1860-1868 Chapter XI RECONSTRUCTION

CHAPTER XI.

RECONSTRUCTION

Though arms were grounded, there remained the new task, longer and more perplexing, if not more difficult, than the first, of restoring the South to its normal position in the Union. It was, from the nature of the case, a delicate one. The proud and sensitive South smarted under defeat and was not yet cured of the illusions which had led her to secede. Salve and not salt needed to be rubbed in to her wounds. The North stood ready to forgive the past, but insisted, in the name of its desolate homes and slaughtered President, that the South must be restored on such conditions that the past could never be repeated. The difficulty was heightened by the lack of either constitutional provision or historical precedent. Not strange, therefore, that the actors in this new drama of reconstruction played their parts awkwardly and with many mistakes.

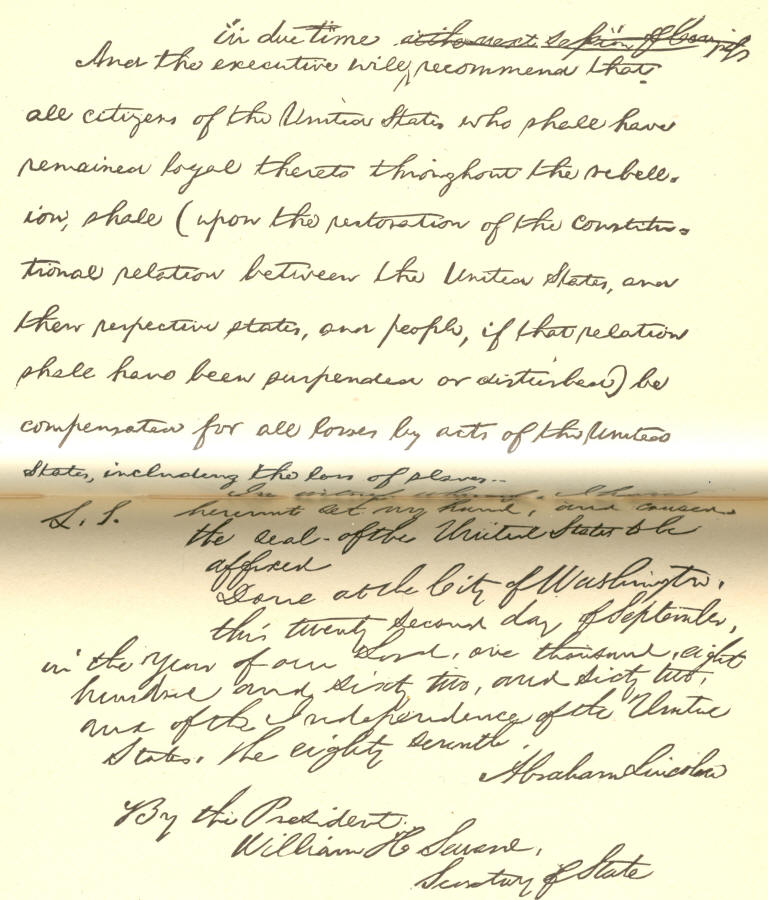

Facsimile of a portion of President Lincoln's draft of the

Preliminary Proclamation of Emancipation, September. 1862

From the original in the Library of the State of New York, Albany.

A most interesting constitutional problem had to be faced at the outset: What effect had secession had upon the States guilty of it; was it or was it not an act of state suicide? This question was warmly debated in Congress and out. Although ridiculed in some quarters as a mere metaphysical quibble, it lay at the bottom of men's political thinking on reconstruction, and their views of the proper answer to it powerfully influenced their action.

All loyal Democrats and most Republicans answered it in the negative. Secession, they said, being an invalid act, had no effect whatever; the rebellious tracts were still States of the Union in spite of themselves. But the two parties reasoned their way to this conclusion by different roads. The Democrats deduced the view from the State's intrinsic sovereignty, the Republicans from the national Constitution as ordaining "an indestructible Union of indestructible States." This class of thinkers, in whichever party they were found, naturally preferred the term "restoration" to "reconstruction."

