1860-1868 Chapter IX THE WAR ON THE SEA

CHAPTER IX.

THE WAR ON THE SEA

Naval operations during the war fall into three great classes: Those upon inland waters, the Mississippi especially; those along the coast; and those upon the high seas. The first class has already been touched upon in connection with the Mississippi campaigns. The naval work along the coast and upon the high seas is the subject of the present chapter. Only the more important features can be sketched. At the outbreak of the Rebellion our navy was totally unprepared for war. Forty-two vessels were in commission, but most of them were in distant seas or in southern ports. The service was weak with secession sentiment. Between March and July, 1861, 259 naval officers resigned or were dismissed.

Gideon Welles.

Secretary Welles went energetically to work. Vessels in foreign waters were called home, the keels of new craft laid in northern dockyards, and stout merchant ships bought and fitted up for the rough usage of war. By the end of 1861 the navy numbered 264 vessels. At the close of the war it had 671 ships, carrying 4,610 guns and 50,000 sailors.

The first work--a gigantic one--was to blockade the southern ports. This involved the constant patrolling of more than 3,000 miles of dangerous coast, indented with innumerable inlets, sounds, and bays. But within a year a fairly effective blockade was in force from Virginia to Texas, drawn tighter and tighter as the navy increased in size. The effectiveness of the blockade is sufficiently proved by the dearth at the South. The South had cotton enough to sell--$300,000,000 worth in gold at the end of the war--and Europe was greedy to buy; but she could not get her wares to market. Fifteen hundred prizes, worth $30,000,000, were taken during the war.

The details of the blockade must be left to the reader's imagination. Important as the work was, it was comparatively monotonous and dull--ceaseless watching day and night in all weather, week after week and month after month. Now and then the routine would be broken by the excitement of a chase. A suspicious-looking sail would be spied in the offing and pursued, perhaps, far out to sea.

Again, the low hull of a blockade-runner would be seen creeping around a point and heading for the open sea. Or on a still night the throb of engines and the splash of paddle-wheels would give warning that some guilty vessel was trying to steal into port under cover of darkness. Then came the flare of rockets to notify the rest of the blockading fleet, the hot pursuit with boilers crowded to bursting, the boom of the big guns fired at random in the dark, and the exultation of a capture or the disappointment of failure.

Blockade-running became a regular business, enormously profitable. Moonless and cloudy nights were of course the most favorable times for eluding the blockade; but the swift steamers, sitting low in the water and painted a light neutral tint, could not easily be detected by day at a little distance, especially as they burned smokeless coal. The bolder skippers would take all chances. Under cover of a fog they would steal into or out of harbor at risk of going aground, or set sail boldly on a bright moonlight night, when the blockaders would naturally relax their vigilance a little.

Occasionally some dare-devil would crowd on all steam and dash openly through the sentinel fleet, trusting to speed to escape being hit or captured. When hard pressed, the blockade-runner would beach his craft, set it afire, and take to the woods. At the close of the war thirty wrecks of blockade-runners were rotting on the sands near Charleston Harbor.

In connection with the blockade a number of naval expeditions were sent against various points along the coast. In October, 1861, a fleet under Flag-Officer Dupont, consisting of a steam frigate, a dozen or more gunboats, with numerous transports and coaling-schooners, and carrying 12,000 troops under General T. W. Sherman, set sail from Hampton Roads for Port Royal, S. C. After a stormy passage the fleet anchored off the harbor on November 4th. On opposite sides of the entrance, two and a half miles apart, stood Forts Walker and Beauregard--strong earthworks, mounting one 23 the other 20 guns, and garrisoned by 1,700 men.

