1840-1860 Chapter III THE MEXICAN WAR

CHAPTER III.

THE MEXICAN WAR

Attracted by fertility of soil and advantages for cattle-raising, large numbers of Americans had long been emigrating to Texas. By 1830 they probably comprised a majority of its inhabitants. March 2, 1836, Texas declared its independence of Mexico, and on April 10th of that year fought in defence of the same the decisive battle of San Jacinto. Here Houston gained a complete victory over Santa Anna, the Mexican President, captured him, and extorted his signature to a treaty acknowledging Texan independence. This, however, as having been forced, the Mexican Government would not ratify.

Not only did the Texans almost to a man wish annexation to our Union, but, as we have seen, the dominant wing of the democratic party in the Union itself was bent upon the same, forcing a demand for this into their national platform in 1840. Van Buren did not favor it, which was the sole reason why he forfeited to Polk the democratic nomination in 1844.

General Sam. Houston.

Polk was elected by free-soil votes cast for Birney, which, had Clay received them, would have carried New York and Michigan for him and thus elected him; but the result was hailed as indorsing annexation. Calhoun, Tyler's Secretary of State, more influential than any other one man in bringing it about, therefore now advocated it more zealously than ever.

Calhoun's purpose in this was to balance the immense growth of the North by adding to southern territory Texas, which would of course become a slave State, and perhaps in time make several States. As the war progressed he grew moderate, out of fear that the South's show of territorial greed would give the North just excuse for sectional measures.

Henry Clay, with nearly the entire Whig Party, from the first opposed the TylerCalhoun programme. Clay's own reason for this, as his memorable Lexington speech in 1847 disclosed, was that the United States would be looked upon "as actuated by a spirit of rapacity and an inordinate desire for territorial aggrandizement." His party as a whole dreaded more the increment which would come to the slave power. After much discussion in Congress, Texas was annexed to the Union on January 25, 1845, just previous to Polk's accession. June 18th, the Texan Congress unanimously assented, its act being ratified July 4th by a popular convention. Thus were added to the United States 376,133 square miles of territory.

General Santa Anna.

The all-absorbing question now was where Texas ended: at the Nueces, as Mexico declared, or at the Rio Grande, as Texas itself had maintained, insisting upon that stream as of old the bourne between Spanish America and the French Louisiana. Mexico, proud, had recognized neither the independence of Texas nor its annexation by the United States, yet would probably have agreed to both as preferable to war, had the alternative been allowed.

To be sure, she was dilatory in settling admitted claims for certain depredations upon our commerce, threatened to take the annexation as a casus belli, withdrew her envoy and declined to accept Slidell as ours, and precipitated the first actual bloodshed. Yet war might have been averted, and our Government, not Mexico's, was to blame for the contrary result. Slidell played the bully, the navy threatened the coast, our wholly deficient title, through Texas, to the Nueces-Rio-Grande tract was assumed without the slightest ado to be good, and when General Arista, having crossed the river in Taylor's vicinity, repelled the latter's attack upon him, the President, followed by Congress, falsely alleged war to exist "by act of the Republic of Mexico."

During most of 1845, General Zachary Taylor was at Corpus Christi on the west bank of the Nueces, in command of 3,600 men. The first aggressive movement occurred in March of the following year, when Taylor, invading the disputed territory by command from Washington, advanced to the Rio Grande, opposite Matamoras. April 26th, a Mexican force crossed the river and captured a party of American dragoons which attacked them. Taylor drew back to establish communication with Point Isabel, and on advancing again toward the Rio Grande, May 8th, found before him a Mexican force of nearly twice his numbers, commanded by Arista. The battle of Palo Alto ensued, and next day that of Resaca de la Palma, Taylor completely victorious in both. May 13th, before knowledge of these actions had reached Washington, warranted merely by news of the cavalry skirmish on April 26th, Congress declared war, and the President immediately called for 50,000 volunteers. In July Taylor was re-enforced by Worth, and proceeded to organize a campaign against Monterey, a strongly fortified town some ninety miles toward the City of Mexico. This place was reached September 19th, and captured on the 22d, after hard fighting and severe losses on both sides. An armistice of eight weeks followed.

