1860-1868 Chapter X FOREIGN RELATIONS FINANCE EMANCIPATIO

CHAPTER X.

FOREIGN RELATIONS--FINANCES--EMANCIPATION

A civil war of vast proportions in the world's greatest republic naturally aroused deep interest among the monarchies of Europe. Russia evinced warm friendliness to the United States. The rest of the world, save England and France, showed us no ill-will.

England, with unfriendly haste, admitted the belligerent rights of the Confederacy before Mr. Adams, our minister, could reach the British court. The North was surprised and shocked that liberty-loving, conservative England should so far side with "rebellious slave-holders." It would seem that, besides sympathy with the aristocratic structure of southern society, national envy helped to put England into this false position.

Commercial interests had greater weight. Four millions of people in England depended upon cotton manufactures for support. Three-fourths of the cotton they had used came from our southern ports, which the blockade closed. Moreover, the Confederacy declared for free trade, while the North adopted a high war tariff which drove many English goods out of American markets. The London Times complained that nearly $4,000,000 worth of English cutlery alone had been made worthless by our tariff.

An incident early in the war heightened the ill-will between the two countries. On a dark night in October, 1861, Messrs. Mason and Slidell, Confederate commissioners to England and France, ran the blockade at Charleston, and soon after took passage at Havana on the English mail steamer Trent. November 8th, 250 miles out from Havana, the United States sloop of war San Jacinto, Captain Wilkes, compelled the Trent, by a shot across her bows, to heave to, and took off the commissioners.

All England was hot with resentment. Troops were shipped to Canada, and other war preparations begun. A special messenger was hurried to Washington, demanding an apology and the release of the prisoners. Wilkes's action, though without authority in international law, was warmly approved by the people. The House of Representatives tendered him a vote of thanks. But the Government disavowed the seizure and gave up the commissioners. Mr. Seward, Secretary of State, in a dignified reply to England, insisted that the seizure was fully justified by England's own practice of searching neutral vessels on the high seas; but that, as the United States had always condemned this practice, the prisoners would be released, especially as Captain Wilkes should have brought the Trent before a prize court instead of deciding the validity of the prize himself. The action of the Government, though unpopular at the time, was undoubtedly as prudent as it was just. We could not afford to provoke war with England.

The Landing of the Allied Troops at Vera Cruz.

Our real grievance against Great Britain was that the Queen's proclamation of neutrality was not obeyed. Confederate cruisers were built in English yards, whence they publicly and boastfully sailed to prey upon our then vast merchant marine. Crews as well as ships were English. The British ministry were perfectly aware of their destination, but used all manner of artifices to avoid interfering.

Our most vicious enemy abroad was Napoleon III., so profuse yet so hypocritical in his professions of good-will. He, too, hastened to accord belligerent rights to the Confederacy. Had England not been too wary to join him, the two nations would certainly have recognized the South's independence. Napoleon was on the point of doing this alone. Seven war-vessels were, with his sanction, built for the Confederates at Bordeaux and Nantes, though he was too wily to allow them to sail when he became aware that their destination was fully known to our minister.

Far-reaching political schemes were at the bottom of Napoleon's wish for a dismembered Union. He was plotting to restore European influence in America by setting up an empire on the ruins of the Mexican republic, and he knew that the United States would never allow this while her power was unbroken. In the latter part of 1861 a French army invaded Mexico. The feeble government was overthrown after a year or two of fighting. In 1863 an empire was established, and Napoleon offered the throne to the Austrian archduke Maximilian. Meanwhile, the protests of the United States were disregarded. But when our hands were freed by the collapse of the Confederacy, Napoleon changed his tone. The French troops were withdrawn early in 1867, and Maximilian was left to his fate. The unhappy prince, betrayed by his own general, fell into the hands of the old Mexican Government, now in the ascendant, and was tried by court-martial and shot. It should be remembered, however, that France's unfriendly attitude all through the Rebellion was maintained by her unscrupulous emperor and did not reflect the wish of the French people.

The expenses of the war were colossal. From beginning to close they averaged $2,000,000 a day, sometimes running up to $3,500,000. The expenditure for the fiscal year ending July 1, 1865, was nearly $2,000,000,000. Of this the War Department required, in round numbers, $1,000, 000,000; the navy department, $123,000,000. These figures reveal the vast scale upon which the war was waged by land and sea. The national debt rose with frightful rapidity. It was $64,000,000 in 1860, $1,100,000,000 in 1863, $2,800,000,000 (the highest point reached) in 1865. State and local war debts would swell the amount to more than $4,000,000,000.

The position of Secretary of the Treasury during the war was anything but a bed of roses. The ordinary national income was hardly a drop in the bucket compared with the enormous and constantly increasing expenses. The total receipts for the year ending July 1, 1860, were only $81,000,000. How should the vast sums needed to carryon the war be raised? Resort was had to two sources of revenue--taxation and loans.

