1860-1868 Chapter VI THE WAR IN THE CENTRE

CHAPTER VI.

THE WAR IN THE CENTRE

We have seen that the fall of Donelson had driven the Confederates out of Kentucky. In the following September, 1862, Bragg invaded the State from Tennessee with 40,000 men. Buell hurried north from Nashville, and after an exciting race headed him off from Louisville. Bragg slowly fell back, first east, then south. Kentucky was rich in food and clothing, and his army plundered freely, coming out, it was boasted, with a wagon-train forty miles long. At Perryville Bragg turned upon Buell fiercely. An indecisive battle was fought, October 8, 1862, which gave the richly loaded wagon-train time to escape into Tennessee, whither Bragg followed.

The Christmas holidays of 1862 found the Confederate host at Murfreesboro, Tenn., thirty miles southeast of Nashville, where the Union army lay. Rosecrans, who had succeeded Buell, moved suddenly to the banks of Stone River, within four miles of the gay town, and prepared to attack. Bragg, like Wellington from Brussels on the morning of Waterloo, hurried forth to meet him. At dawn, December 31st, the gray-colored columns emerged from the fog that overhung the river, and spiritedly beat up the Union right. Two divisions were swept back. Sheridan's men, inspired by their dashing leader, held their ground for awhile, but fell rearward at last, and, forming a new line, stood at bay with fixed bayonets. Rosecrans recalled the troops who had crossed the river to make a similar attack upon the Confederate right, and massed all his forces at the point of assault. Six times the southrons charged, six times they were tumbled back by the Union batteries double-shotted with canister. Night fell on a drawn battle.

General William S. Rosecrans.

The next day, January 1, 1863, was peaceful save for cavalry skirmishing. January 2nd the awful combat was renewed. Rosecrans having planted artillery upon commanding ground, Bragg must either carry this or fall back. He attempted the first alternative, and was repulsed with terrible slaughter, losing 1,000 men in forty minutes. He escaped south under cover of a storm. In proportion to the numbers engaged, the battle of Stone River was one of the bloodiest in the war. About 45,000 fought on each side. The Union loss was 12,000, the Confederate nearly 15,000.

Rosecrans did not advance again till June, although Bragg lay quite near. The latter fell back as the Unionists approached, first into Chattanooga and then over the Georgia line. Rosecrans followed. Bragg was now re-enforced, and determined to retake Chattanooga, which lay on the Tennessee River and was an important strategical point. The two armies met on Chickamauga Creek, twelve miles south of Chattanooga. All through the first day's battle, September 19th, there was hot fighting--charges and countercharges--but no decisive advantage fell to either side. During the night Bragg was reenforced by Longstreet's corps from Virginia, and he opened the next day's fight with an assault upon the Union left. Brigades were moved from the centre to support the left. Through the gap thus made Longstreet poured his men in heavy columns, cutting the Union army in two. Its right wing became demoralized, and fled toward Chattanooga in wild confusion, Rosecrans after it at a gallop, believing that all was lost.

But all was not lost. General Thomas commanded the Union left. Like a flinty rock he stood while Polk's and Longstreet's troops surged in heavy masses against his front and flank. About three o'clock heavy columns were seen pouring through a gorge almost in Thomas's rear. They were Longstreet's men. It was a critical moment Granger's reserves came rushing upon the field. Raw recruits though they were, they dashed against Longstreet like veterans. In twenty minutes, at cost of frightful slaughter, the gorge and ridge were theirs. Longstreet made another assault, but was again repulsed. At nightfall Thomas fell back to Chattanooga, henceforth named, and justly, the "Rock of Chickamauga." For six hours he had held his own with 25,000 braves against twice that number. Out of 70,000 troops Bragg lost probably 20,000. Rosecrans's force was about 55,000, his loss 16,000.

Bragg proceeded to shut up the Union army in Chattanooga. Grant, now commanding the Department of the Mississippi, was ordered to recover Chattanooga, and his deeds along this front, though less often mentioned, will glitter upon the page of history with little if any less lustre than those about Vicksburg.

General George H. Thomas.

Upon his arrival, late in October, he found the city practically in a state of siege. Its railroad communication with Nashville was cut off, and supplies had to be hauled in wagons sixty miles over a rough mountain road. The men had been for some time on half rations. Thousands of horses and mules had starved, and the artillery could not be moved for lack of teams. There was not ammunition enough for one day's fighting. In five days Grant wrested the railroad from Bragg's men and bridged the Tennessee, so that an abundant supply of food and ammunition came pouring in.

