1860-1868 Chapter VII THE VIRGINIA CAMPAIGNS OF 1862--63

CHAPTER VII.

THE VIRGINIA CAMPAIGNS OF 1862-63

The Army of the Potomac lay inactive all through the winter of 1861-62. The country cried "Forward," but it was March before McClellan was ready to stir. Then he sailed down Chesapeake Bay to attack Richmond from the south, with Fortress Monroe as base. The splendidly disciplined and equipped army, 120,000 strong, began embarking March 17th.

Fortress Monroe lies at the apex of a wedge-shaped peninsula formed by the York and James Rivers, which converge as they flow toward the coast. April 4th, McClellan started on his march up this peninsula. A line of Confederate fortifications, twelve miles long, stretched across it, from Yorktown to the James, defended by 10,000 men. Yorktown must be taken to turn this line. A month was wasted in laborious siege preparations, for early in May, just before an overwhelming cannonade was to begin, the southern army evacuated the place and retreated toward Richmond.

General David D. Porter.

McClellan hurried after it. A desultory battle was fought all day on the 5th, near Williamsburg, the enemy withdrawing at night. McClellan now moved slowly up the peninsula, the last of May finding his army within ten miles of Richmond, encamped on both sides of the Chickahominy. By this time nearly 70,000 troops had gathered for the defence of the Confederate capital.

General Robert E. Lee.

May 31st, the Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston fell upon the part of McClellan's army south of the river, at Fair Oaks, and in a bloody battle drove it back a mile. McClellan sent re-enforcements across the river, and the retreat was stayed. The lost ground was regained next day, and the enemy driven into Richmond. Johnston having been wounded, General Robert E. Lee was now placed in command of the Army of Virginia, destined to lay it down only at the collapse of the Confederate government.

McClellan waited three weeks for better weather. He also expected McDowell's corps of 45,000, which had been kept near Fredericksburg to defend Washington, but was under orders at the proper time to cooperate with McClellan by moving against Richmond from the north. But Stonewall Jackson came raiding down the Shenandoah Valley, hustling General Banks before him. Washington was alarmed, and McDowell had to be retained.

Lee boldly took the offensive, and the "Seven Days' Fight" began. June 26th he attacked McClellan's extreme right under Porter, on the north side of the Chickahominy. He was repulsed, but Porter fell back farther down the river to Gaines's Mill, there fought all the next day against great odds, and was saved from total rout toward night only by the arrival of re-enforcements.

General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Jackson's army from the north had joined Lee's left, and McClellan's communication with York River was in danger. He decided to change his base to the James, where he would have placed it at first but for his expectation of McDowell and his desire to connect with him. Everything not transportable, including millions of rations and hundreds of tons of ammunition, had to be destroyed. Five thousand loaded wagons, 2,500 head of cattle, and the reserve artillery were then set in motion toward the James, protected by the army in flank and rear.

On discovering this movement Lee hastened to strike. A force was sent to assail the retreating column in the rear; but the bridgeless Chickahominy, guarded by artillery, held the pursuers at bay. Lee threw other portions of his army against McClellan's right, at Savage's Station on the 29th, at Frazier's Farm on the day following; but the Union troops each time stood their ground till ready and then continued their march.

July 1st found the retreating host concentrated on Malvern Hill, a plateau a mile and a half long and half as broad, with ravines toward the advancing enemy. Here McClellan planted seventy cannon, rising tier upon tier up the slope, seven heavy siege guns crowning the crest.

The position was impregnable, but Lee determined to attack. Shortly before sunset his men advanced boldly to the charge, but were mowed down by the terrible concentrated fire of the batteries. The hill swarmed with infantry as well, sheltered by fences and ravines, while shells from the gunboats in James River could reach every part of the Confederate line. Yet not till nine in the evening did Lee let the useless carnage cease. Badly demoralized as the opposing army was, McClellan at midnight withdrew to Harrison's Landing, farther down the James.

General J. E. B. Stuart's Raid upon Pope's Headquarters, August 22, 1862,

when Pope's despatch book fell into the hands of the Confederates.

