was the vice-presidential candidate. The Democrats nominated the hero of Gettysburg, the brave and renowned General W. S. Hancock, of Pennsylvania, and William H. English, of Indiana. Garfield was elected, receiving 214 electoral votes against 155 for Hancock. Hancock carried every southern State; Garfield every northern State except New Jersey, Nevada, and California.

President Garfield had hardly entered upon his high duties when he was cut down by the hand of an assassin. On the morning of July 2, 1881, the President entered the railway station at Washington, intending to take an eastern trip. Charles J. Guiteau, a disappointed office-seeker, crept up behind him and fired two bullets at him, one of which lodged in his back. The President died on September 19th, after weeks of suffering. Vice-President Arthur succeeded to the presidency, and had an uneventful but respectable administration.

Guiteau's trial began in November and lasted more than two months. The defence was insanity. The assassin maintained that he was inspired to commit the deed, and that it was a political necessity. The "stalwart" Republicans, headed by Senator Conkling, had quarrelled with the President over certain appointments unacceptable to the New York senator; Guiteau pretended to think the removal of Mr. Garfield necessary to the unity of the party and the salvation of the country.

.

.

From a photograph by C. M. Bell, Washington, D. C.

The prosecution showed that Guiteau had long been an unprincipled adventurer, greedy for notoriety; that he first conceived of killing the President after his hopes of office were finally destroyed; and that he had planned the murder several weeks in advance. Guiteau was found guilty, and executed at Washington on June 30, 1882. The autopsy showed no disease of the brain.

Although it had no logical connection with the "spoils" system, the assassination of President Garfield called the attention of the whole country to the crying need of reform in the civil service. Ever since the days of President Jackson, in 1829, appointments to the minor federal offices had been used for the payment of party debts and to keep up partisan interest. This practice incurred the deep condemnation of Webster, Clay, Calhoun, and others, but no practical steps toward reform were taken till 1871.

222 THE CEMENTED UNION

The abuses of the spoils system had then become so flagrant that Congress created a civil service commission, which instituted competitive examinations to test the merits of candidates for office in the departments at Washington. President Grant reported that the new methods "had given persons of superior capacity to the service'" But Congress, always niggardly in its appropriations for the work of the commission, after 1875 cut them off altogether, and the rules were suspended.

Under President Hayes civil service reform made considerable progress in an irregular way. Secretary Schurz enforced competitive examinations in the Interior department. They were also applied by Mr. James to the New York Post-office, and, as the result, one-third more work was done with less cost. Similar good results followed the enforcement of the "merit system" in the New York custom-house after 1879. President Hayes also strongly condemned political assessments upon office-holders, but with small practical effect.

The alarming increase of corruption in political circles generally, after the war, helped to create popular sentiment for reform. Corrupt "rings" sprang up in every city. The "whiskey ring," composed of distillers and government employees, assumed national proportions in 1874, cheating the Government out of a large part of its revenue from spirits. Liberal appropriations for building a navy were squandered.

During the campaign of 1872, the Democrats charged several prominent Congressmen with having taken bribes, in 1867-68, to vote for legislation desired by the Union Pacific Railroad. At the request of the accused, an examination was had by a House committee. The committee's report in 1873 recommended the expulsion of Representatives Oakes Ames and James Brooks. Mr. Ames was accused of selling to Congressmen at reduced rates, with intent to influence their votes, shares of stock in the "Credit Mobilier," a corporation for the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Mr. Brooks, who was a government director in the railroad, was charged with receiving such shares. The House did not expel the two members, but severely condemned them. Shadows of varying density fell upon many prominent politicians and darkened their subsequent careers.

The tragic fate of President Garfield, following these and other revelations of political corruption, brought public sentiment on civil service reform to a head. A bill prepared by the Civil Service Reform League, and introduced by Senator Pendleton, of Ohio, passed Congress in January, 1883, and on the 16th received the signature of the President.

It authorized the President, with the consent of the Senate, to appoint three civil service commissioners, who were to institute competitive examinations open to all persons desiring to enter the government employ.