Elated at his Chickamauga triumph, and unaware that he now had a greater than Rosecrans in his front, Bragg deemed it a safe and promising stratagem to despatch Longstreet's corps to Knoxville to capture Burnside. It was a fatal step, and Grant was not slow to take advantage of it. He telegraphed Sherman to put his entire force instantly en route from Vicksburg to Chattanooga.

Chattanooga lies on the south side of the Tennessee River, at the northern end of a valley running north and south. Along the eastern edge of the valley rises Missionary Ridge. On the western side and farther south, stands Lookout Mountain. After passing Chattanooga, the river turns and runs south till it laves the base of Lookout Mountain. The Confederate fortifications, twelve miles in length, ran along Missionary Ridge, across the southern end of the valley, and up over Lookout Mountain.

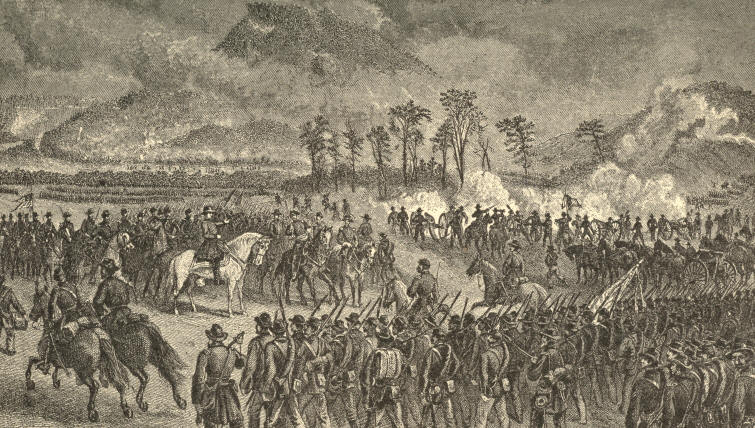

On November 23d, Thomas, who had succeeded Rosecrans, stormed the breastworks half a mile from the base of Missionary Ridge. The next day Grant sent "Fighting Joe Hooker" to sweep Bragg's detachment from Lookout Mountain. Mist lay along the lofty slopes as the gallant Hooker and his men moved up them, soon veiling the entire column from sight; and it was only by the rattle of the musketry that Grant knew how the fight progressed. This was the famous "Battle Above the Clouds." Hooker pounded the enemy so lustily that they were glad to evacuate the mountain in the night, and the next morning the Stars and Stripes saluted the breezes of its topmost peak.

General Joseph Hooker.

While Hooker had been thus engaged, and for some days before, Sherman had been at a movement that was even more momentous. He had slyly thrust his army up the Tennessee River above the city, placing it between the river and Missionary Ridge, and had worked its flank to the left as far as the mouth of Chickamauga Creek. He had thus gotten possession of the entire northeastern spur of that ridge with hardly the loss of a corporal's guard.

The morrow after this was accomplished, November 25, 1863, was a day of blood. Bragg's forces were now massed on Missionary Ridge, mainly in front of Thomas and Sherman. Hooker had come down into the valley and was to turn the enemy's left. If Bragg massed troops on either of the two wings, Thomas's braves were to be let slip against the weakened centre. Sherman got into action early in the morning, and fought his painfully difficult way slowly up the rugged acclivities in his front. Hooker had to bridge Chattanooga Creek, and did not attack till afternoon. By three o'clock Sherman was so hard pressed that Grant found it necessary to relieve him by sending Thomas forward at the centre.

The Battle of Lookout Mountain. (The "Battle Above the Clouds,'')

58

THE WAR IN THE CENTRE 59

The signal guns boom--one, two, three, four, five, six. Up spring Thomas's heroes from their breastworks, and rush like a whirlwind for the first line of Confederate rifle-pits. Bragg sees the advance and hurries help to oppose. His batteries open with shot and shell, then with canister. The infantry rake Thomas with a withering fire. Yet on, double quick, dash the lines of blue over the open plain, over rocks, stumps, and breastworks, bayonetting back or capturing their antagonists, till the first line of rifle-pits is theirs.

The orders had been to halt at this point and re-form. But here, with Bragg's artillery raining a veritable hell-fire upon them--here is no place of resting, and as the men's blood is up, they sweep forward unbidden, with a cheer. It is five hundred yards to the top--a steep ascent, covered with bowlders and fallen timber. Over the rocks, under and through the timber, each one scrambles on as he can. Half-way up is a line of small works. It is carried with a rush, and on the men go, right up to the crest of the ridge. Now they confront the heaviest breastworks. The air is thick with whizzing musket-balls, and fifty cannon belch flame and death. But nothing can stop that furious charge.

