1840-1860 Chapter II "IMMEDIATE ABOLITION"

CHAPTER II.

"IMMEDIATE ABOLITION"

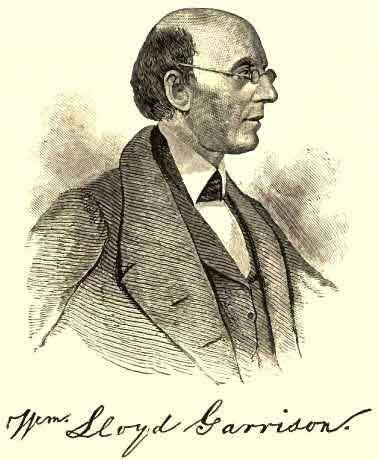

While slavery was thus strengthening itself upon its own soil and in some respects also at the North, its champions ever more alert and forward, its old foes asleep, these very facts were provoking thought about the institution and hostility to it, destined in time to work its overthrow. Interested people saw that slavery, so aggressive and defiant, must be fought to be put down, and that if the Constitution was its bulwark, as all believed, provided a tithe of what the South as well as the North had said of its evils was true, the whole country, and not the South only, was guilty in tolerating the curse. In 1821 Lundy began publishing his Genius of Universal Emancipation, seconded, from 1829, by the more radical Garrison.

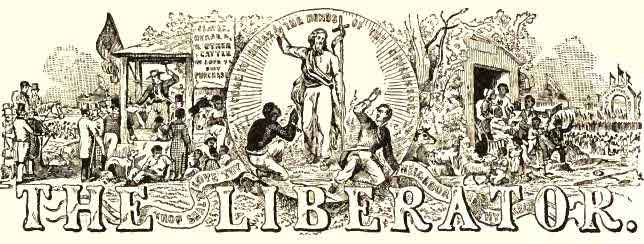

In 1831 Garrison founded the Liberator, whose motto, "immediate and unconditional emancipation," was intended as a rebuke to the tame policy of the colonizationists. "I am in earnest," said the plucky man, when his utterances threatened to cost him his life, "I am in earnest, I will not equivocate, I will not excuse, I will not retreat a single inch, and I will be heard." These were startling tones. Had God turned a new prophet loose in the earth?

The abolition spirit was a part of the general moral and religious quickening we have mentioned as beginning about 1825, and revealing itself in revivals, missions, a religious press, and belief in the end of the world as approaching. The ethical teaching of the great German philosopher, Emanuel Kant, denouncing all use of man as an instrument, began to take effect in America through the writings of Coleridge. Hatred of slavery was gradually intensified and spread. In 1832 rose the New England Anti-Slavery Society. In 1833 the American Society was organized, with a platform declaring "slavery a crime."

John G. Whittier in 1833.

This declaration marked one of the most important turning-points in all the history of the United States. It drew the line. It brought to view the presence in our land of two sets of earnest thinkers, with diametrically opposite views touching slavery, who could not permanently live together under one constitution.

May, Phillips, Weld, Whittier, the Tappans, and many other men of intellect, of oratorical power, and of wealth, drew to Garrison's side. State abolition societies were organized all over the North, the Underground Railroad was hard worked in helping fugitives to Canada, and fiery prophets harangued wherever they could get a hearing, demanding "immediate abolition" in the name of God.

The Abolitionists proposed none but moral arms in fighting slavery--papers, pamphlets, public addresses, personal appeals. They deprecated rebellion by slaves, and urged congressional action against slavery only in the District of Columbia, in the territories, and at sea, where the absolute jurisdiction of the general Government was admitted by nearly all. Nevertheless, southern hostility to them was indescribably ferocious and uncompromising. They were charged with instigating all the slave insurrections and insubordination that occurred, and with having made necessary the new, more diabolical discipline over blacks, both bond and free.

Southern papers and Legislatures incessantly commanded that Abolitionists be delivered up to southern justice, their societies and their publications suppressed by law, and abolitionist agitation made penal.

