1840-1860 Chapter IV CALIFORNIA AND COMPROMISE OF 1850

CHAPTER IV.

CALIFORNIA AND THE COMPROMISE OF 1850

One of the campaigns at the beginning of the Mexican War was that of General Stephen W. Kearney, from Fort Leavenworth, against New Mexico. It was opened in May, 1846. He invaded the country without much opposition, arrived at Santa Fe August 18th, having marched 873 miles, declared the inhabitants free from all allegiance to Mexico, and formed a territorial government over them as United States subjects.

Captain John C. Fremont had previously, but in the same year, 1846, been sent to California at the head of an exploring expedition, and in May he was notified to remain in the country in anticipation of hostilities. On June 15th he captured Samona. Meanwhile, Commodore Sloat was erecting our flag over the towns on the coast.

Zachary Taylor.

After a photograph by Brady.

In July Sloat was superseded by Commodore Stockton, who routed the Mexican commander, De Castro, at Los Angeles, joined Fremont, and on August 13th seized Monterey, the then capital. The two commanders now placed themselves at the head of a provisional government for California.

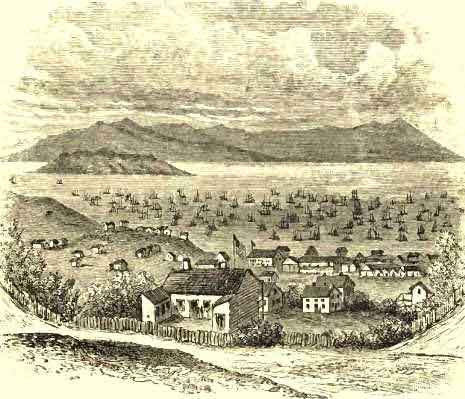

The Site of San Francisco in 1848.

In 1848, on the same day and almost at the same hour when the peace of Guadalupe Hidalgo was concluded, gold was discovered in California. It was on the land of one Sutter, a Swiss settler in the Sacramento Valley, as some workmen were opening a flume for a mill. In three months over 4,000 persons were there, digging for gold with great success. By July, 1849, it is thought, 15,000 had arrived. Nearly all were forced to live in booths, tents, log huts, and under the open sky.

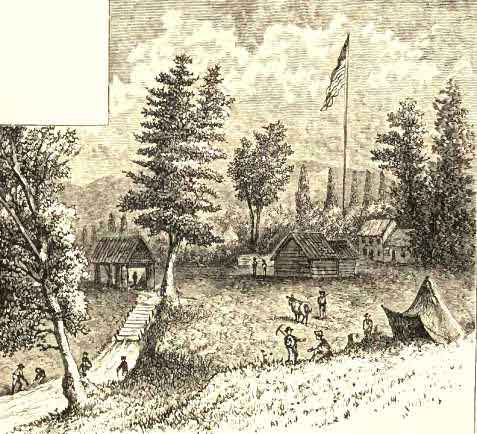

Sutter's Mill, California, where Gold was First Discovered.

The sparse population previously on the ground left off farming and grazing and opened mines. People became insane for gold. Immigrants soon came in immense hordes. In 1846, aside from roving Indians, California had numbered not much over 15,000 inhabitants. By 1850, it seems certain that the territory contained no fewer than 92,597. The new-comers were from almost every land and clime--Mexico, South America, the Sandwich Islands, China--though, of course, most were Americans. The bulk of these hailed from the Northwest and the Northeast. To this land of promise the sturdy pioneers from the Mississippi Valley found their way on foot, on horseback, or in wagons, over the Rocky Mountains and the Sierras, following trails previously untrodden by civilized man. Those from the East made long detours around Cape Horn or across the Isthmus of Panama.

The yield of gold from the virgin placers was enormous, a laborer's average the first season being perhaps an ounce a day, though many made much more. During the first two years about $40,000,000 worth of gold was extracted. According to careful estimates the gold yield of the United States, mostly from California, which had been only $890,000 in 1847, increased to $10,000,000 in 1848, to $40,000,000 in 1849, to $50,000,000 in 1850, to $55,000,000 in 1851, to $60,000,000 in 1852, and in 1853 to $65,000,000.