Sheridan's men reach the top first, the rest of the line close behind. The "Johnnies" are routed after a short fight, and the guns turned against them as they fly. By night Bragg's army is in full retreat, Chattanooga is safe and free, Grant's lines of communication are assured, and the keys of the State of Georgia in his hands.

General James B. McPherson.

The Union forces in this battle numbered about 60,000, the Confederate half as many; but the latter fought with all the advantage which the mountain and breastworks could give them. They lost nearly 10,000 including 6,500 prisoners. The Union loss was between 5,000 and 6,000--2,200 in the one hour's charge against the centre.

There was no halting, no resting. Scarcely had the sounds of yesterday's cannonade died away, when Sherman's already jaded forces were put in motion to the north, to make sure that Burnside was set free at Knoxville; but Longstreet had already raised the siege and started east. By December 6th, Bragg's redoubtable army, which, so recently as September, swore to reconquer Tennessee and to invade Kentucky, was rent in twain, one part of it fleeing to Virginia, the other to the heart of Georgia.

No important military movement occurred in the Centre during this winter of 1863-64. In March Grant was made Lieutenant-General, with command of all the Union armies, Sherman succeeding to the headship of the Mississippi Department.

62 CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION

The latter accompanied his superior toward Washington as far as Cincinnati, and there, in a parlor of the Burnet House, the two victorious generals, bending over their maps together, planned in outline that gigantic campaign of 1864-65, which was to end the war; then, grasping one another warmly by the hand, they parted, one starting east, the other south, each to strike at the appointed time his half of the ponderous death-blow.

Sherman pushed out from Chattanooga May 6, 1864, with 100,000 men and 254 cannon. His force comprised the Army of the Cumberland, 60,000, under Thomas; the Army of the Tennessee, 25,000, under Schofield; and the Army of the Ohio, 15,000, under McPherson. Johnston, who had superseded Bragg, lay behind strong works at Dalton, a few miles southeast, with 64,000 men, his base being Atlanta, 80 miles away. Sherman's supplies all came over a single line of railroad from Nashville, nearly 150 miles from Chattanooga as the road ran. Every advantage but numbers was on Johnston's side.

Sherman calculated that the Army of the Cumberland could hold his opponent at bay, while the two smaller armies crept around his flanks. This plan was adhered to throughout, and with wonderful success. All through May and the first of June a series of skilful flanking movements compelled Johnston to fall back from one position to another, each commander, like a tried boxer, constantly on the watch to catch his opponent off guard. Heavy skirmishing day after day made the march practically one long battle.

June 10th Johnston planted his army upon three elevations--Kenesaw, Pine, and Lost Mountains--and stubbornly stood at bay. A pouring rain, which turned the whole country into a quagmire and the streams into formidable rivers, made the usual flank manoeuvre impracticable. Sherman resolved to assault in front. June 27th a determined onset was made along the whole line for two hours but failed, though the troops gained positions close to the hostile works and intrenched. They lost 2,500; the Confederates not more than a third of this number. The roads having now improved, Sherman resorted to his old tactics, the Confederates having to fall back across the Chattahoochee, and come to bay under the very guns of Atlanta.

Just at the critical moment, when Sherman's army was slowly closing in around Atlanta, General Johnston, so wary and cool, was superseded by the young and fiery Hood, pledged to assume the offensive. On the 20th Hood made a furious attack on Hooker's front, but was repulsed with heavy losses. On the 22d he struck again, and harder. By a night march, Hardee's corps at dawn fell upon the Union left flank and rear like a thunderbolt out of a clear sky, rolling up the Army of the Tennessee in great confusion. The brave and talented McPherson was killed early in the action, Logan succeeding. "McPherson and revenge," he cried, as upon his coal-black steed he careered from post to post of danger, inspiring his men and restoring order. The veterans soon recovered from their surprise. The Union lines were completely re-established, and by night Hood's army was driven back into the city, having sacrificed probably 10,000 much-needed men, 2,500 of them killed.