A considerable revenue was already derived from customs imposed upon imported goods. In 1861, and again in 1863, tariffs were raised enormously, professedly to increase the revenue. These high rates in a measure defeated their own purpose, altogether stopping the importation of not a few articles.

The war compelled the Government to resort to internal taxation--always unpopular and now unknown in the United States for nearly half a century. Taxes were laid upon almost everything--upon trades, incomes, legacies, manufactures. The words of Sydney Smith will apply to our internal taxes during the war:

"Taxes on the ermine which decorates the judge, and the rope which hangs the criminal; on the poor man's salt and the rich man's spice; on the brass nails of the coffin and the ribands of the bride." The tax on many finished products ranged from eight to fifteen per cent.; on some it rose to twenty per cent.

Maximilian Watching the Departure of the

Last French Troops from the City of Mexico.

But these taxes, severe as they were, could furnish only a small part of the necessary income. The Government must borrow. In the first year of the war the banks loaned the United States $150,000,000 at 7.3 per cent. interest. Many other loans were secured as the war went on--one for $500,000,000, another for $900,000,000. As security the Government issued bonds, bearing various rates of interest and payable after a certain number of years. Treasury notes were also issued and made legal tender for all debts public and private. As the Government paid its own debts with them, they were in the nature of a forced loan. Of those which bore no interest (commonly known as greenbacks) $433,000,000 were issued from first to last. Also, when property was seized for the use of the army, the owners were given certificates of indebtedness which entitled the holders to payment at the United States Treasury.

The proportion of revenue derived from each of the above sources is illustrated by the report of the treasurer of the United States for the year ending July 1, 1865. Customs yielded $85,000,000, internal revenue $209,000,000, loans $1,470,000,000.

Finance legislation during the war was more patriotic than wise, due partly to necessary haste, largely to ignorance. The internal taxes bore very unequally upon different classes. The tariff was ill-adjusted to the internal taxes, letting in at low rates some classes of goods whose home production was heavily taxed, thus discriminating in favor of the foreigner. Millions of debt and half the other economic evil of the war might have been saved by doing more to keep the paper dollar on a par with gold. Thus the banks should not have been compelled to pay in gold the loan of 1861. It forced them to suspend specie payment altogether, December 31st of that year--those of New York City first, followed by others everywhere, and by the United States itself. Gold had been at a nominal premium all through 1861, but the first recorded sale at an advance was on January 13, 1862.

172 CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION

It would have been better, also, to resort earlier to heavy loans, even at high rates, instead of flooding the country with greenbacks. The national banks, which were created on purpose to help the sale of government bonds, should have been forced to purchase new bonds instead of supplying themselves with bonds already issued, their purchase of which did the Government no good whatever. Neglect in these regards caused the paper dollar to fall in value. In July, 1864, it was worth only thirty-five cents in gold.

The finances of the Confederacy went steadily from bad to worse. The blockade cut off its revenue from import duties. Its poor credit forbade large loans. The government had to rely mainly upon paper money. This soon became almost worthless. In December, 1861, it took $120 in paper money to buy $100 in gold; in 1863 it took $1,900; in 1864, $5,000. Nearly $1,000,000,000 in paper money was issued in all. The Confederate debt at the close of the war was $2,000,000,000. Under the combined influence of depreciated currency and scarcity of goods, prices became ludicrously high.

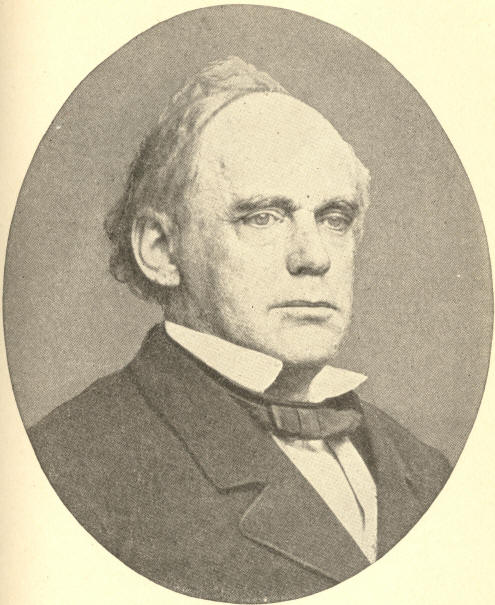

Salmon Portland Chase,

Secretary of the Treasury during the Civil War.