The theory of state suicide was held by many, but with a difference. Sumner and a few others deemed that secession had destroyed statehood alone; that over individuals the Constitution still extended its authority and its protection, as in Territories. Thaddeus Stevens and his followers viewed secession as having left the State not only defunct but a washed slate governmentally, like soil won by conquest. Both these parties conceived the work before Congress to be out-and-out "reconstruction," involving the right to change old state lines and institutions at will. Not even this position was more ultra than the course which reconstruction actually took.

Closely related to this main problem were several other questions nearly or quite as vexing. Were any conditions to be imposed upon the peoples seeking re-admission to the Union as States? If so, what, aside from the loyalty of voters and officeholders, were these conditions? Was the President to initiate and oversee the process of redintegration, prescribing the conditions of re-admission, and determining when they were fulfilled, or was all this the business of Congress? And, lastly, did the right thus to oversee and impose conditions depend upon a certain war power of Congress or of President, or upon the clause of the Constitution which guarantees to every State a republican form of government? Nearly the same question as this, in another form, would be, Was this right explicitly constitutional or only impliedly so?

The answer practically returned to these difficult inquiries was that Congress, as a quasi war right, must exact of the States lately in secession all the conditions necessary, in its view, to their permanent loyalty and the peace of the Union.

The history of reconstruction divides into three periods: Reconstruction during the war, President Johnson's work, and Congressional reconstruction.

Restoration was the universal thought at first. Congressional resolutions in 1861 declared that the war was not waged "for the purpose of overthrowing or interfering with the rights or established institutions" of the seceding States. Their action was looked upon as an insurrection against the state government as well as against the United States. Accordingly, when a handful of Virginia loyalists, in the summer of 1861, formed a state government and elected national senators and representatives, President and Congress recognized them as the true State of Virginia.

Following out the same idea, President Lincoln proclaimed in 1863 that as soon as one-tenth of the voters of any seceded State would swear to abide by the Constitution and the emancipation laws they might form a state government. In this way Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee were reconstructed during 1863 and 1865.

The hand of the assassin removed Lincoln from the scene of action at a time when North and South alike stood most in need of his kind heart, tact, and firmness. Andrew Johnson succeeded to a task for which he was ill-fitted. Conceited, obstinate, and pugnacious, he began by alarming the South with threats of wholesale punishment for the "crime of treason," and ended by alienating his own party through his slack methods of re-establishing the States. Johnson declared, and no doubt honestly, that he was carrying out Lincoln's ideas. In May, 1865, he offered amnesty to all but certain excepted classes, mainly civil and military leaders, upon condition of an oath to support the Constitution, including its Thirteenth Amendment, forbidding slavery. Though the proclamation declaring this to be in force did not issue till December 18, 1865, it had been approved by Congress the preceding February.

President Johnson then proceeded to reorganize the state governments. For each seceded State, except the four already reconstructed, he appointed a provincial governor. The governor called a State convention. Only whites who had taken the amnesty oath could elect delegates, or themselves be elected, to this convention.

At the instance of the President the convention adopted a constitution or legislation which forbade slavery, declared the ordinance of secession null and void, and repudiated the Confederate debt. The convention then appointed times and places for the election of a legislature and a permanent governor. In a few months the governmental machinery had been set in motion in all the late Confederate States, and in December senators and representatives from all except Texas were knocking at the doors of Congress.

Thus far the President had had full sway. But upon the re-assembling of Congress in December, it became apparent that he and his party were not in harmony. Congress, still overwhelmingly republican, refused to admit the southern delegates, and appointed a committee to investigate the condition of affairs in the southern States. Its report was anything but re-assuring, and Congress, mainly under the lead of Thaddeus Stevens, boldly proceeded to rip up the entire presidential work.