During the Seven Days' Retreat he had lost 15,000 men; the Confederates somewhat more. Military authorities unite in pronouncing McClellan's change of base "brilliantly executed;" but the campaign as a whole was a failure, discouraging the country as much as Bull Run had done. McClellan prepared and fully expected to move on Richmond again from this new base, but early in August received orders to withdraw from the Peninsula. By the middle of the month the dejected Army of the Potomac was on its way north.

The last of June the Union forces in West Virginia, the Shenandoah Valley, and in front of Washington were consolidated into one army, and the same General Pope who had recently won laurels by the conquest of Island Number Ten, put in command. His headquarters, he announced, were to be in the saddle, and those who had criticised McClellan gave out that the Union army's days of retreating were past. McClellan was called from the Peninsula to strengthen this new movement.

Lee started north to crush Pope before McClellan should reach him. Pope had but 50,000 men against Lee's 80,000, and fell back across the Rappahannock. Lee sent Jackson on a far detour, via Thoroughfare Gap, to get into his rear and cut his communications. Jackson moved rapidly around to Manassas--one of the most brilliant exploits in all the war--and destroyed Pope's immense supply depot there. On August 29th he was attacked by Pope near the old battlefield of Bull Run. The first day's fight was indecisive, but Confederate re-enforcements under Longstreet arrived in time to join in the battle of the next. McClellan was in no hurry to re-enforce his rival, but proposed "to leave Pope to get out of his scrape as he might." Toward sunset in the battle of the 30th, Longstreet's column, doubling way around Jackson's right and Pope's left, made a grand charge, taking Pope straight in the flank.

General Thomas J. ("Stonewall") Jackson.

Porter's corps--the Fifth--part of McClellan's army, stood in the "bloody angle" of cross-fire. His loss was dreadful--2,000 out of 9,000. Pope was compelled to retire to Centreville. An engagement at Chantilly, September 1st, forced a further retreat to Washington. Pope resigned, and his army was merged in the Army of the Potomac, McClellan commanding all.

Lee now invaded Maryland with 60,000 men. Already the alarmed North heard him knocking at its gates. Hastily re-organizing the army, McClellan gave chase. Leaving a force to hold Turner's Gap in South Mountain, Lee pushed on toward Pennsylvania. By the battle of South Mountain, September 14th, Hooker got possession of the gap, and the Union army poured through. Seeing that he must fight, Lee took up a position on Antietam Creek, a few miles north of Harper's Ferry. Jackson had just received the surrender of the latter place, with 11,000 prisoners, and now hurried to join Lee.

By the night of September 16th, the two armies were in battle array on either side of the creek. To the rear of the Confederate left lay a cultivated area encircled by woods, a cornfield in its centre. At dawn on the 17th, Hooker opened the battle by a furious charge against the Confederate left, and tumbled the enemy out of the woods, across the cornfield, and into the thickets beyond, where he was fronted by Confederate reserves. The carnage was terrific. Re-enforcements under Mansfield were sent to Hooker, but driven back across the cornfield.

86 CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION

General Edwin V. Sumner.

Mansfield was killed and Hooker borne from the field wounded, Sumner coming up barely in time to prevent a rout. Once more the Confederates were pushed through the cornfield into the woods.

Here, crouching behind natural breastworks--limestone ridges waist-high--the southern ranks delivered so hot a fire as to repulse Sumner's men. Thus, all the morning and into the afternoon the tide of battle surged back and forth through the bloody cornfield, strewn with wounded and dead.

General Winfield S. Hancock.

On the Confederate right no action took place till late in the day. Burnside then attacked and gained some slight advantage. But re-enforcements from Harper's Ferry came up and were put in against him, forcing him back to the creek. During the next day McClellan feared to risk a battle. Being re-enforced, he intended to attack on the following morning; but Lee, who should have been crushed, having but 40,000 men to McClellan's 87,000, slipped away in the night and got safely across the Potomac. The Union loss was 12,400; that of the Confederates probably about the same.

The general dissatisfaction with McClellan's slowness caused his removal early in November, Burnside succeeding him. The new commander, who, as the head of the army, was an amiable failure, proposed to move directly against Richmond, but Lee flung himself in his path at Fredericksburg.