Wm. Lloyd Garrison.

There were northerners quite ready to grant these demands. Rage against abolitionism, much of it, if possible, even more unreasoning, prevailed at the North.

Garrison says that he found here "contempt more bitter, detraction more relentless, prejudice more stubborn, and apathy more frozen than among slave-owners themselves." The Church, politics, business--all interests save righteousness--seemed to bow to the false god. Of all utterances against abolitionism, those of clergymen and religious journals were the bitterest. To call slavery sin was the unpardonable sin.

In 1834, on July 4th, a mob broke up a meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York. A few days after, Lewis Tappan's house was sacked in the same manner, as well as several churches, school-houses, and dwellings of colored families. At Newark, N. J., a colored man who had been introduced into a pulpit by the minister of the congregation, was forcibly wrenched therefrom and carried off to jail. The pulpit was then torn down and the church gutted. In Norwich, Conn., the mob pulled an abolitionist lecturer from his platform and drummed him out of town to the Rogues' March.

In 1836 occurred the murder of Rev. E. P. Lovejoy, at Alton, Ill. He was the publisher of The Observer, an abolitionist sheet, which had already been three times suspended by the destruction of his printing apparatus. It was at a meeting held in Faneuil Hall over this occurrence that Wendell Phillips first made his appearance as an anti-slavery orator.

Wendell Phillip.

Also in 1836 the office at Cincinnati in which James G. Birney published The Philanthropist, was sacked, the types scattered, and the press broken and sunk in the river. Birney was a southerner by birth, and had been a slave-holder, but had freed his slaves. Between 1834 and 1840 there was hardly a place of any size in the North where an Abolitionist could speak with certain safety.

The destruction of colored people's houses became for a time an every-day occurrence in many northern cities. For some years the condition of the free blacks and their friends was hardly better north than south. Schools for colored children were violently opposed even in New England. One kept by Miss Prudence Crandall, at Canterbury, Conn., was, after its opponents had for months sought in every manner to close it, destroyed by fire. The lady herself was imprisoned, and such schools were by law forbidden in the State. A colored school at Canaan, N. H., was voted a nuisance by a meeting of the town; the building was then dragged from its foundations and ruined. Many who aided in these deeds belonged to what were regarded the most respectable classes of society.

Owing to the vagaries and unpatriotism of the Garrisonians, there was from 1840 schism in the abolition ranks. Garrison and his closest sympathizers were very radical on other questions besides that concerning the sin of slavery. They declared the Constitution "a league with death and a covenant with hell" because it recognized slavery. They would neither vote nor hold office under it. They upbraided the churches as full of the devil's allies. They also advocated community of property, women's rights, and some of them free love. Others, as Birney, Whittier, and Gerrit Smith, refused to believe so ill of the Constitution or of the churches, and wished to rush the slavery question right into the political arena. The division, far from hindering, greatly set forward the abolitionist cause.

Perhaps neither abolition society, as such, had, after the schism of 1840, quite the influence which the old exerted at first, but by this time a very general public opinion maintained anti-slavery propagandism, pushing it henceforth more powerfully than ever, as well as, through broader modes of utterance and action, more successfully. Whittier, Lowell, Longfellow, each enlisted his muse in the crusade. Wendell Phillips's tongue was a flaming sword. Clergymen, politicians, and other people entirely conservative in most things, felt free to join the new society of political Abolitionists.

In 1839 the Governor of Virginia made a requisition on Governor Seward of New York, to send to Virginia three sailors charged with having aided a slave out of bondage. Seward declined, on the ground that by New York law the sailors were guilty of no crime, as that law knew nothing of property in man. He accompanied his refusal with a discussion of slavery and slave law quite in the abolitionist vein. To a like call from Georgia, Seward responded in the same way, and his example was followed by other northern governors.

The Liberty Party took the field in 1840, Birney and Earle for candidates, who polled nearly 7,000 votes. Four years later Birney and Morris received 62,300.