Several considerations led Congress to this course. They denied the President's right, on his own sole authority, to re-establish permanent governments in the States in question. Furthermore, the new state governments were declared unlawful because their constitutions had not been submitted to the people for ratification. Congress also maintained that only the law-making power could of right determine the conditions of re-admission to the Union, and judge whether or not those conditions had been fulfilled.

But the consideration which outweighed all others in favor of the congressional procedure was the alarming temper and acts of the South itself. The Carolinas and Georgia had simply repealed the ordinance of secession instead of declaring it null and void. The reconstructed legislatures pensioned Confederate soldiers and their families. "Notorious and unpardoned rebels" were elected as state officers and to Congress.

Worse than this, nearly all the southern States passed laws which went far toward reducing the blacks again to slavery. In Virginia, if a negro broke his labor-contract, the employer could pursue him and compel him to work an extra month, with chain and ball if necessary. In Mississippi negro children who were orphans, or whose parents did not support them, were to be apprenticed till they became of age. Their masters could inflict upon them "moderate corporal punishment," and re-capture such as ran away. In South Carolina any negro engaging in business had to pay one hundred dollars yearly as a license. Mechanics were fined ten dollars each a year for prosecuting their trades. No negro could settle in the State without giving bonds for his good behavior and support. In Louisiana a farm laborer was required to make a year's contract; if he failed to work out the time, he could be punished by forced labor upon public works. Not all the new southern legislation was of this savage character, and this itself must be viewed in the light of the fact that the negroes, trained in irresponsibility, were inclined to idleness and theft. But it was nevertheless unjust. In some sections only the interposition of the military and of the Freedman's Bureau made life tolerable to the blacks.

As an offset to the above dangerous acts and tendencies, Congress, in the spring of 1866, passed the Fourteenth Amendment [footnote: Declared in force July 28, 1868, having been ratified by three-fourths of the States] and submitted it to the States for ratification. It was meant to insure to negroes in every State all the rights of citizens and the equal protection of the laws. If and so long as negroes were in any State forbidden to vote, it reduced that State's representation in Congress proportionally; it excluded from national and state offices certain specified Confederate leaders; and it guarded the national debt, repudiating all indebtedness on behalf of the Rebellion. Every secession State but Tennessee rejected the amendment.

Congress replied by the "iron law" of March 2, 1867. "Secessia" was divided into five districts and placed under military rule, there to remain until certain conditions were fulfilled. These conditions were, in brief, the calling of a state convention by the loyal citizens, blacks included; the framing by the convention of a constitution enfranchising negroes; the ratification of this constitution by the people and its approval by Congress; the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment by the new legislature. Having conformed to these prescriptions the State might be represented in Congress and consider itself fully restored to the Union. A supplementary law of March 19th hastened the process by giving the district commanders surveillance of registration and the initiative in calling conventions.

By June, 1868, a sufficient number of the southern States had complied with the conditions to make the Fourteenth Amendment law. Virginia, Mississippi, and Texas held out till 1870, and hence were forced to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment also. Not till January 30, 1871, were all the States again represented in both Houses of Congress as in 1860.

Edwin M. Stanton.

All through the days of congressional reconstruction the antagonism between President and Congress steadily increased. Every step in the progress encountered the President's uttermost opposition and spite. He vetoed all important reconstruction measures, which were promptly carried over his veto.

There was much violent language and bitter feeling on both sides. The irritation finally culminated when the House entered articles of impeachment against Johnson--the only case of the kind in our history involving a President. The charges were tried before the Senate in March, 1868, the Chief Justice presiding, and occupied three weeks. William M. Evarts was Johnson's counsel, and a glittering array of legal talent appeared on both sides. The main charge was that the President had wilfully violated the Tenure of Office Act in removing Secretary Stanton from the Cabinet after the Senate had once refused to concur in his removal. The House was hasty in bringing the prosecution. The President was acquitted by a vote of 19 against and 35 for impeachment--one vote less than the two-thirds necessary to impeach. The Johnson-Congressional conflict proved one of the most mortifying episodes in our country's history.

Ulysses S. Grant.