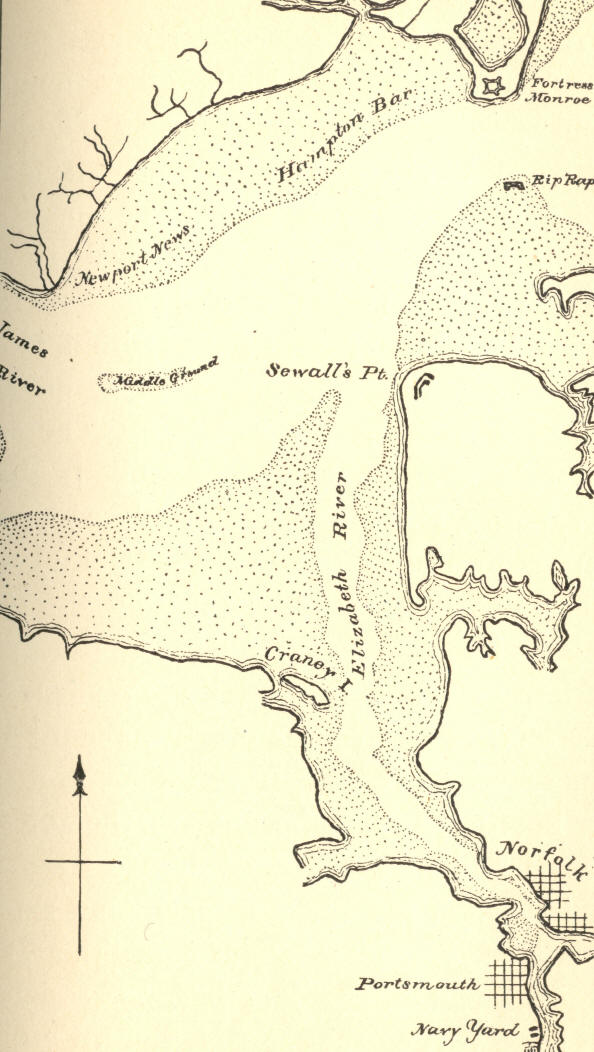

Map of Hampton Roads

The 7th dawned bright and clear, the sea smooth as glass. About nine o'clock the bombardment began. The fleet steamed slowly round and round in an ellipse between the forts, each vessel as it came within range pouring in its fire, then passing on and waiting its turn to fire again. The cannonade was concentrated upon Fort Walker. The moving ships offered a poor mark to the fort, while the aim of the fleet was very accurate, covering the gunners with sand and dismounting the guns. After four hours' action Fort Walker was evacuated, and soon Fort Beauregard also in consequence.

Port Royal was the finest harbor on the coast, and was of great value to the navy all through the war as a repair and supply station. Dupont sent out expeditions, and by the end of the year had possession of a large part of the coast of South Carolina and Georgia. In the following spring expeditions from Port Royal regained Fernandina and St. Augustine on the Florida coast. In April Fort Pulaski, a strong brick work at the mouth of the Savannah River, was reduced by eleven batteries planted on a neighboring island, its surrender completing the blockade of Savannah.

Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds, on the coast of North Carolina, swarmed with blockade-runners. Rivers, canals, and railroads formed a network of communications with the interior, and vessels were constantly slipping to sea with cargoes of cotton, to return with munitions of war. Hatteras Inlet, seized in August, 1861, was not a sufficient basis for the blockade. In February, 1862, a fleet bearing 11,500 soldiers, under General Burnside, arrived at Roanoke Island, which lies between the two great sounds. The troops were landed, and on the 8th, charging over marshy ground, sometimes waist-deep in water, carried the batteries and gained possession of the island. Newbern, one of the most important ports of North Carolina, was captured a month later, and Fort Macon, commanding the entrance to Beaufort Harbor, surrendered in April.

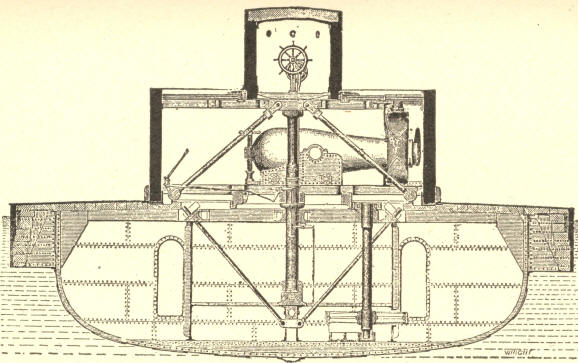

Meanwhile what had the Confederates been doing in naval matters? When the Norfolk navy-yard was abandoned in April, 1861, the fine old frigate Merrimac was scuttled. She was raised by the Davis Government and converted into an ironclad ram--a novelty in those days. The hull was cut down to the water's edge, and a stout roof, 170 feet long, with sloping sides and a flat top, built amidships and plated with four inches of iron. This roof was pierced for ten guns--four rifles and six nine-inch smooth-bores.

