1860-1868 Chapter VIII COLLAPSE OF THE CONFEDERACY

CHAPTER VIII.

COLLAPSE OF THE CONFEDERACY

Gettysburg was the last general engagement in the East during 1863. The next spring, as we have noticed, Grant was appointed Lieutenant-General, with command of all the northern armies, now numbering over 600,000 effectives. This vast body of men he proposed to use against the fast-weakening Confederacy in concerted movements. Sherman's part in the great plan has already been traced. The hardest task, that of facing Lee, the hero of Vicksburg and Chattanooga [he] reserved for himself. Greek thus met Greek, and the death-grapple began.

May 4th the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan and entered the Wilderness, Meade in immediate command, with 120,000 men present for duty. Lee, heading an army of 62,000 veterans, engaged his new antagonist without delay. For two days the battle raged in the gloomy woods. There was no opportunity for brilliant manoeuvres. The men of the two armies lay doggedly behind the trees, each blazing away through the underbrush at an unseen foe, often but a few yards off, while a stream of mangled forms borne on stretchers came steadily pouring to the rear. The tide of battle surged this way and that, with no decisive advantage for either side.

But Grant, as Lee said of him, "was not a retreating man." If he had not beaten, neither had he been beaten. Advance was the word. On the night of the 7th he began that series of "movements by the left flank" which was to force Lee forever from the Rappahannock front. The army stretched nearly north and south, facing west. Warren's corps, at the extreme right, quietly withdrew from the enemy's front, and marching south took a position beyond Hancock's, hitherto the left. Sedgwick's corps followed.

Death of General Sedgwick at Spottsylvania. May 9, 1864.

By this sidling movement the army worked its way south, all the while presenting an unbroken front to the enemy. Yet, on reaching Spottsylvania, Grant found Lee's army there before him. Sharp fighting began again on the 9th and continued three days, but was indecisive, mainly from the wild nature of the country, heavily timbered, with only occasional clearings.

An early morning attack on the 12th carried a salient angle in the centre of the Confederate line, securing 4,000 prisoners and twenty guns. All that day and far into the night Lee desperately strove to dislodge the assailants from this "bloody angle." Five furious charges were stubbornly repulsed, the belligerents between these grimly facing each other from lines of rifle-pits often but a few feet apart. Bullets flew thick as hail, a tree eighteen inches through being cut clean off by them. Great heaps of dead and wounded lay between the lines, and "at times a lifted arm or a quivering limb told of an agony not quenched by the Lethe of death around." Lee did not give up this death-grapple till three o'clock in the morning, when he fell back to a new position. His losses here in killed and wounded were about 5,000; Grant's about 6,000.

Rains now compelled both armies to remain quiet for several days. Meantime news reached Grant that Butler, who was to have moved up the James with his army of 20,000 and co-operate with the main army against Richmond, had suffered himself to be "bottled up" at Bermuda Hundred, a narrow spit of land between the James and Appomattox Rivers, the Confederates having "driven in the cork." Re-enforcements reached Grant, however, which made good all his losses.

On the 19th, after an unsuccessful assault the day before, he resumed the flanking movement, and reached and passed the North Anna. But Lee pushed in like a wedge between the two parts of the Union army, separated by crossing the river at different points, and after some fighting, Grant re-crossed and resumed his march to the south. Lee, again moving on shorter lines, reached Cold Harbor before Grant.

The outer line of Confederate intrenchments at Cold Harbor was carried on June 1st, and at early dawn on the 3d a charge made along the whole front. Under cover of a heavy artillery fire the men advanced to the enemy's rifle-pits and carried them. They then swept on toward the main line. The ground was open, and the advancing columns were exposed to a terrible storm of iron and lead. Artillery cross-fire swept through their ranks from right to left. The troops pressed close up to the works, but could not carry them. They intrenched, however, and held the position gained, at some points within thirty yards of the hostile ramparts. The Union loss was very heavy, not less than 6,000; the Confederates, fighting under shelter, lost comparatively few.