James K. Polk

After a photograph by Brady.

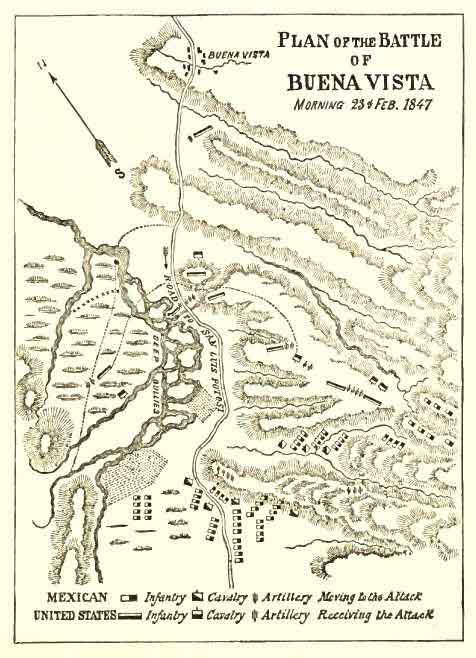

PLAN OF THE BATTLE OF BUENA VISTA

MORNING 23 OF FEB 1847.

Meantime a revolution had occurred in Mexico. The banished Santa Anna was recalled, and as President of the Republic assumed command of the Mexican armies. On February 23, 1847, occurred one of the most sanguinary but brilliant battles of the war, that of Buena Vista. Taylor, learning that a Mexican force was advancing under Santa Anna, at least double the 5,200 left him after the requisition upon him which General Scott had just made, drew back to the strong position of Buena Vista, south of Saltillo. Here Santa Anna, having through an intercepted despatch learned of Taylor's weakness, ferociously fell upon him with a force 12,000 strong. On right and centre, by dint of good tactics and bull-dog fighting, Taylor held his own and more, but the foe succeeded at first in partly turning and pushing back his left. The Mexican commander bade Taylor surrender, but was refused, whence the saying that "Old Rough and Ready," as they called Taylor, "was whipped but didn't know it."

To check the flanking movement he sent forward two regiments of infantry, well supported by dragoons and artillery, who charged the advancing mass, broke the Mexicans' column, and sent them fleeing in confusion. This saved the day.

General Winfield Scott.

The American loss was 746, including several officers, among them Lieutenant-Colonel Clay, son of the Kentucky statesman. Colonel Jefferson Davis, one day to be President of the Southern Confederacy, caused during this conflict great havoc in the enemy's ranks with his Mississippi riflemen. Santa Anna's loss was 2,000.

General Winfield Scott had meantime been ordered to Mexico as chief in command. Taylor was a Whig, and the Whigs whispered that his martial deeds were making the democratic cabinet dread him as a presidential candidate. But Scott was a Whig, too, and if there was anything in the surmise, his victorious march must have given Polk's political household additional food for reflection. Scott's plan was to reduce Vera Cruz, and thence march to the Mexican capital, two hundred miles away, by the quickest route. Vera Cruz capitulated March 27, 1847.

Scott straightway struck out for the interior. He was bloodily opposed at Cerro Gordo, April 18th, and at Jalapa, but he made quick work of the enemy at both these places. In the latter city, after his victory, he awaited promised re-enforcements. When the last of these had arrived, August 6th, under General Franklin Pierce, so that he could muster about 14,000 men, he advanced again.

August 10th the Americans were in sight of the City of Mexico. This was a natural stronghold, and art had added to its strength in every possible way. Except on the south and west it was nearly inaccessible if defended with any spirit. Scott of course directed his attack toward the west and south sides of the city. The first battle in the environs of the capital was fiercely fought near the village of Contreras, and proved an overwhelming defeat for the Mexicans. Two thousand were killed or wounded, while nearly 1,000, including four generals, were captured, together with a large quantity of stores and ammunition. The American loss was only 60 killed and wounded.