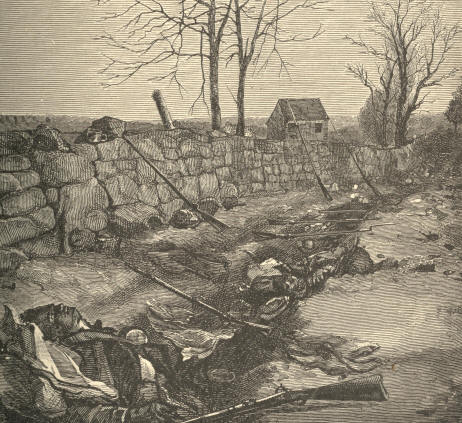

Fredericksburg lies on the south bank of the Rappahannock. Behind the city is a gradually ascending plain, bounded by heights which bend toward the river. Lee's army, 80,000 strong, lay in a semicircle along these heights, its wings touching the river above and below the town. Two rows of batteries, planted on the heights, swept the plain in front and flank. A sunken road, sheltered by a stone wall, ran along the base of the declivity. Burnside's army of 125,000 men occupied a range of hills on the north side of the river.

General Ambrose E. Burnside.

Lee's position was very strong; but the country was impatient for action, and Burnside too readily and without any definite plan gave the order to attack. December 11th and 12th were spent in crossing the river on pontoon bridges. The ominous 13th came. The first charge was made by 5,000 of Franklin's men against the Confederate right. The attacking column broke through the lines and reached the heights; but it was not supported, and Confederate reserves drove it back.

About noon an attack was made by Hancock's and French's corps against the Confederate left. They advanced over the plain in two lines, one behind the other. Suddenly the batteries in front, to left, to right, poured upon them a murderous fire. Great gaps were mowed in their ranks. Union batteries, replying from across the river, added horror to the din, but helped little. Still the lines swept on. They grew thinner and thinner, halted, broke, and fled.

Again they advanced, this time almost up to the stone wall. Behind it, hidden from sight, lay gray ranks four deep. Suddenly that silent wall burst into flame, and the advancing lines crumbled away more rapidly than before. Three times more the gallant fellows came on, bayonets fixed, to useless slaughter. That deadly wall could not be passed.

The Stone Wall at Fredericksburg.

The two wings having failed, the Union centre, under Fighting Joe Hooker, was ordered to try. He kept his batteries playing till sunset, hoping to make a breach. Four thousand men were then ordered into the jaws of death. Stripping off knapsacks and overcoats, and relying on the bayonet alone, they charged on the double-quick and with a cheer. They got within twenty yards of the stone wall. Again that sheet of flame! In fifteen minutes it was all over, and they returned as rapidly as they advanced, leaving nearly half their number dead and dying behind. During the day Burnside had had 113,000 men either across the river or ready to cross. Lee's force was 78,000.

Night put an end to the luckless carnage. Burnside's generals dissuaded him from renewing the attack next day, and the army re-crossed the river. They had lost 12,300 men; the Confederates 5,000. A writer to the London Times from Lee's headquarters called this December 13th a day "memorable to the historian of the Decline and Fall of the American Republic."

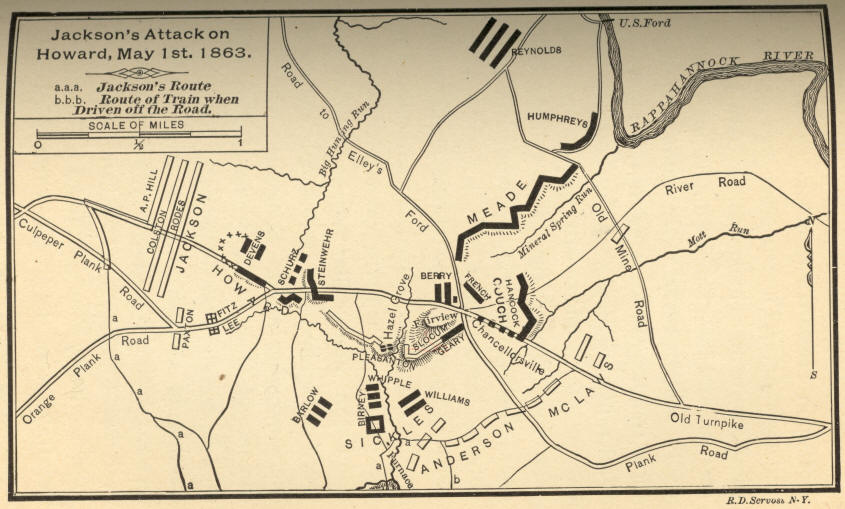

Burnside resigned in January, and Hooker took the command, but he did not assume the offensive till the last of April. Then, leaving three corps under Sedgwick to deceive Lee by a demonstration in front, he marched up-stream with the other four of his corps, crossed the Rappahannock and the Rapidan, partially turned Lee's left, and took up a position near Chancellorsville.