As early as 1862 flour was $40 a barrel and salt $1 a pound. Before the war was over, a pound of sugar brought $75, a spool of thread $20. Toward the end of the war a Confederate soldier, just paid off, went into a store to buy a pair of boots. The price was $200. He handed the store-keeper a $500 bill. "I can't change this," "Oh, never mind," replied the paper millionaire. "I never let a little matter like $300 interfere with a trade." Of course when the Confederacy collapsed all this paper money became absolutely worthless.

Mr. Lincoln and the Republican Party resorted to arms not intending the slightest alteration in the constitutional status of slavery. But the presence of Union armies on slave soil led to new and puzzling questions. What should be done with slaves escaping to the Union lines? Generals Buell and Hooker authorized slave-holders to search their camps for runaway slaves. Halleck gave orders to drive them out of his lines.

Butler, alleging that since slaves helped "the rebels" by constructing fortifications they were contraband of war, refused to return those fleeing into his camp. Congress moved up to this position in August, 1861, declaring that slaves used for hostile purposes should be confiscated. But when Fremont and Hunter issued orders freeing slaves in their military districts, President Lincoln felt obliged to countermand them, fearing the effect upon slave States that were still loyal.

As the war went on the conviction grew that peace would never be safe or permanent if slavery remained, and that the suppression of the Rebellion was postponed, jeopardized, and made costlier by every hour of slavery's life. Slaves raised crops, did camp work, and built fortifications, releasing so many more whites for service in hostile ranks, instead of doing all this, and fighting, even, for the Union.

It is interesting to trace the growth of emancipation sentiment during 1862 as it is reflected in congressional legislation.

In March army officers were forbidden to return fugitive slaves. In April slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia, with compensation to owners. At the same time Congress adopted a pet scheme of Mr. Lincoln's, offering compensation to any State that would free its slaves. None accepted. There were about 3,000 slaves in the District. Upon the day of their emancipation they assembled in churches and gave thanks to God. In June slavery in the Territories--that bone of contention through so many years--was forever prohibited. In July an act was passed freeing rebels' slaves coming under the Government's protection, and authorizing the use of negro soldiers.

Already President Lincoln was meditating universal emancipation. September 22d the friends of liberty were made glad by a preliminary proclamation, announcing the President's intention to free the slaves on January 1, 1863, should rebellion then continue to exist. It is said that Mr. Lincoln would have given this notice earlier but for the gloomy state of military affairs.

The day comes. The proclamation goes forth that all persons held as slaves in the rebellious sections "are and henceforth shall be free." The blot which had so long stained our national banner was wiped away. The Constitution of course does not expressly authorize such an act by the President, but Mr. Lincoln defended it as a "necessary war measure," "warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity."

This bold, epoch-making deed, the death-warrant of slavery here and throughout the world, evoked serious hostility even at the North. The elections in the fall of 1862 and the spring of 1863 showed serious losses for the administration party. Emancipation, too, doubtless added rancor and verve for a time to southern belligerency. But the fresh union, spirit, and strength it soon brought to the northern cause were tenfold compensation. Besides, it vastly exalted our struggle in the moral estimate of Christendom, and lessened danger of foreign intervention.

The War President trod at no time a path of flowers. Strong and general as was Union sentiment at the North, extremely diverse feelings and views prevailed touching the methods and spirit which should govern the conduct of the war. Certain timid, discouraged, or disappointed Republicans, seeing the appalling loss of blood and treasure as the war went on, and the Confederacy's unexpected tenacity of life, demanded peace on the easiest terms inclusive of intact Union. Secretaries Seward and Chase were for a time in this temper. The doctrinaire abolitionists bitterly assailed President and Congress for not making, from the outset, the extirpation of slavery the main aim of hostilities. Even the great emancipation pacified them but little.

The Democrats proper entered a far more sensible, in fact a not wholly groundless, complaint exactly the contrary. They charged that the Administration, in hopes to exhibit the Democracy as a peace party (which from 1862 it more and more became), was making the overthrow of slavery its main aim, waging war for the negro instead of for the Union. They complained also that not only in anti-slavery measures but in other things as well, notably in suspending habeas corpus, the Administration was grievously infringing the Constitution.

Yet a fourth class, a democratic rump of southern sympathizers, popularly called "copperheads," wishing peace at any price, did their best to encourage the Rebellion .. They denounced the war as cruel, needless, and a failure. They opposed the draft for troops, and were partly responsible for the draft riots in 1863. Many of them were in league with southern leaders, and held membership in treasonable associations. Some were privy to, if not participants in, devilish plots to spread fire and pestilence in northern camps and cities, Partly through influence of the more moderate, several efforts to negotiate peace were made, fortunately every one in vain.

But despite the attacks of enemies and the importunities of weak or short-sighted friends, President Lincoln steadily held on his course. The masses of the people rallied to his support, and in the presidential election of 1864 he was re-elected by an overwhelming majority, receiving 212 electoral votes against 21 for General McClellan, the democratic candidate.