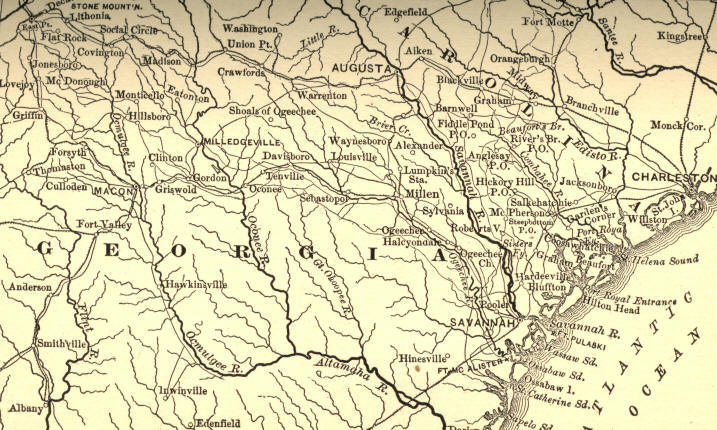

Atlanta to Savannah.

Sherman now began to swing round to the south and southeast of Atlanta, till at last he cut its communications with the Confederacy. Hood evacuated the city and his opponent entered it, September 5th. The northern troops, after their four months' incessant marching and fighting, now got a little well-earned rest. Their total losses from Chattanooga were 32,000. The Confederates had sacrificed about 35,000--the larger part under Hood.

The last of September Hood struck out boldly for Tennessee, menacing, and, in fact, temporarily rupturing Sherman's long supply-line from Nashville. Leaving one corps to hold Atlanta, Sherman raced back for 100 miles in pursuit. The railroad being well guarded, Hood could do no serious damage, and finally turned west into Alabama. Sherman now resolved on a march to the sea.

Thomas, with three corps, was sent to Tennessee to look out for Hood. The 62,000 troops remaining at Atlanta were put into light marching trim, and the wagons filled with 20 days' rations and 200 rounds of ammunition per man. All storehouses and other property useful to the enemy were then destroyed, communications with the North cut, and November 15th a splendid army of hardy veterans swung off for the Atlantic or the Gulf, over 200 miles away. Their orders were to live on the country, the rations being kept for emergencies; but no dwellings were to be entered, and no houses or mills destroyed if the army was unmolested. The dwelling-house prescription was, alas, too often broken over. There was little resistance, Georgia having been drained of its able-bodied whites. Negroes flocked, singly and by families, to join "Massa Linkum's boys." The railroads were destroyed, and the Carolinas thus cut off from the Gulf States.

Each regiment detailed a certain number of foragers. These, starting off in the morning empty-handed and on foot, would return at night riding or driving beasts laden with spoils. "Here would be a silver-mounted family carriage drawn by a jackass and a cow, loaded inside and out with everything the country produced, vegetable and animal, dead and alive. There would be an ox-cart, similarly loaded, and drawn by a nondescript tandem team equally incongruous. Perched upon the top would be a ragged forager, rigged out in a fur hat of a fashion worn by dandies of a century ago, or a dress-coat which had done service at stylish balls of a former generation. The jibes and jeers, the fun and the practical jokes, ran down the whole line as the cortege came in, and no masquerade in carnival could compare with it for original humor and rollicking enjoyment. ... The camps in the open pine-woods, the bonfires along the railways, the occasional sham battles at night with blazing pine-knots for weapons whirling in the darkness, all combined to leave upon the minds of officers and men the impression of a vast holiday frolic." [footnote: The March to the Sea, by Major-General J. D. Cox. Campaigns of the Civil War. Scribners.]

At the start Sherman was uncertain just where he should strike the coast. The blockade vessels were asked to be on the lookout for him from Mobile to Charleston. By the middle of December the army lay before Savannah. Hardee held the city with 16,000 men, but evacuated it December 20, 1864, Sherman entering next day. He wrote to Lincoln, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah." The capture of Fort McAllister a week before had opened the Ogeechee River, and Sherman now established a new base of supplies on the sea-coast.

The North rang with praises of the Great March, which had pierced like a knife the vitals of the Confederacy. Georgia, with her arsenals and factories, had been the Confederacy's workshop. Twenty thousand bales of cotton had been burned upon the march, besides a great amount of military stores. The 320 miles of railroad destroyed had practically isolated Virginia from the South and the West. And all this had been done with the loss of less than 1,000 men.