During the next ten days the men lay quietly in their trenches. Both forces had now moved so far south that Grant's hope of getting between Lee's army and Richmond had to be abandoned. He therefore decided to cross the James and take a position south of Richmond, whence he could threaten its lines of communication, while that river would furnish him a secure base of supplies.

The two hosts now began a race for Petersburg, an important railway centre, twenty- two miles south of Richmond. Grant's advance reached the town first, but delayed earnest attack, and on the morning of the 15th Lee's veterans, after an all-night's march, flung themselves into the intrenchments. Grant spent the next four days in vain efforts to dislodge them. On the 19th he gave up this method of assault, and began a regular siege. His losses in killed and wounded hereabouts had been almost 9,000.

Things now remained comparatively quiet till late in July. Both sides were busy strengthening their intrenchments. Lee held both Richmond and Petersburg in force, besides a continuous line between the two. Attempts to break this line and to cut the railroads around Petersburg led to several engagements which would have been considered great battles earlier in the war.

General David Hunter.

Grant's total losses from the crossing of the Rapidan to the end of June were 61,000, but re-enforcements promptly filled his ranks. The Confederate loss cannot be accurately determined, but was probably about two-thirds as great.

Through July one of Burnside's regiments, composed of Pennsylvanians used to such business, had been working at a mine under one of the main redoubts in front of Petersburg. A shaft 500 feet long was dug, with a cross gallery 80 feet in length at the end square under the redoubt. This chamber was charged with 8,000 pounds of powder, which was fired July 30th. The battery and brigade immediately overhead were blown into the air, and the Confederate soldiers far to left and right stunned and stupefied with terror. For half an hour the way in to Petersburg was open. Why did none enter? The answer is sad.

Grant had splendidly fulfilled his part by a feint to Deep Bottom across the James, which had drawn thither all but about one division of Lee's Petersburg force. But Meade, at a late hour on the 29th, changed the entire plan of assault, which Burnside had carefully arranged, and to lead which a fresh division had been specially drilled. Then there was lamentable inefficiency or cowardice on the part of several subordinate officers. The troops charged into the great, cellar-like crater, twenty-five feet deep, where, for lack of orders, they remained huddled together instead of pushing on. The Confederates rallied, and after shelling the crater till more of its occupants were dead than alive, charged and either routed the living or took them prisoners.