The survivors fled to Churubusco, farther toward the city, where, with every advantage of position, Santa Anna had united his forces for a final stand. An old stone convent, which our artillery could not reach till late in the action, was utilized as a barricade, and from this the Mexicans poured a most deadly fire upon their assailants.

The Americans were victorious, as usual, but their loss was fearful, 1,000 being killed or wounded, including 76 officers. A truce to last a fortnight was now agreed upon, but Scott, seeing that the Mexicans were taking advantage of it to strengthen their fortifications, did not wait so long. He now had about 8,500 men fit for duty, and sixty-eight guns. Hostilities were renewed September 7th, by the storm and capture, costing nearly 800 men, of Molino del Rey, or "King's Mill," a mile and a half from the city.

Possession of the Molino opened the way to Chapultepec, the Gibraltar of Mexico, 1,100 yards nearer the goal. As it was built upon a rock 150 feet high, impregnable on the north and well-nigh so on the eastern and most of the southern face, only the western and part of the southern sides could be scaled. But the stronghold was the key to the city, and after surveying the situation, a council of war decided that it must be taken.

The Plaza of the City of Mexico.

Two picked American detachments, one from the west, one from the south, pushed up the rugged steeps in face of a withering fire. The rock-walls to the base of the castle had to be mounted by ladders.

VOL. III.--13

This was successfully accomplished; the enemy were driven from the building back into the city, and the castle and grounds occupied by our troops. A large number of fugitives were cut off by a force sent around to the north.

To pierce the city was even now by no means easy. The approach was by two roads, one entering the Belen gate, the other the San Cosme. General Quitman advanced toward the Belen, but at the entrance was stopped by a destructive cannonade from the citadel itself. Those fighting their way toward the San Cosme succeeded in entering the city, Lieutenant U. S. Grant making his mark in the gallant work of this day. The city was evacuated that night, and on the 15th of September, 1847, was fully in the hands of Scott.

The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848. It established the Rio Grande as the boundary between the two countries, and New Mexico, of course including what is now Arizona and also California, was ceded to the United States for $15,000,000.

The United States also assumed, to the sum of $3,250,000, the claims of American citizens upon Mexico. For Gadsden's Purchase, in 1853, between the Gila River and the Mexican State of Chihuahua, we paid $10,000,000 more. Our territory thus received in all, as a consequence of the Mexican War, an increment of 591,398 square miles.

Inseparable from the politics of the Mexican War is the Oregon question, since Oregon's re-occupation and "fifty-four forty or fight" had been democratic cries for securing to Polk west-northern votes in 1844. We had, however, no valid claim so far north, except against Russia--by the treaty of 1824. The Louisiana purchase, indeed, had vested us with whatever--very dubious--rights France had upon the Pacific, and the Florida treaty of 1819 gave us the far better title of Spain to the coast north of 42 degrees.

196 SLAVERY CONTROVERSY

This treaty, with Gray's discovery of the Columbia in 1792, Lewis and Clarke's official explorations of the Columbia valley in 1804-05-06, England's retrocession, in 1818, of Astoria, captured during the War of 1812, and extensive actual settlements upon the river by American citizens from 1832 on, made our claim perfect up to 49 degrees at least. This parallel the convention with Great Britain in 1818 had already fixed as our northern line from the Lake of Woods to the Rocky Mountains. Between this and 54 degrees 40 minutes, England's title, from exploration and settlement, was superior to ours, which was based upon alleged old Spanish discovery. The same convention of 1818, renewed in 1827, opened the Oregon country to occupation by settlers from both nations. Increase of immigration rendering a fixing of jurisdictions imperative, England pressed for the line of the Columbia below its intersection of the forty-ninth parallel. We had twice offered to settle upon 49 degrees, which limit the rapid growth of our population in the region induced England in 1836 to accept.

THE MEXICAN WAR 197

Whether Polk's blustering demand for "all Oregon," which came near bringing on war with England, and his much condemned recession later, were mere opportunist acts, is still a question. Many consider them pieces of a deep-laid policy by Polk to tole Mexico to war in hope of England's aid, then, suddenly pacifying England, to devour Mexico at his leisure.