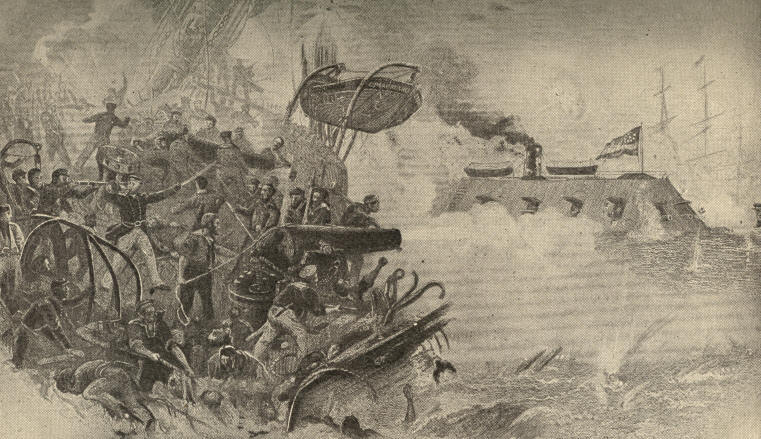

On March 8, 1862, the Union fleet, consisting of the Cumberland, Congress, Minnesota, and some smaller craft, rode lazily at anchor in Hampton Roads. About noon a curious looking structure was seen coming down Elizabeth River. It was the Merrimac. She steered straight for the Cumberland. The latter poured in a broadside from her heavy ten-inch guns, but the balls glanced off the ram's sloping iron sides like peas. The Merrimac's iron beak crashed into the Cumberland's side, making a great hole. In a few minutes the old warsloop, working her guns to the water's edge, went down in fifty-four feet of water, 120 sick and wounded sinking with her.

The Sinking of the Frigate Cumberland by the Merrimac in Hampton Roads, March 8, 1862

The Congress had meanwhile been run aground. The Merrimac fired hot shot, setting her afire. Nearly half the crew being killed or wounded, she surrendered, her magazine exploding and blowing her up at midnight. The Minnesota, hastening up with two other vessels from Fortress Monroe to aid her sisters, had run aground. Being of heavy draught, the Merrimac could not get near enough to do her much damage, and at nightfall steamed back to her landing. As the telegraph that night flashed over the land the news of the Merrimac's victory, dismay filled the North, exultation the South. What was to stay the career of the invulnerable monster? Could it not destroy the whole United States navy of wooden ships?

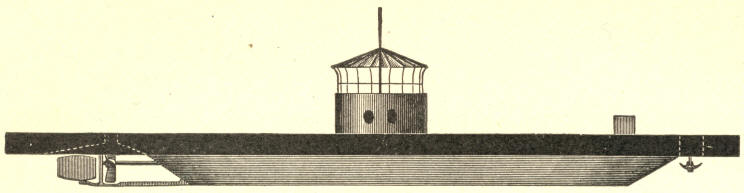

Next morning the Merrimac reappeared to complete her work of destruction. As she drew near the stranded Minnesota, a strange little craft moved out from the side of the big frigate and headed straight for the iron-clad. It was Ericsson's Monitor, which had arrived from New York at midnight. The Confederate characterization of it as a "cheese-box on a raft" is still the best description of its appearance. Its lower hull, 122 feet long and 34 wide, was protected by a raft-like overhanging upper hull, 172 feet long and 41 wide. Midway upon her low deck, which rose only a foot above the water, stood a revolving turret 21 feet in diameter and nine in height. It was made of iron eight inches thick, and bore two eleven-inch guns throwing each a 180-pound ball. Near the bow rose the pilot-house, made of iron logs nine inches by twelve in thickness. The side armor of the hull was five inches thick, and the deck was covered with heavy iron plates.

John Ericsson.