General Oliver O. Howard.

It was a perfect plan, and thus far triumphantly executed. But here Hooker waited, and the pause was fatal. On the night of April 30th Lee perceived that Sedgwick's movement was only a feint, and gathered all his forces, 62,000 strong, to fight at Chancellorsville. He fortified himself so firmly that Hooker with 64,000, or, including Sedgwick's two corps and the cavalry, 113,000, made not a single step of further advance.

General John Sedgwick.

R.D. Servoss, N.Y.

Jackson's Attack on Howard, May 1st, 1863.

Nor was this the worst. Hooker's right wing, under Howard, was weakly posted. On the 2d of May Stonewall Jackson, who cherished the theory that one man in an enemy's rear is worth ten in his front, making a detour of fifteen miles, got upon Howard's right unobserved, and rolled it up. The surprise was as complete as it was inexcusable. Arms were stacked and the men getting supper. Suddenly some startled deer came bounding into camp, gray-coats swarming from the woods hard behind. Almost at the first charge the whole corps broke and flee! But the victory cost the Confederates dear; Jackson was fatally wounded, probably by his own men.

All the next day the Union army fought on the defensive. Hooker was stunned in the course of it by a cannon-ball stroke upon the house-pillar against which he was leaning, and the army was left without a commanding mind. Sedgwick, who was to come up from below Fredericksburg and take Lee in the rear, found it impossible to do this in time, having to fight his way forward with great loss. When he drew near, Lee was enough at leisure to attend to him. Forty thousand troops, aching for the fray, were left idle while Lee was hammering away against the portion of the Union line commanded by Sickles. Ammunition gave out, and charge after charge had to be repulsed with the bayonet.

Sickles's brave men at last yielded. The Confederate attack of May 4th was nearly all directed against Sedgwick, whose noble corps narrowly escaped capture. That night the whole army fell back to nearly its old position north of the Rappahannock. Except that at Fredericksburg it was the most disgraceful fiasco on either side during the war. It cost 17,000 men, and accomplished less than nothing. The South was elated. It proposed again to invade the North and this time dictate terms of peace.

Early in June Lee's jubilant army, strengthened to 100,000, with 15,000 cavalry and 280 guns, started on its second grand Northern Campaign. It marched down the Shenandoah Valley, crossed the Potomac on the 25th, and headed for Chambersburg, Penn. The Army of the Potomac marched parallel with it, on the east side of the Blue Ridge, and crossed the Potomac a day later. Hooker suddenly resigned, and Meade was put in command.

General James Longstreet.

Lee reached Chambersburg; his advance even pushed well on toward Harrisburg, the capital of Pennsylvania. At Chambersburg he waited eagerly for those riots in northern cities by which the "copperheads" had expected to aid his march. In vain. Meade was drawing near.

"Pressed by the finger of destiny, the Confederate army went down to Gettysburg," and here the advance of both hosts met on July 1st. After some sharp fighting the Union van was driven back in confusion through Gettysburg, with a loss of 10,000 men, half of them prisoners. The brave General Reynolds, commanding the First Corps, lost his life in this action. The residue fell back to Cemetery Hill, south of the town. Meade, fifteen miles to the south, sent Hancock on to take command of the field, and see what it was best to do. This able and trusty officer hurried to the scene of action in an ambulance, studying maps as he went. He saw at a glance the strength of Cemetery Ridge and resolved to retreat no farther. The remaining corps were ordered up, and by noon of July 2d had mostly taken their positions.