It would be a mistake, let us remember, to regard the anti-abolitionist temper at the North wholly as apathy, friendliness to slavery, or the result of truckling to the South. Besides sharing the general fanaticism which mixed itself with the movement, the Abolitionists ignored the South's dilemma--the ultras totally, the moderates too much. "What would you do, brethren, were you in our place?" asked Dr. Richard Fuller, of Baltimore, in a national religious meeting where slavery was under debate; "how would you go to work to realize your views?" Dr. Spencer H. Cone, of New York, roared in reply, "I would proclaim liberty throughout all the land, to all the inhabitants thereof." But the thing was far from being so simple as that. Denouncing the Constitution as Garrison did could not but affront patriotic hearts. It was impolitic, to say the least, to import English co-agitators, who could not understand the intricacies of the subject as presented here.

facsimile of Heading of the "Liberator."

The fact that, defying slave-masters and sycophants alike, the cause of abolition still went on conquering and to conquer, was due much less to the strength of its arguments and the energy of its agitation than to the South's wild outcry and preposterous effrontery of demand. Conservative northerners began to see that, bad as abolitionism might be, the means proposed for its suppression were worse still, being absolutely subversive of personal liberty, free speech, and a free press.

More serious was the conviction, which the South's attitude nursed, that such mortal horror at Abolitionists and their propaganda could only be explained by some sort of a conviction on the part of the South itself that the Abolitionists were right, and that slavery was precisely the heinous and damnable evil they declared it to be. It was mostly in considering this aspect of the case that the Church and clergy more and more developed conscience and voice on freedom's side, as practical allies of abolitionism. In each great denomination the South had to break off from the North on account of the latter's love to the black as a human being. Men felt that an institution unable to stand discussion ought to fall. By 1850 there were few places at the North where an Abolitionist might not safely speak his mind.

It were as unjust as it would be painful to view this long, courageous, desperate defence of slavery as the pure product of depravity. The South had a cause, in logic, law, and, to an extent, even in justice. Both sides could rightly appeal to the Constitution, the deep, irrepressible antagonism of freedom against bondage having there its seat. The very existence of the Constitution presupposed that each section should respect the institutions of the other. What right, then, had the North to allow publications confessedly intended to destroy a legal southern institution, deeply rooted and cherished? From a merely constitutional point of view this question was no less proper than the other: What right had the South, among much else, to enact laws putting in prison northern citizens of color absolutely without indictment, when, as sailors, they touched at southern ports, and keeping them there till their ships sailed? This outrage had occurred repeatedly. What was worse, when Messrs. Hoar and Hubbard visited Charleston and New Orleans, respectively, to bring amicable suits that should go to the Supreme Court and there decide the legality of such detention, they were obliged to withdraw to escape personal violence.

It was said that the North must bear these incidents of slavery, so obnoxious to it, in deference to our complex political system. Yes, but it was equally the South's duty to bear the, to it, obnoxious incidents of freedom. Southern men seem never to have thought of this. Doubtless, as emancipation in any style would have afflicted it, the South could not but account all incitements thereto as hardships; but the North must have suffered hardships, if less gross and tangible, yet more real and galling, had it acceded to southern wishes touching liberty of person, speech, and the press. That at the North which offended the South was of the very soul and essence of free government; that at the South which aggrieved the North was, however important, certainly somewhat less essential. Manifestly, considerations other than legal or constitutional needed to be invoked in order to a decision of the case upon its merits, and these, had they been judicially weighed, must, it would seem, all have told powerfully against slavery.

VOL. III.--12

Not to raise the question whether the black was a man, with the inalienable rights mentioned in the Declaration of Independence, the South's own economic and moral weal, and further--what one would suppose should alone have determined the question--its social peace and political stability loudly demanded every possible effort and device for the extirpation of slavery. That this would have been difficult all must admit; that it was intrinsically possible the examples of Cuba and Brazil since sufficiently prove.