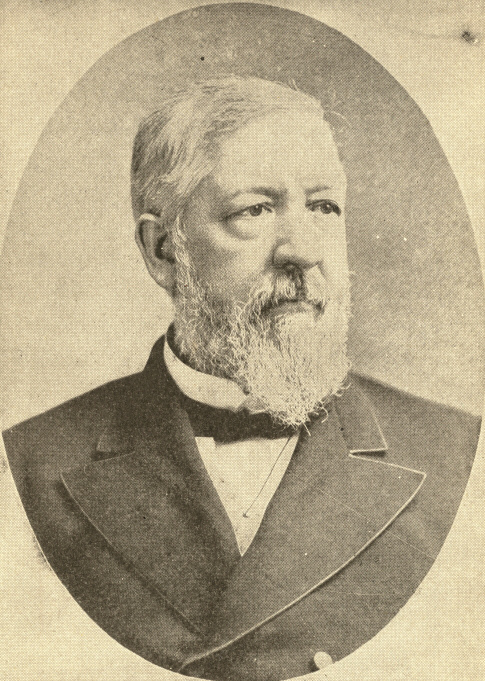

James G. Blaine.

It provided that the clerks in the departments at Washington, and in every customs district or post-office where fifty or more were employed, should be arranged in classes, and that in the future only persons who had passed the examinations should be appointed to service in these offices or promoted from a lower class to a higher, preference being given according to rank in the examinations. Candidates were to serve six months' probation at practical work before receiving a final appointment. The bill struck a heavy blow at political assessments, by declaring that no official should be removed for refusing to contribute to political funds. Congressmen or government officials convicted of soliciting or receiving political assessments from government employees became liable to a five thousand dollar fine, or three years' imprisonment, or both. Persons in the government service were forbidden to use their official authority or influence to coerce the political action of anyone, or to interfere with elections.

Dorman B. Eaton, Leroy B. Thoman, and John M. Gregory were appointed commissioners by President Arthur. By the end of the year the new system was fairly in operation. Besides the departments at Washington, it applied to eleven customs districts and twenty-three post-offices where fifty or more officials were employed. The law could be thoroughly tested only when a new party came into power; that time was near at hand.

The deepest and most significant political movement of the last twenty years has been the gradual recovery of power by the Democracy. For some years after the Rebellion, this party's war record was a millstone around its neck. The financial distress in 1873 and the corruption prevalent in political circles weakened the party in power, while the Democracy, putting slavery and reconstruction behind its back, turned to new issues, and raised the cry of "economy" and "reform."

The state elections of 1874 witnessed a "tidal wave" of democratic victories. Out of 292 members of the House in 1875, 198 were democratic. Two-thirds of the Senators were still republican. Even by republican reckoning, the democratic presidential ticket in 1876 received a popular majority of 157,000 and lacked but one electoral vote. In 1879 both houses of Congress were democratic, by small majorities, for the first time since 1856. The tide ebbed in 1880, the Democrats losing control of the House, and suffering a decisive defeat in the presidential election; but with 1884 the fortune of the Democracy reached high-water mark.

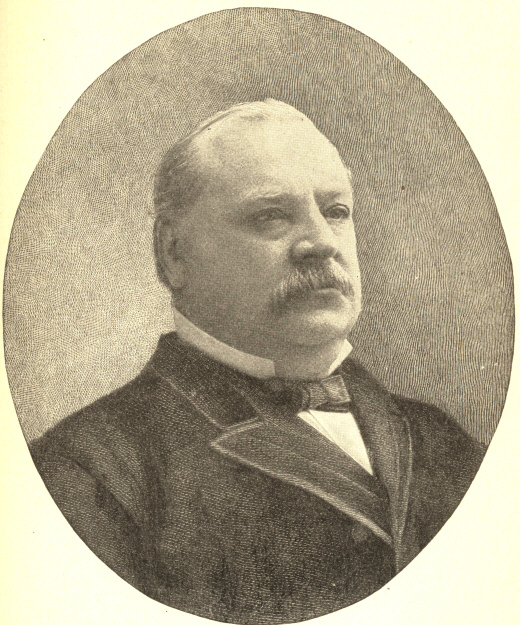

In this year James G. Blaine, of Maine, and John A. Logan, of Illinois, received the republican nomination for President and Vice-President. A number of Independent Republicans, including the most earnest advocates of civil service reform, were strongly opposed to Mr. Blaine, alleging him to be personally corrupt and the representative of corrupt political methods. They met in conference, denounced the nominations, and later indorsed the democratic nominees--Grover Cleveland, governor of New York, and Thomas A. Hendricks, of Indiana.