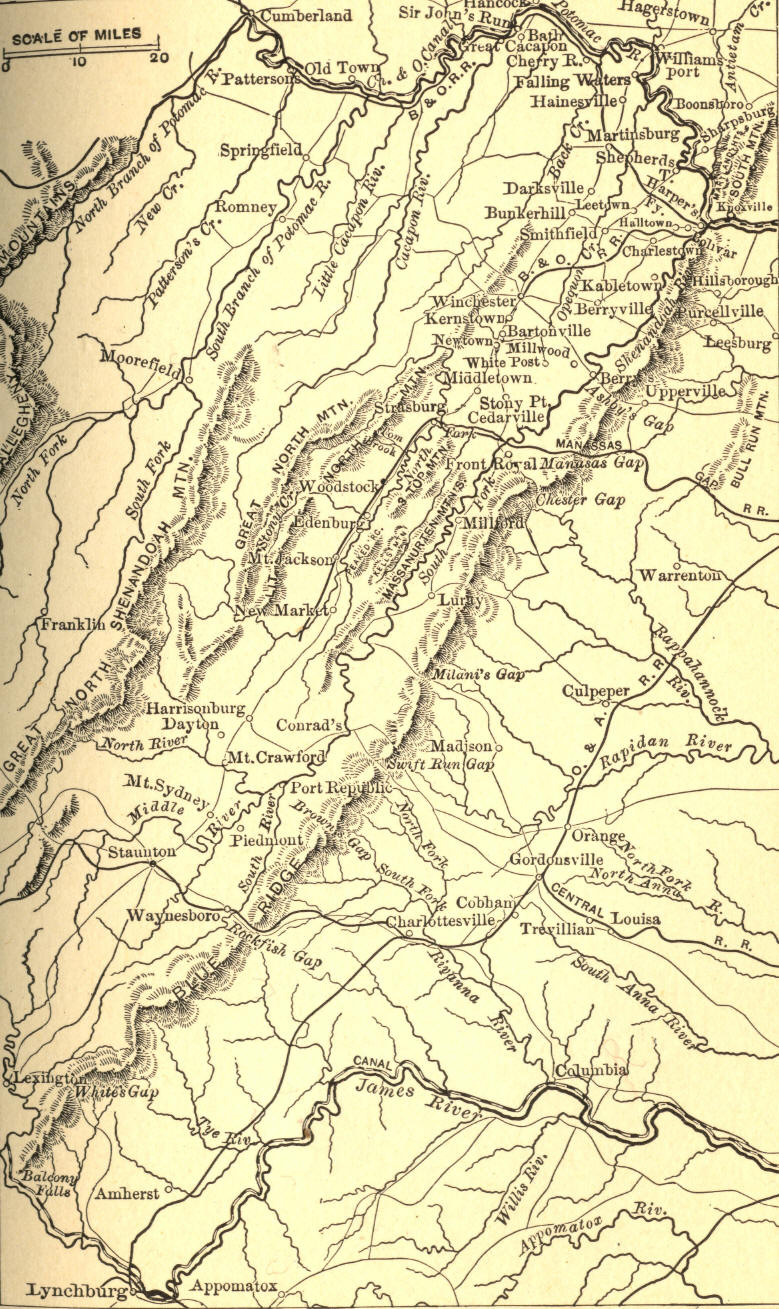

The Shenandoah Valley.

During the summer and fall of 1864 the scene of active operations was shifted to the Shenandoah Valley. The latter part of June Lee sent Early, 20,000 strong, to make a demonstration against Washington, hoping to scare Grant away from Petersburg. Early moved rapidly down the valley, hustling Hunter before him, who escaped only by making a detour to the west, thus leaving Washington open. Thither Early pushed with all speed.

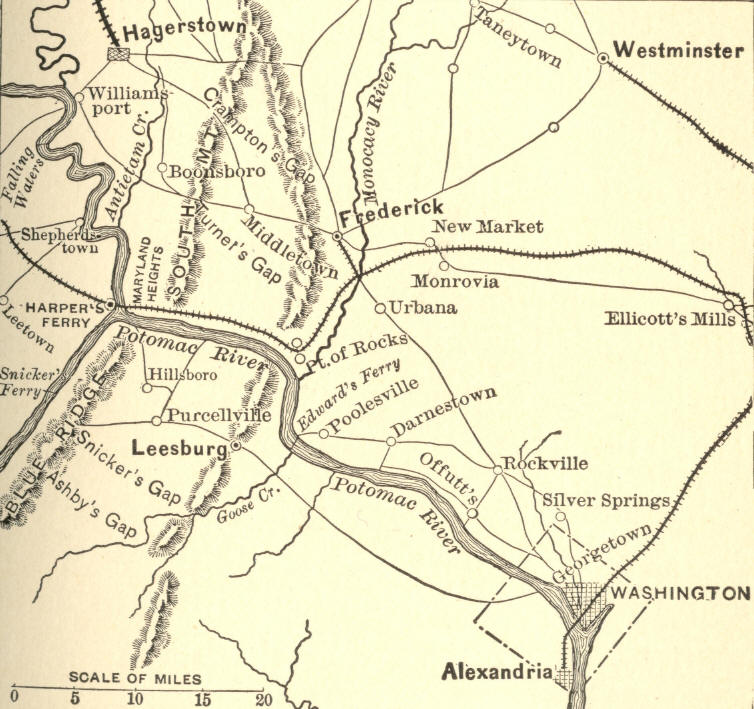

General Lew Wallace hastily gathered up the few troops at his disposal and hurried out from Baltimore to meet him. Wallace was defeated at the Monocacy River July 9th, but precious time was gained for the strengthening of Washington. When Early arrived before the city on the 11th, Grant's re-enforcements had not yet come, and the fate of the capital trembled in the balance. Early happily delayed his attack till the morrow, and that night two of Grant's veteran corps landed in Washington, President Lincoln, in his anxiety, being on the wharf to meet them. Once more Washington was safe, and Early fell back, pressed by the newcomers.