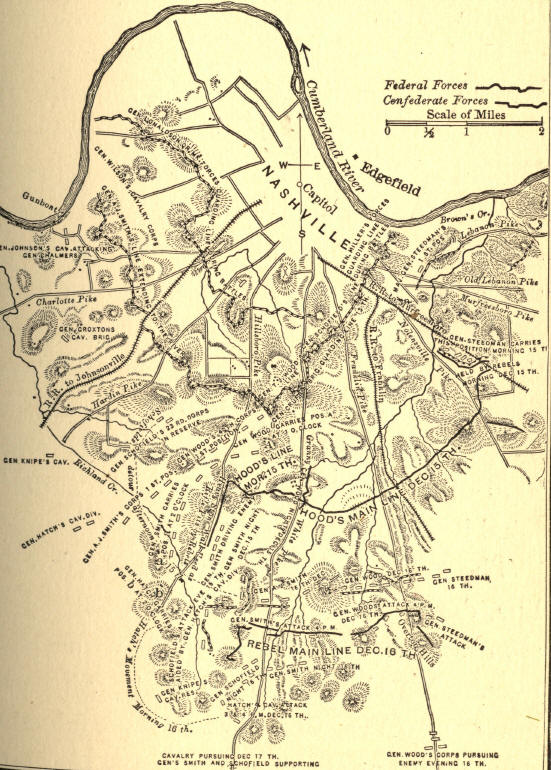

Meanwhile Thomas had dealt the Confederacy another staggering blow. The adventurous Hood had advanced with his army of 44,000 to the very gates of Nashville. The deliberate Thomas, spite of prickings from Grant, waited till he felt prepared. Then he struck with a Titan's hand. The first day's fight, December 15th, drove the Confederate line back two miles. Hood formed again on hills running east and west, and hastily fortified. All next day the battle raged. Late in the afternoon the works on the Confederate left were carried by a gallant charge. Total rout of Hood's brave army followed. It fled south, demoralized and scattered, never to appear again as an organized force. In the two days' battle, 4,500 prisoners and 53 guns were taken.

The Battle-Field of Nashville.

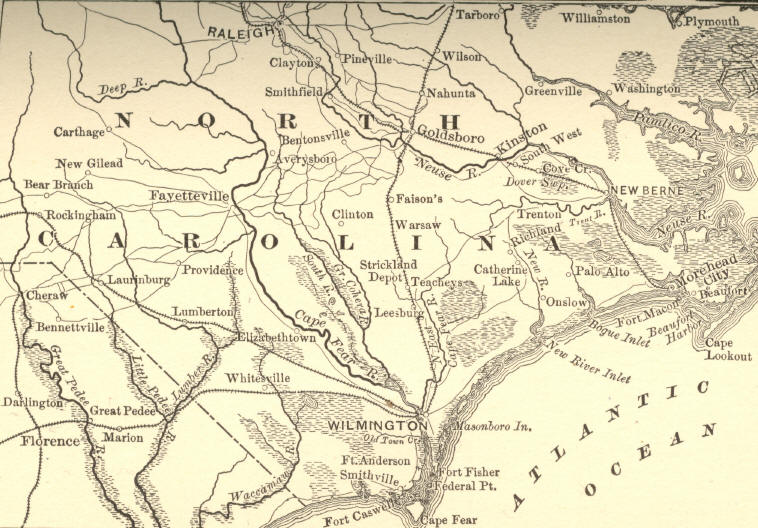

February 1, 1865, his troops all rested and equipped afresh, Sherman set his face to the north. The days of frolic were over. Continuous rains had made the Carolinas almost impassable. The march now begun was an incessant struggle with mud, swamps, and swollen rivers. A pontoon and trestle bridge three miles long was thrown across the Savannah, and miles of corduroy road were built through continuous swamps. Charleston, incessantly besieged since the war opened, where the United States had wasted more powder and iron than at all other points together, fell without a blow. Columbia was reached the middle of the month. It caught fire--just how has never been settled--and the greater part of the city was destroyed. Sherman's men helped to put out the flames, and left behind provisions and a herd of five hundred cattle for the suffering inhabitants.

Map of North Carolina.

The army pushed on toward North Carolina, destroying railroads as it went. Johnston was athwart their path with 30,000 men. March 16th he struck Sherman's army at Averysboro', N. C., and three days later at Bentonville. In the latter battle he was completely routed, and re treated during the night. Sherman swept on to Goldsboro', where re-enforcements from the coast, under Schofield, increased his army to 90,000. He was undisputed master of the Carolinas. By this time the Confederacy was hastening to its fall. April 11th the news of Lee's surrender was hailed in Sherman's army with shouts of joy. A few days later Johnston surrendered to the hero of Atlanta and of the March to the Sea.