George W. Curtis, Carl Schurz, and other prominent Republicans took part in the movement. Several influential Independent Republican papers, including the New York Times, Boston Herald, and Springfield Republican, joined the bolt.

The campaign was bitterly personal, attacks upon the characters of the candidates taking the place of a discussion of principles. Mr. Cleveland was elected, receiving 219 electoral votes against 182 for Mr. Blaine. He carried every southern State, besides New York, Connecticut, Indiana, Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey. The total popular vote was over 10,000,000--the largest ever cast. Cleveland had 4,911,000, a plurality of 62,000 over Blaine. The Democrats regained control of the House in 1883, and held it by a considerable majority to the end of Mr. Cleveland's first term. In the Senate, until the election of 1892, the Republicans continued to have a small majority.

Grover Cleveland.

From a photograph copyrighted by C. M. Bell, Washington, D. C.

Upon the accession of the new administration to power, the country waited with deep interest to see its effect upon the civil service. Mr. Cleveland had pledged himself to a rigid enforcement of the new law, and encouraged all to believe that with him impartial civil service would not be confined to the few offices thus protected. After the first few months of Cleveland's administration, one fact was apparent: for the first time since the days of Jackson a change of the party in power had not been followed by a clean sweep among the holders of offices. But, as the subsequent record painfully shows, office-holders' pressure proved too strong for Mr. Cleveland's resolution.

There were then about 120,000 government employees. Of these, not far from 14,000 were covered by the Pendleton law. All the other minor places were held at the pleasure of superior officers. These latter officers numbered about 58,000. In August, 1887, from 45,000 to 48,000 of them had been changed, implying change in the offices dependent upon them.

There were some 55,000 postmasters, 2,400 of whom were appointed by the President for a term of four years, the rest by the postmaster-general at pleasure. At the date named, from 37,000 to 47,000 changes had been made in this department. These changes, of course, were not all removals, as many vacancies occur by expiration of terms, death of incumbents, and other causes.

An important statute regarding the presidential succession, introduced by Senator Hoar, passed Congress in January, 1886. By previous statutes, in case of the removal, death, resignation, or disability of the President and Vice-President, the presidency passed in order to the temporary President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House. The latter two might be of the opposite party from the President's, so that by the succession of either the will of the people as expressed in the presidential election would manifestly be defeated. Moreover, in case of a President's death and the accession of the Vice-President, the latter, too, might die, and thus both the presidency and the vice-presidency become vacant in the interim between two Congresses, when there is neither President of the Senate nor Speaker of the House.

Thus President Garfield died September 19, 1881, and the XLVlllth Congress did not convene to choose a Speaker until the next December. The Senate had adjourned without electing a presiding officer. Had President Arthur died at any moment during the intervening period--and it is said that he was for a time in imminent danger of death--the distracting contingency just spoken of would have been upon the country.

According to the new law, in case of a vacancy in both presidency and vice-presidency, the presidency devolves upon the members of the cabinet in the historical order of the establishment of their departments, beginning with the Secretary of State. Should he die, be impeached, or disabled, the Secretary of the Treasury would become President, to be followed in like crisis by the Secretary of War, he by the Attorney-General, he by the Postmaster-General, he by the Secretary of the Navy, he by the Secretary of the Interior, and he by the Secretary of Agriculture.

We have still no legal or official criterion of a President's disability. We do not know whether, during Garfield's illness, for instance--apparently a clear case of disability--it was proper for his cabinet to perform his presidential duties, or whether Arthur should not have assumed these. Barring this chance for conflict, it is not easy to think of an emergency in which the chief magistracy can now fall vacant, or the appropriate incumbent thereof be in doubt.