General Early's Maryland Campaign.

The pursuit was feeble, however, and the last of July Early swooped down the valley again. A detachment pushed into Pennsylvania and burned Chambersburg. All through the war the Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley had been an annoyance and a menace. Grant now determined to put a definite stop to this, and sent the dashing General Sheridan for the work with 30,000 troops, including 8,000 cavalry. Sheridan pushed Early up the Shenandoah, defeating him at Opequon Creek, September 19th, and at Fisher's Hill two days later.

One-half of Early's army had been destroyed or captured, and the rest driven southward. Sheridan then, in accordance with Grant's orders, that the enemy might no longer make it a base of operations against the capital, laid waste the valley so thoroughly that, as the saying went, not a crow could fly up or down it without carrying rations. Spite of this, Early, having been re-enforced, entered the valley once more. The Union army lay at Cedar Creek.

Sheridan had gone to Washington on business, leaving General Wright in command. On the night of October 18th, the wily Confederate crept around to the rear of the Union left, and attacked at daybreak. Wright was completely surprised, and his left wing fled precipitately, losing 1,000 prisoners and 18 guns. He ordered a retreat to Winchester. The right fell slowly back in good order, interposing a steady front between Early and the demoralized left.

Meanwhile Sheridan, who had reached Winchester on his return, snuffed battle, and hurried to the scene. Now came "Sheridan's Ride." Astride the coal-black charger immortalized by Buchanan Read's verse, he shot ahead and dashed upon the battle-field shortly before noon, his horse dripping with foam. His presence restored confidence, and the army steadily awaited the expected assault. It came, was repulsed, was reciprocated. Early was halted, then pushed, then totally routed, and his army nearly destroyed. It was one of the most signal and telling victories of the war. In a month's campaign Sheridan had killed and wounded 10,000 of the enemy and taken 13,000 prisoners.

All this time the siege of Petersburg was sturdily pressed. In August, Grant got possession of the Weldon Railroad, an important line running south from Petersburg. During the next month fortifications on the Richmond side of the James were carried and held. Through the winter Grant contented himself with gradually extending his lines around Petersburg, trying to cut Lee's communications, and preventing his sending troops against Sherman. He had a death-grip upon the Confederacy's throat, and waited with confidence for the contortions which should announce its death.

The spring of 1865 found the South reduced to the last extremity. The blockade had shut out imports, and it is doubtful if ever before so large and populous a region was so far from being self-sustaining. Even of food-products, save corn and bacon, the dearth became desperate.

Wheat bread and salt were luxuries almost from the first. Home-made shoes, with wooden soles and uppers cut from buggy tops or old pocketbooks, became the fashion. Pins were eagerly picked up in the streets. Thorns, with wax heads, served as hairpins. Scraps of old metal became precious as gold.

The plight of the army was equally distressing. Drastic drafting had long since taken into the army all the able-bodied men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five. Boys from fourteen to eighteen, and old men from forty-five to sixty, were also pressed into service as junior and senior reserves, the Confederacy thus, as General Butler wittily said, "robbing both the cradle and the grave." Lee's army had been crumbling away beneath the terrible blows dealt it by Grant. He received some re-enforcements during 1864, but in no wise enough to make good his losses. When he took the field in the spring of 1865, his total effective force was 57,000. Grant's army, including Butler's and Sheridan's troops, numbered 125,000.

Lee now perceived that his only hope lay in escaping from the clutches of Grant and making a junction with Johnston's army in North Carolina. Grant was on the watch for precisely this. On March 29th Sheridan worked around into the rear of the Confederate right. Lee descried the movement, and extended his lines that way to obviate it. A force was sent, which drove Sheridan back in some confusion. Re-enforced, he again advanced and beat the forces opposed to him rearward to Five Forks. Here, April 1st, he made a successful charge, before which the foe broke and ran, leaving 4,500 prisoners.