Most interesting were the spontaneous governmental and legal institutions which arose in these motley communities, some of them finding their originals in the English mining districts, others in Mexico and Spain, and still others recalling the mining customs of medieval Germany. For a time many camps had each its independent government, disconnected from all human authority around or above. Some of these were modelled after the Mexican Alcaldeship, others after the New England town. Over those who rushed to the vicinity of Sutter's mill that gentleman became virtual Alcalde, though he was not recognized by all.

The men first opening a placer would seek to pre-empt all the adjoining land, giving up only when others came in numbers too strong for them. Officers were elected and new customs sanctioned as they were needed. Partnerships were sacredly maintained, yet by no other law than that of the camp. Crimes against property and life seem to have been infrequent at first, but the unparalleled wealth toled in and developed a criminal class, which the rudimentary government could not control. San Francisco formed in 1851 a vigilance committee of citizens, by which crimes could be more summarily and surely punished. The pioneer banking house in California began business at San Francisco in January, 1849. The same month saw the first frame house on the Sacramento, near Sutter's Fort.

The vast acquisition of territory by the Mexican War seemed destined to be a great victory for slavery, because nearly all of it lay south of 36 degrees 30 minutes and hence by the Missouri Compromise could become slave soil.

But there was the complication that under Mexico all this wide realm had been free. To exist there legally slavery must therefore be established by Congress, making the case very different from the cases of Louisiana, Florida, and Texas, which came under United States authority already burdened. This predisposed many who were not in general opposed to slavery, against extending the institution hither. Early in the war a bill had passed the House, failing almost by accident in the Senate, which contained the famous Wilmot Proviso, so named from its mover in the House, that, except for crime, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude should ever exist in any of the territories to be annexed. Wilmot was a Democrat, and at this time a decided majority of his party favored the proviso. But the pro-slavery wing rallied, while the Whigs, disbelieving in the war and in annexation both, offered the proviso Democrats no hearty aid. In consequence it was defeated both then and after the annexation.

The election of 1848 went for the Whigs, and the next March 4th, General Taylor became President. Though a southerner and a slave-holder, he was moderate and a true patriot. So rapid had been the influx into California that the Territory needed a stable government. Accordingly, one of Taylor's first acts as President was to urge California to apply for admission to statehood. General Riley, military governor, at once called a convention, which, sitting from September 1st to October 13th, framed a constitution and made request that California be taken into the Union. This constitution prohibited slavery, and thus a new firebrand was tossed into the combustible material with which the political situation abounded. By this time nearly all the friends of freedom were for the proviso, but its enemies as well had greatly increased. The immense growth, actual and prospective, of northern population, greatly inspired one side and angered the other.

Resort was now had again to the old, illusive device of compromise, Clay being the leader as usual. He brought forward his "Omnibus Bill," so called because it threw a sop to everybody. It failed to pass as a single measure, but was broken up and enacted piecemeal. Stubborn was the fight. Radicals of the one part would consent to nothing short of extending the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific; those of the other stood solidly for the unmodified proviso.

In this crisis occurred President Taylor's death, July 9, 1850, which was most unfortunate. He was known not to favor the pro-slavery aggression which, in spite of Clay's personal leaning in the opposite direction, the omnibus bill embodied. Mr. Fillmore, as also Webster, whom he made his Secretary of State, nervous with fear of an anti-slavery reputation, went fully Clay's length. The debate on this compromise of 1850 was the occasion when Webster deserted the free-soil principles which were now dominant in New England. His celebrated speech of March. 7th marked the crisis of his life. He argued that the proviso was not needed to prevent slavery in the newly gotten district, while its passage would be a wanton provocation to the South.

COMPROMISE OF 1850 209

From this moment Massachusetts dropped him. When she next elected a senator for a full term, it was Charles Sumner, candidate of the united Democrats and Free-soilers, who went to Congress pledged to fight slavery to the death.