For three hours the iron-clads fought. The Merrimac's shot glanced harmlessly off the round turret, while her attempts to run the Monitor down failed. Meanwhile the big guns in the Monitor's turret, firing every seven minutes, were pounding the ram's sides with terrible blows. The Merrimac's armor was at points crushed in several inches, but nowhere pierced, About noon the fight stopped, as if by mutual consent. It was a drawn battle, but the career of the Merrimac had ended. Upon McClellan's advance, in May, she was blown up. The Monitor received no serious injury in this action, but the next December she foundered in a storm off Cape Hatteras.

The invention of the Monitor revolutionized naval warfare, and set European nations to building the ponderous iron-clad navies of the present day. The United States Government soon contracted for twenty single-turret monitors, and four double-turreted ones with fifteen-inch guns.

The Confederates now went to building iron-clads on the model of the Merrimac. On the morning of January 31, 1863, the iron-clads Palmetto State and Chicora steamed out of Charleston Harbor, in a dense fog, and attacked the blockading fleet of wooden vessels. After ramming one ship and sending a shot through the boiler of another, they put back to port.

In April, Admiral Dupont tried to seize Charleston Harbor with his fleet of seven monitors and two iron-clads. In a two hours' action the monitors were seriously injured by the heavy guns of the forts, and the fleet withdrew. In August, land batteries reduced Fort Sumter almost to ruins, and in the following month Fort Wagner was abandoned. June 17th, the iron-clad Atlanta, armed with a torpedo at the end of a spar, ran down from Savannah to engage with two monitors guarding the mouth of the river. She got aground, rendering the torpedo useless. The fifteen-inch guns of the monitors pierced her armor, and in a few minutes she surrendered.

The Albemarle proved a more dangerous foe. The last of April, 1864, it descended Roanoke River, smashed the gunboats at the mouth, and compelled the surrender of the forts and the town of Plymouth. A few days later it attacked a fleet of gunboats below the mouth of the river. After a severe tussle, inflicting and receiving considerable damage, it steamed back to Plymouth.

Here it lay at the wharf till October, when it was sunk by Lieutenant Cushing, already famous for daring exploits under the very noses of the enemy. On the night of October 27th, young Cushing approached the ironclad in a steam launch with a torpedo at the end of a spar projecting from the bow.

The Original Monitor

Jumping his boat over the log boom surrounding the ram, in the thick of musketry fire from deck and shore, Cushing calmly worked the strings by which the intricate torpedo was fired. It exploded under the vessel's overhang, and she soon sunk.

At the moment of the explosion a cannonball crashed through the launch. Cushing plunged into the river and swam to shore through a shower of bullets. After crawling through the swamps next day, be found a skiff and paddled off to the fleet. Of the launch's crew of fourteen, only one other escaped.

The stronghold of the Confederacy on the Gulf was Mobile. Two strong forts, mounting twenty-seven and forty-seven guns, guarded the channel below the city, which was further defended by spiles and torpedoes. In the harbor, August 5, 1864, lay the iron-clad ram, Tennessee, and three gunboats, commanded by Admiral Buchanan, formerly captain of the Merrimac. Farragut determined to force a passage. Before six o'clock in the morning his fleet of four monitors and fourteen wooden ships, the latter lashed together two and two, got under way, Farragut taking his station in the main rigging of the Hartford. The action opened about seven.

One of the monitors struck a torpedo and sunk. The Brooklyn, which was leading, turned back to go around what seemed to be a nest of torpedoes. The whole line was in danger of being huddled together under the fire of the forts. Farragut boldly took the lead, and the fleet followed. The torpedo cases could be heard rapping against the ships' bottoms, but none exploded.

The forts being safely passed, the Confederate gunboats advanced to the attack. One of these was captured, the other two escaped. The powerful iron-clad Tennessee now moved down upon the Union fleet. It was 209 feet long, with armor from five to six inches thick. Farragut ordered his wooden vessels to run her down. Three succeeded in ramming her squarely. She reeled under the tremendous blows, and her gunners could not keep their feet. A monitor sent a fifteen-inch ball through her stern. Her smoke-stack and steering-chains were shot away, and several port shutters jammed. About ten A.M., after an action of an hour and a quarter, the ram hoisted the white flag. The forts surrendered in a few days.

January 15, 1865, Fort Fisher, a strong work near Wilmington, N. C, mounting seventy-five guns, was captured by a joint land and naval expedition under General Terry and Admiral Porter. This was the last great engagement along the coast.