Fearing an attack on Sheridan in force which might let Lee out, Grant sent reenforcements, at the same time keeping up a roaring cannonade along the whole line all night. At five on the morning of the 2d, a grand assault was made against the Confederate left, which had been weakened to extend the right. The outer, intrenchments, with two forts farther in, were taken. Lee at once telegraphed to President Davis that Petersburg and Richmond must be immediately abandoned.

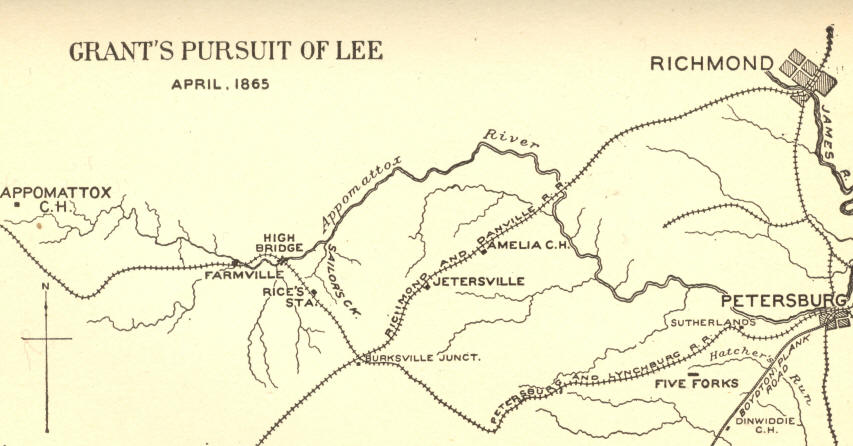

Grant's Pursuit of Lee; April, 1865

It was Sunday, and the message reached Mr. Davis in church. He hastened out with pallid lips and unsteady tread. A panic-stricken throng was soon streaming from the doomed city. Vehicles let for one hundred dollars an hour in gold. The state-prison guards fled and the criminals escaped. A drunken mob surged through the streets, smashing windows and plundering shops. General Ewell blew up the iron-clads in the river and burned bridges and storehouses. The fire spread till one-third of Richmond was in flames. The air was filled with a "hideous mingling of the discordant sounds of human voices--the crying of children, the lamentations of women, the yells of drunken men--with the roar of the tempest of flame, the explosion of magazines, the bursting of shells." Early on the morning of the 3d was heard the cry, "The Yankees are coming!" Soon a column of blue-coated troops poured into the city, headed by a regiment of colored cavalry, and the Stars and Stripes presently floated over the Confederate capital.

The Confederacy was tottering to its fall. Lee had begun his retreat on the night of the 2d, and was straining every nerve to reach a point on the railroad fifty miles to the west, whence he could move south and join Johnston. Grant was too quick for him. Sending Sheridan in advance to head him off, he himself hurried after with the main army. Gray and blue kept up the race for several days, moving on nearly parallel lines. Sheridan struck the Confederate column at Sailor's Creek on the 6th, and a heavy engagement ensued, in which the southern army lost many wagons and several thousand prisoners.

Lee's band was in a pitiable plight. Its supplies had been cut off, and many of the soldiers had nothing to eat except the young shoots of trees. They fell out of the ranks by hundreds, and deserted to their homes near by. With all hope of escape cut off, and his army dropping to pieces around him, Lee was at last forced to surrender. To this end he met Grant, on April 9th, at a residence near Appomattox Court House.