But the omnibus compromises were passed. California was, indeed, admitted free, September 9, 1850--the thirty-first State in order--and slave-trade in the District of Columbia slightly alleviated. On the other hand, Texas was stretched to include a huge piece of New Mexico that was free before, and paid $10,000,000 to relinquish further claims. This was virtually a bonus to holders of her scrip, which from seventeen cents the dollar instantly rose to par. New Mexico and Utah were to be organized as Territories without the proviso, and were made powerless to legislate on slavery till they should become States.

VOL. III.--14

Least sufferable, a fugitive slave law was passed, so Draconian that that of 1793, hitherto in force, was benign in comparison. It placed the entire power of the general Government at the slave-hunter's disposal, and ordered rendition without trial or grant of habeas corpus, on a certificate to be had by simple affidavit. Bystanders, if bidden, were obliged to help marshals, and tremendous penalties imposed for aid to fugitives.

This act facilitated the recovery of fugitives at first, but not permanently. Many who had labored for its passage soon saw that it was a mistake. It powerfully fanned the abolition flame all over the North. New personal liberty laws were enacted. A daily increasing number adopted the view that the new act was unconstitutional, on the ground that the Constitution places the rendition of slaves as of criminals in the hands of States, and guarantees jury trial, even upon title to property, if over twenty dollars in value. After the act had been justified in the courts, multitudes of moderate northern men urged to a dangerous degree the doctrine of state rights in defence of the liberty laws.

Millard Fillmore.

From a painting by Carpenter in 3, at the City Hall, New York.

Others adopted the cry of the "higher law," and without joining Garrison in denouncing the Government, did not hesitate to oppose in every possible way the operation of this drastic legislation for slave-catching. .

The country's growth made escape from bondage continually easier and easier. Once across the border a runaway was sure to find many friends and few enemies. Openly, or, if this was required, by stealth, he was passed quickly along to the Canada line. Between 1830 and 1860 over 30,000 slaves are estimated to have taken refuge in Canada. By 1850, probably no less than 20,000 had found homes in the free States. The new law moved many of these across into the British dominions. It was hence increasingly difficult for the slave-owner to recover stray property. All possible legal obstructions were placed in his way, and when these failed he was likely still to be opposed by a mob which might prove too powerful for the marshal and any posse which he could gather.

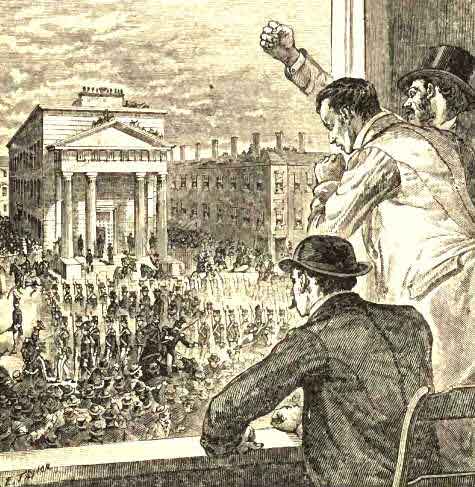

The Rendition of Anthony Burns in Boston.

In Boston, when a slave named Shadrach was arrested, his friends made a sudden dash, rescued him from the officers and freed him. With Simms the same was attempted, but in vain.

The removal of Anthony Burns from that city in 1855 was possible only by escorting him down State Street to the revenue cutter in waiting, inside a dense hollow square of United States artillerymen and marines, with the whole city's militia under arms and at hand. Business houses as well as residences were closed and draped in mourning. It was an indignity which Massachusetts never forgot. At Alton, Ill., slave-hunters seized a respectable colored woman, long resident there, who fully believed herself free. She was surrounded by an infuriated company of citizens, and would have been wrenched from her captors' clutch had not they, in their terror, offered to sell her back into freedom. The needed $1,200 was raised in a few minutes, and the agonized creature restored to her family. Judge Davis, whom the evidence had compelled to deliver the woman, on rendering the sentence resigned his commission, declaring: "The law gives you your victim. Thank it and not me, and may God have mercy on your sinful souls."