The Union army lay along an elevation some three miles in length, resembling a fish-hook in shape. At the extreme southern end forming the head of the shank rose "Round Top," four hundred feet in height. Farther north was "Little Round Top," about three-fourths as high. Cemetery Ridge formed the rest of the shank. The hook curved to the east, with Culp's Hill for the barb. The Confederate army occupied Seminary Ridge a mile to the west, its left wing, however, bending around to the east through Gettysburg, the line being nearly parallel with Meade's, but much longer. Each army numbered not far from 80,000.

General George G. Meade.

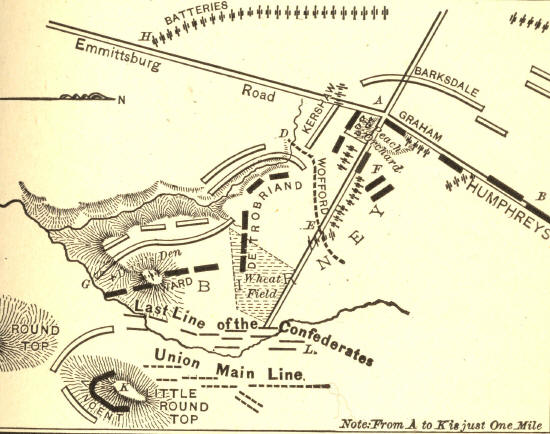

The battle of the second day began about three in the afternoon. Meade had neglected to occupy Little Round Top, which was the key to the Union line. Longstreet's men began climbing its rugged sides. Fortunately the movement was seen in time, and Union troops, after a most desperate conflict, seized and held the crest of the hill.

Along the Union left centre General Sickles's corps had taken a position in advance of the rest of the line, upon a ridge branching off from Cemetery Ridge at an acute angle. Here he was fiercely attacked and most of his force finally driven back into the line of Cemetery Ridge. The Union right had been greatly weakened to strengthen the centre. The Confederates charged here also, and carried the outer intrenchments at Culp's Hill. The Union losses during the afternoon were 10,000--three-fifths in Sickles's corps, which lost half its numbers.

The next morning was spent by Lee in preparing for a grand charge upon the Union centre, that of yesterday upon the left having failed, and the Confederates having this morning been driven from the ground gained the night before on the right at Culp's Hill. The storm burst about one o'clock. For two hours 120 guns on Seminary Ridge kept up a furious cannonade, to which Meade replied with 80. About three the Union cannon ceased firing. Lee mistakenly thought them silenced, and gave the word to charge.

An attacking column 18,000 strong, made up of fresh troops, the flower of Lee's men, and commanded by the impetuous Pickett, the Ney of the southern army, emerges from the woods on Seminary Ridge, and, drawn up in three lines, one behind the other, with a front of more than a mile, moves silently down the slope and across the valley toward the selected spot. Suddenly the Union batteries again open along the whole line. Great furrows are ploughed in the advancing ranks. They press steadily on, and climb the slope toward Meade's lines.

Note: From A to K is just one mile.

R.D. Servos N.Y.

Diagram of the Attack on Sickles and Sykes.

Two regiments behind rude intrenchments slightly in advance pour in such a murderous fire that the column swerves a little toward its left, exposing its flank. General Stannard and his lusty Vermonters make an irresistible charge upon this. Windrows of Pickett's poor fellows are mowed down by the combined artillery and musketry fire. A part of the column breaks and flees.

A part rushes on with desperate valor and reaches the low stone wall which serves for a Union breastwork. A venomous hand-to-hand fight ensues. Union re-enforcements swarm to the endangered point. The three Confederate brigade commanders are all killed or fatally wounded, whole regiments of their followers surrounded and taken prisoners. The rest are tumbled back, and the broken remnants of that noble column flee in wild confusion across the valley.

The Confederate loss on this eventful day was 16,000, the Union loss not one-fifth as great. General Hancock, whose command bore the brunt of the charge, was severely wounded. Meade should have pressed his advantage, but did not, and next day Lee retreated under cover of a storm and escaped across the Potomac. His losses during the three days had been frightful, amounting to 23,000. In one brigade, numbering 2,800 on July 1st, only 835 answered roll-call three days later. Meade's total losses were also 23,000. Meade had had on the field in all 83,000 men and 300 guns, Lee 69,000 and 250 guns.

Gettysburg marks the turning of the tide. The South's dream of getting a foothold in the North was forever past. She was soon to hear a gallant Northerner's voice demanding the surrender of Richmond.