The story of the war upon the high seas is quickly told. Swift and powerful cruisers were built in English ship-yards, with the connivance of the British Government, whence they sailed to prey upon our commerce. The Florida, Georgia, Shenandoah, Chameleon, and Tallahassee, were some of the most famous in the list of Confederate cruisers. During 1861, fifty-eight prizes were taken by them. American merchant vessels were driven from the sea. The Shenandoah alone destroyed over $6,000,000 worth in vessels and cargoes.

The two most celebrated of these sea-rovers were the Sumter and the Alabama, both commanded by Captain Semmes, formerly of the United States Navy. The Sumter was a screw steamer of 600 tons, a good sailer and sea-boat. She was bought by the Confederate Government and armed with a few heavy guns. On June 30, 1861, she ran the blockade at Charleston, and began scouring the seas. All through the fall she prowled about the Atlantic, taking seventeen prizes, most of which were burned. Many United States cruisers were sent after her, but she eluded or escaped them all. Early in 1862 the Sumter entered the port of Gibraltar. Here she was blockaded by two Union gunboats, and Semmes finally sold her to take command of the Alabama.

The Alabama was built expressly for the Confederacy at Laird's ship-yard, Liverpool, and although her character was perfectly well known, the British Government permitted her to go to sea. She was taken to one of the Azores Islands, where she received her armament and her captain. The officers were Confederates, the crew British.

She began her destructive career in August, 1862. By the last of October she had taken twenty-seven prizes. In January she sunk the gunboat Hatteras, one of the blockading fleet off Galveston, Tex. After cruising in all seas, the Alabama, in 1864, returned to the European coast, having captured sixty-five vessels and destroyed property worth between $6,000,000 and $7,000,000.

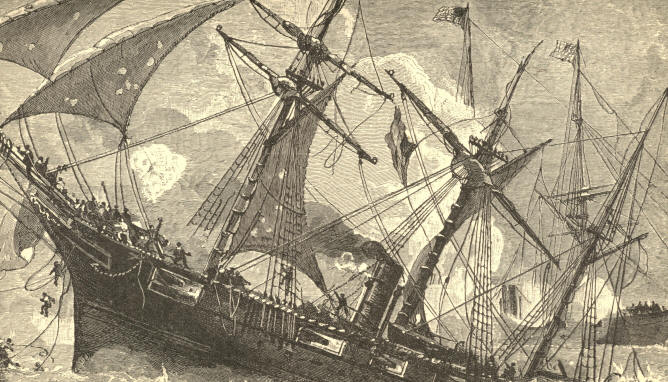

On June 11th, Semmes put into the harbor of Cherbourg, on the coast of France. Captain Winslow, commanding the United States steamer Kearsarge, cruising in the neighborhood, heard of the famous rover's arrival, and took his station outside the harbor. About ten o'clock on the morning of June 19, 1864, the Alabama was seen coming out of port, attended by a French man-of-war and an English steam yacht. Captain Winslow immediately cleared the decks for action. It was a clear, bright day, with a smooth sea. The fight took place about seven miles from shore. The two ships were pretty equally matched, each being of about 1,000 tons burden. The Kearsarge had the heavier smooth-bore guns, but the Alabama carried a 100-pound Blakely rifle. The Kearsarge was protected amidships by chain cables.

The Alabama opened the engagement. The Kearsarge replied with a cool and accurate fire. The action soon grew spirited. Solid shot ricochetted over the smooth water. Shells crashed against the sides or exploded on deck. The two ships sailed round and round a common centre, keeping about half a mile apart. In less than an hour the Alabama was terribly shattered and began to sink. She tried to escape, but water put out her engine fires. Semmes hoisted the white flag. In a few minutes the Alabama went down, her bow rising high in the air. Boats from the Kearsarge rescued some of the crew. The English yacht picked up others, Semmes among them, thus running off with Winslow's prisoners. The Kearsarge had received little damage.

The Sinking of the Alabama

The sinking of the Alabama ended the career of the Confederate cruisers. American commerce had been nearly driven from the ocean, and, moreover, the days of peace on land and sea alike were near at hand.