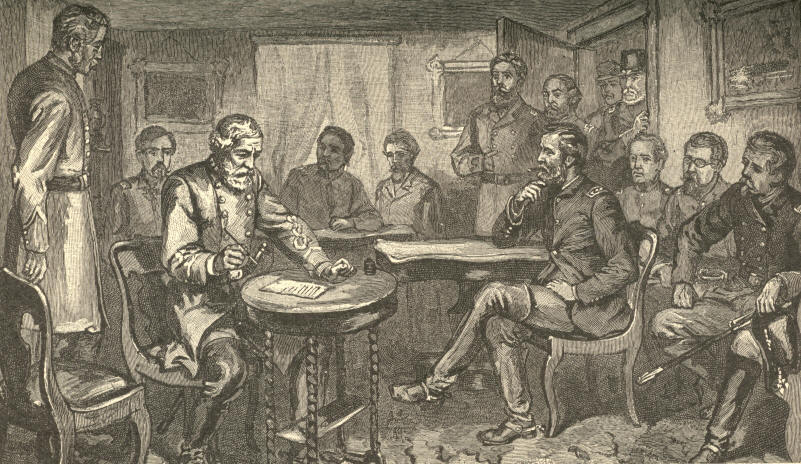

The personal appearance of the two generals at this interview presented a striking, not to say ludicrous, contrast. Lee, who was a tall, handsome man, was attired in a new uniform, showing all the insignia of his rank, with a splendid dress-sword at his side. Grant, wholly unprepared for the interview, wore a private's uniform, covered with mud and dust from hard riding that day. His shoulder-straps were the only mark of his high rank, and he had no sword. Having served together in the Mexican War, they spent some time in a friendly conversation about those old scenes. Grant then wrote out the terms of surrender, which Lee accepted. The troops were to give their paroles not to take up arms again until properly exchanged, and officers might retain their side-arms, private horses, and baggage. Anxious to heal the wounds of the South, Grant, with rare thoughtfulness, allowed privates also to take home their own horses.

General Lee Signing the Terms of Surrender at Appomattox Court-House.

"They will need them for the spring ploughing," he said. The 19,000 prisoners captured during the last ten days, together with deserters, left, in Lee's once magnificent army, but 28,356 soldiers to be paroled. The surrendering general was compelled to ask 25,000 rations for these famished troops, a request which was cheerfully granted.

While all loyal hearts were rejoicing over the news of Lee's surrender, recognized as virtually ending the war, a pall suddenly fell upon the land. On the evening of April 14th, while President Lincoln was sitting in a box at Ford's Theatre in Washington, an actor, John Wilkes Booth, crept up behind him, placed a pistol to his head, and fired. Brandishing his weapon, and crying, "Sic semper tyrannis," the assassin leaped to the stage, sustaining a severe injury. Regaining his feet, he shouted, "The South is avenged!" and made his escape.

The bullet had pierced the President's brain and rendered him insensible. He was removed to a house near by, where he died next morning. His body was taken to Springfield, Ill., for burial, and a nation mourned above his grave, as no American since Washington had ever been mourned for before. The South repudiated and deplored the foul deed. Well it might, for, had Lincoln lived, much of its sorrow during the next years would have been avoided.

Booth was only one of a band of conspirators who had intended also to take off General Grant and the whole Cabinet. By a strange good fortune Secretary Seward, sick in bed, was the only victim besides the President. He was stabbed three times with a bowie-knife, but not fatally. After a cunning flight and brave defence Booth was captured near Port Royal, and killed. Of the other conspirators some were hanged, some imprisoned.

The Confederacy collapsed. Johnston's army surrendered to Sherman on April 26th. President Davis fled south. On May 10th he was captured in Georgia, muffled in a lady's cloak and shawl, and became a prisoner at Fortress Monroe.

The war had called into military (land) service in the two armies together hardly fewer than 4,000,000 men; 2,750,000, in round numbers, on the Union side, and 1,250,000 on the other. The largest number of northern soldiers in actual service at anyone time was 1,000,516, on May 1, 1865, 650,000 of them being able for duty. The largest number of Confederate land forces in service at any time was 690,000, on January 1, 1863. The Union armies lost by death 304,369--44,238 of these being killed in battle, 49,205 dying of wounds. Over 26,000 are known to have died in Confederate prisons.